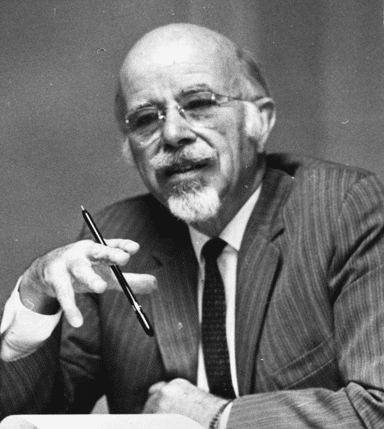

Celebrating Donald A. McGavran: A Life and Legacy

by Gary L. McIntosh

McGavran was a prolific writer of letters, articles, and books, as well as a world traveler. No one, to my knowledge, has visited as many mission fields, conducted as many interviews, or researched the growth and decline of Christian churches as widely as McGavran. He influenced mission theory and practice internationally and the movement he started continues to move forward, empowered by appreciative followers.

Imagine for a moment that you have received an invitation to attend a meeting that is to be held in January 1985 in the office of the dean emeritus of the School of World Mission at Fuller School of Theology. Several other people have also received invitations. In attendance with you will be the following: a foremost educator with a PhD in education from a highly-respected university, an evangelist who personally led over one thousand people to faith in Christ, a church planter who established fifteen churches in the span of seventeen years, a linguist who translated the Gospels into a new dialect, an administrator who directed the work of a mission agency in one of the world’s largest countries, a world-renowned mission strategist, and a well-known author whose books and articles have changed the course of his discipline.

Of course, you accept the invitation, and after traveling to Pasadena, you make your way to the campus. After introducing yourself to the secretary in the School of World Mission, she leads you into the office of the dean emeritus. However, once inside, you are surprised to find there are only two people attending the meeting—yourself and Donald McGavran. It suddenly dawns on you that the educator, evangelist, church planter, linguist, administrator, mission strategist, and author are all the same person—McGavran, the premier missiologist of the twentieth century.

McGavran was a prolific writer of letters, articles, and books, as well as a world traveler. No one, to my knowledge, has visited as many mission fields, conducted as many interviews, or researched the growth and decline of Christian churches as widely as McGavran. He influenced mission theory and practice internationally and the movement he started continues to move forward, empowered by appreciative followers.

Unfortunately, during the twenty-five years since his death in 1990, McGavran has almost disappeared from the writings of some missiologists. Even those who do have an awareness of him often discount the impact he once had (and continues to exert) on church life and ministry. No doubt part of the reason for this relates to the fact that his last published book, The Satnami Story, was released twenty-five years ago.

Without publications, it is easy to be forgotten. It is the proverbial “out of sight, out of mind” scenario. However, it is curious that a good number of today’s researchers ignore McGavran’s work. Below I present a brief overview of his life and a reminder of his ongoing legacy.

Brief History

Mission was the natural expression of Donald McGavran’s heritage. His story cannot be separated from that of the generations of faithful Christians and missionaries who came before him. James and Agnes Anderson, McGavran’s maternal grandparents, went to India in 1854 as missionaries with the Baptist Missionary Society. His father journeyed there in 1891 as a missionary with the Foreign Christian Missionary Society, and the two families—Andersons and McGavrans—were united in 1895 when John married the Anderson’s daughter, Helen.

In 1923, Donald and Mary McGavran also went to India and served there until 1954. Counted all together, the three generations of Anderson and McGavran families—grandparents, parents, children, aunts, uncles, and cousins—committed a total of 362 years to missionary work in India.

Donald Anderson McGavran was born on December 15, 1897, in Damoh, India. He was homeschooled for most of his early education, while his father worked as an evangelist and supervised an orphanage for boys. In 1910, the family returned to the United States for a furlough, but it turned into an extended stay so the McGavran children (Grace, Donald, Edward, and Joyce) could complete their secondary education.

McGavran attended junior high school in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and Tulsa, Oklahoma, then high school in Indianapolis, Indiana, graduating in 1915. He enrolled at Butler College that fall, but his college years were interrupted by service in World War I. Following a brief time in France, he returned to Butler and graduated in 1920. Two years later, he received a BD in Christian education from Yale Divinity School (1922) and married his college sweetheart, Mary Howard on August 9, 1922. The couple took classes at the College of Missions in Indianapolis, with McGavran receiving a MA degree (1923).

Donald and Mary McGavran sailed for India in November 1923. Beyond them lay a future that was unimaginable at the time—the tragedy of a child’s death, the pain of rejected leadership resulting in a demotion, the strain of struggle to evangelize a low-caste tribe, and the loss of a dream to train leaders on how to see greater growth in the Church. Yet as God would script it, the ministry of McGavran was destined to be one of the twentieth century’s glittering triumphs.

A Missionary in India

From 1923 until 1932 McGavran worked as director of religious education for the United Christian Missionary Society (UCMS). His primary job was to oversee and improve the teaching in the mission schools. Then, following a furlough where he completed work for a PhD in education at Columbia University (graduated 1936), McGavran was elected secretary-treasurer of his Indian Mission (1932-1935).

It was during this time that he was introduced to the work of Methodist Bishop Waskom Pickett and became interested in the growth of churches, especially the mass movement phenomena. He worked with Pickett on a study of churches in mid-India. The study found that the group movement approach to evangelism produced healthy church growth since it encouraged groups of families to come to salvation without social dislocation. The study called for a redirection of mission energies and was published in 1938 as Christian Mission in Mid India: A Study of Nine Areas with Special Reference to Mass Movements.

However, McGavran’s fellow missionaries refused to employ some of the new insights that were discovered, and when his term as secretary was up, he was not reelected. Instead, he was appointed as an evangelist among the low-caste Satnami people (1935-1954).

During the remainder of his missionary years, he worked among the Satnamis trying to start a people movement. He was fruitful in winning around one thousand persons to faith in Christ, and planted fifteen small churches, but a people movement never developed. However, the years of evangelism and church planting produced numerous insights regarding effective evangelism, which were published in The Bridges of God (McGavran 1955). Reviews of the book lauded McGavrans’s courageous thinking. No one knew it at the time, but the Bridges of God was destined to change the way missions was practiced around the globe and it became the Magna Carta of the Church Growth Movement (CGM), the primary document from which the movement grew.

A World Traveler

When the McGavrans returned to the United States in 1954, they fully intended to return to India when their furlough was over. The leaders of the UCMS recognized, however, that McGavran was a world expert on mission practice and theory and felt that sending him back to his old mission work in India was not the best move.

Providentially, the UCMS decided to send McGavran on several tours of Puerto Rico, Formosa, Philippines, Thailand, Congo, and India to study the growth of the church in those lands. Those studies, and many to follow, provided the data and background for a number of books, articles, and reports that he would write over the coming decade. From 1955 through 1960, he was also engaged as a peripatetic professor of missions, where he rotated among Butler University (Indianapolis, Indiana), Phillips University (Enid, Oklahoma), Drake University (Des Moines, Iowa), and Lexington College of the Bible (Lexington, Kentucky) teaching future missionaries.

A Dean of Missiology

The years of travel and teaching provided a laboratory for the study of church growth throughout the world, and McGavran began to envision the starting of a graduate Institute of Church Growth. After receiving rejections from several seminaries, he was invited to start an Institute for Church Growth at Northwest Christian College in Eugene, Oregon, and the new institute opened on January 1, 1961.

During the next four years, fifty-seven students—primarily mid-career missionaries—studied the new science of church growth. The years provided time to develop curriculum, develop reading lists, and publish studies of growing churches. However, as 1965 began, the board of Northwest Christian College determined that it was financially unable to continue supporting the Institute and it looked like it was going to close.

God had other plans, and in the spring of 1965 Fuller School of Theology asked McGavran to move the Institute for Church Growth to Pasadena and become the founding dean of the School of World Mission. Thus, at age 67, McGavran took on what was to become his most well-known work—the founding of an influential school of missiology. He brought together some of the most influential researchers and writers on mission theory at that time—Alan Tippett, Ralph Winter, Charles Kraft, C. Peter Wagner, and Arthur Glasser. Together, they changed the face of mission strategy during the last part of the twentieth century.

Understanding Church Growth (McGavran 1971) attained wide attention. It established Church Growth Theory as an orderly, systematic science. The book answered the question How is carrying out the will of God to be measured? It was broken into five major sections: theological considerations, growth barriers, growth principles, understanding social structure, and establishing bold goals. The book presented McGavran’s missional theories (e.g., receptivity, people groups, homogeneity, discovering the facts of growth or decline, setting bold goals, and understanding social structure).

However, it was at the Lausanne Congress on Evangelism that the CGM came of age. Some 2,700 participants from about 150 nations gathered in Lausanne, Switzerland, for the Congress on Evangelism in July 1974. Approximately 512 attendees were from the United States, and the Fuller faculty played key roles in gathering data, as well as presenting papers and leading sessions.

Tippet, Winter, and McGavran presented plenary papers, and Wagner led a four-day workshop on church growth. The great success of church growth at Lausanne was due in part to the numerous missionaries who had been trained at the School of World Mission. Over one hundred of the attendees at Lausanne were Fuller alumni. This, along with the fact that McGavran and other faculty members had input into the design of the Lausanne agenda, put church growth on the map internationally.

Final Years

McGavran retired from the deanship of the School of World Mission in 1971, but he continued to teach part time until 1985. In those years, he collaborated with Glasser on Contemporary Theologies of Mission (Glasser and McGavran 1983). This 250-page book focused on the most controversial missiological questions of the 1980s. Perhaps his major accomplishment was the publication of Momentous Decisions in Missions Today (McGavran 1984). Speaking from the vantage point of more than a half century of personal involvement in missions, he addressed the major questions of the 1980s under four headings: theological, strategical, organizational, and methodological. He reaffirmed the primacy of gospel proclamation, conversion, and church planting. More importantly, he focused on the importance of the cities and urban evangelism.

McGavran passed away on July 10, 1990, at the age of 92. Kent Hunter, editor of Global Church Growth, wrote in “So Ends a Chapter of History”:

With the death of Dr. Donald McGavran, an entire chapter of Christian history comes to a close. His life, work, writings, teachings, and his influence on countless thousands of Christians throughout the world represents a unique era.

Throughout history, God raises up Christian leaders who have a specific task and direction. When they are gone, their movements often continue. Their influence is not buried with their mortal remains. Their vision continues to spark generations who follow. Their presence, unique as it is, is gone from this earth forever. There will not be another McGavran. Not now—not ever. An epoch represented in the life and work of our dear friend and “comrade in the bonds of the Great Commission” (as he so often signed his letters) comes to a close. (Hunter 1990)

Legacy

By the time of McGavran’s death, the CGM was widely accepted and highly influential in informing mission theory and practice around the world. However, during the 1990s the movement began to wane. No doubt a number of factors led to a reduced visibility, such as the modern hunger for the next new thing. Yet McGavran’s own death was a major contributing factor, as the movement lost its primary promoter and apologist with his passing. Yet, even with the reduced public acceptance of Church Growth Theory, McGavran’s insights continue to impact missionary strategy and practice today. The following are just a few aspects of his continuing legacy

1. While the study of mission had been around for some time, McGavran gathered the faculty at Fuller Theological Seminary who significantly developed the field of missiology for American evangelicals. The founding of the School of World Mission provided for the development of a missiological curriculum that informed the basic core curriculum of missiological studies at many American evangelical institutions for the remainder of the twentieth century. He coined and defined many missiological terms and established a significant part of the agenda for twentieth-century American evangelical missiology.

2. McGavran observed that Western missionaries who came primarily from individualist cultural backgrounds regarded one-by-one decisions for Christ as the only acceptable method. Yet in most of the world, group (collectivist) decisions were preferred. This led him to see the need for including anthropology and sociology as components of missionary training to study social structure. His first faculty hire was Alan Tippet, who had a PhD in anthropology. Even though the conservative evangelical branch of the Church viewed anthropology and sociology with critical eyes, McGavran saw their importance and included them as key aspects of his Church Growth Thought.

3. McGavran stressed a return to Great Commission mission and compelled Christians to recognize that the day of mission was not dead. He brought back the revolutionary idea that churches ought to be growing (i.e., making disciples) rather than remaining static. He promoted the classical understanding of mission as being the proclamation of the gospel of salvation and the planting of churches, and spoke of this so often that critics often complained that he had only one string on his violin. But this was part of his genius. A leader must have a clear and simple message that can be understood and embraced by the constituency he or she is trying to lead. Great leaders must keep saying the same thing over and over again, which is precisely what McGavran did throughout his life.

4. McGavran recognized the demise of colonial missions and pointed the way to the post-colonial era, which called for new contours of missionary practice. He challenged the mission station approach that was pleased with slow growth, and promoted a people movement approach, which looked for a greater harvest. By doing so, he provided a positive voice for missions when voices were saying God was dead, the day of missions was over, and that missionaries should go home. His positive perspective continues to be heard in many corners of the missionary world today.

5. In a time when most church leaders thought people came to Christ primarily through mass events, church revivals, camp meetings, home visitation, and cold calling, McGavran discovered that the main bridges to Christ were family and friends. The idea of household evangelism was not new (it is found throughout the Bible), but McGavran demonstrated the fruitfulness of this approach through research. By doing so, he set fire to a new movement of evangelism. Whether labeled friendship evangelism, lifestyle evangelism, web evangelism, network evangelism, or oikos (household) evangelism, each owes much to his initial research.

6. McGavran highlighted the fact that receptivity to the gospel rises and falls among different peoples in different circumstances and in different times. He argued that peoples’ openness to the gospel should control the direction of resources (i.e., receptive people receive greater resources, while less receptive ones receive fewer resources). Although everyone does not agree with this principle, it is a common part of evangelistic practice today and guides deployment of personnel and expenditure of budgets (e.g., church planting is most often focused on receptive populations).

7. McGavran’s continuing influence is observed in numerous other themes that continue to impact the decision-making of church and mission leaders. For example, (1) the importance of assimilating newcomers into the social networks of a local church, (2) the necessity of making disciples rather than just getting decisions, (3) the need to multiply disciples and churches in all ta ethne (the nations), (4) the significance of understanding context, and (5) the requirement of planting indigenous churches.

Donald McGavran’s legacy lives on. His insights, perspectives, and approaches continue to inform mission theory and practice across numerous cultures and in most countries of the world. Whether the Church Growth Movement will continue, I do not know. However, it is likely that McGavran’s principles of church growth will continue to influence mission theory and practice for the foreseeable future.

References

Glasser, Arthur and Donald A. McGavran. 1983. Contemporary Theologies of Mission. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books.

Hunter, Kent. 1990. “So Ends a Chapter of History.” Global Church Growth, July-September.

McGavran, Donald A. 1990. The Satnami Story. Pasadena, Calif.: William Carey Library.

_____. 1984. Momentous Decisions in Missions Today. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books.

_____. 1974. “A New Age in Missions Begins.” Church Growth Bulletin, November.

_____, ed. 1972. Eye of the Storm: The Great Debate in Mission. Waco, Tex.: Word Books.

_____. 1972. Crucial Issues in Missions Today. Chicago: Moody Press.

_____. 1970. Understanding Church Growth. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

_____. 1955. The Bridges of God. New York: Friendship Press.

….

Gary L. McIntosh is a speaker, author, and professor of Christian ministry & leadership at Talbot School of Theology, Biola University. His forthcoming book, Donald A McGavran: A Biography of the Twentieth Century’s Premiere Missiologist, was recently released.

EMQ Oct 2015, Vol. 51, No. 4 pp. 424-431. Copyright © 2015 Billy Graham Center for Evangelism. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission from EMQ editors. For Reprint Permissions beyond personal use visit our STORE (here).