Related Articles

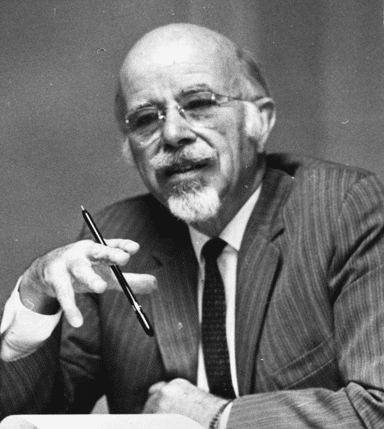

Celebrating Donald A. McGavran: A Life and Legacy

McGavran was a prolific writer of letters, articles, and books, as well as a world traveler. No one, to my knowledge, has visited as many mission fields, conducted as many interviews, or researched the growth and decline of Christian churches as widely as McGavran. He influenced mission theory and practice internationally and the movement he started continues to move forward, empowered by appreciative followers.

Willow Creek or Lima? Europe’s Church Planters Ask

Europe’s church planters, for the most part frustrated (except for some notable exceptions among the Pentecostals), are looking for clues to the future in such diverse places as Willow Creek in suburban Chicago and in Lima, Peru.

Welcoming the Stranger

Presenter: Matthew Soerens, US Director of Church Mobilization, World Relief Description: Refugee and immigration issues have dominated headlines globally recently. While many American Christians view these…

The Roles of Church and Mission in Crisis Management: Overlap? Competition? Cooperation?

Description: This webinar will look at the issues churches and missions face in responding to crises on the field. How do they cooperate and communicate…

What Mcgavran’s Church Growth Thesis Means

0ne of the most provocative and stimulating attempts in recent years at appraising present-day missionary methods is that by Dr. Donald Anderson McGavran, former missionary to India and now dean of the new Fuller School of World Mission and Institute of Church Growth, Pasadena, Calif.