Puck and the Mischief of Measurement: How to Assess Ministry Outcomes

by Daniel Rickett and Bob Morrison

The danger is that easily measured outcomes will be measured while others remain unmeasured, leading to misallocated resources and superficial benefits.

Measurement has long been the hobgoblin of humanitarian assistance. What makes us think it’s good for evangelical missions? Puck, as you may recall, is the mischievous sprite in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Thanks to Puck, a lover’s affections are misdirected, and so begins a series of antics to fix the mistake.

Measuring ministry outcomes can be like that. Both the attempt at measurement and the lack of it invite mischief. How do you know, for instance, that a person is taking steps toward faith? For that matter, how do you know a person has trusted Christ and experienced salvation? It’s a little easier to determine that, say, a person has experienced better health because of your effort. Then again, how do you know your effort made the difference and not other factors? The problem gets worse when you try to assess change on a social level. How do you know your HIV/AIDS prevention program is actually reducing the AIDS pandemic? How do you know your anti-trafficking program is making a difference? Some outcomes are tangible (e.g., better health, improved skills, and increased income) and lend themselves to measurement. Other outcomes are intangible (e.g., faith, hope, and love) and elude empirical measurement. The danger is that easily measured outcomes will be measured while others remain unmeasured, leading to misallocated resources and superficial benefits.

What Is Measurement?

Measurement is a way of seeing. It’s assessing whether or not we have helped others as intended. In its simplest form, measurement compares two points. The difference between the points indicates whether our effort is achieving its purpose or not. The points of comparison may picture the past and the present, or the present and an ideal state. Either way, measures are meaningful only if expectations are clear from the start. Measurements can be made quantitatively or qualitatively. Quantitative measures answer questions such as “How many?” and “What percent?” For instance, if the objective is to reduce the incidence of waterborne diseases, then the measure would count the incidence rate both before and after the intervention. Qualitative measures describe characteristics of a person(s) or situation. They are useful in measuring less tangible outcomes, such as the successful rehabilitation of a trauma victim. In this case, the qualitative change in the person’s outlook (positive) and desire to restart his or her life evidences progress toward the goal of recovery. Effective measures answer the question “Have we successfully helped the person(s) as intended?”

Why Measure?

Although humanitarian assistance has a long history of measurement, it has not been a priority among evangelical missions until recently. As happened in the arena of foreign aid, the push to measure outcomes has come from funders (such as foundations and major donors), and that at a time when the whole philanthropy world is under mounting scrutiny. As noted in a December 2007 headline in The Wall Street Journal, funders are lining up to say “how charities can make themselves more open.” Both charities and foundations are being held to rising standards of accountability and transparency.

In this environment of scrutiny, outcomes-based evaluation (also referred to as results-based evaluation) has become the new language of accountability, and its essential tool is measurement (see USAID EVALWEB; Kusek and Rist). In general, outcomes-based evaluation means measuring performance against objectives. While accountability and transparency are widely endorsed by evangelical missions, outcomes-based evaluation is not. Laying aside the practical difficulties of achieving meaningful social change—a feat even governments and the United Nations have botched (see Easterly 2006; Dichter 2003)—no serious evangelical is going to claim he or she has the yardstick for measuring the intangible effects of the gospel.

The issue is not merely pragmatic. It’s a theological question: what does the Bible say about results in the work of the gospel? We first raised this question five years ago in a symposium with the theme, “Toward a Biblical View of Results,” hosted by Geneva Global in Wayne, Pennsylvania. Since then, we know of no further discussion in a theological vein. Bible scholars would do a great service by working with mission leaders to establish a biblical frame of reference for the stewardship of results in Christian ministry. These challenges notwithstanding, it’s easy to find good reasons to measure outcomes. Here are three:

1. To keep faith with a vision. For starters, it’s difficult to keep faith with a vision without measurement. You must have a means of gauging whether your effort is achieving its purpose. Any effort, even the most informal, to understand where you are in relation to where you want to be, involves measurement. Measurement is integral to pursuing a vision.

2. To learn from what we do. The process of measuring outcomes naturally leads to discussions about what we value, what we envision, and what constitutes meaningful results. For example, learning occurs when we find that the approach we have been using, an approach that made sense in the past, is no longer effective. Measuring creates the opportunity to review our approach, determine what is not working, reinterpret the situation, and adopt a new approach.

3. To account for what we do. Donors want more than reports on activities and how money was disbursed. They want to know if their contributions have made a difference. We are obliged to show them that what we are attempting to achieve is being or has been achieved, and, if not, why. If we claim we will change lives in some way, then we must be able to do it, and we must be able to show that we can do it. If it can’t be done as we had originally thought, which is often true, donors need to know that too.

The Outcomes-based Approach to Measurement

While there are several ways to measure a ministry’s impact, the outcomes-based approach is the most common. It also happens to be the most suitable method of accountability to multiple layers of stakeholders (i.e., beneficiaries, service providers, donors, and the public). Three elements comprise a measurement: people (who), outcomes (what), and time (when). These elements need periodic adjustment lest they degenerate into irrelevant obligations or, as Puck would attest, misdirected affections.

1. People. The first element of measurement is a specific population in a specific place. Let’s take the example of a skills-training and microfinance program in northern India, with a program objective to reduce the economic vulnerability of poor immigrants. Defining the focus population—through clear income, education, and wealth criteria—is critical to prevent any who are better off from receiving services intended for those living in greater poverty.

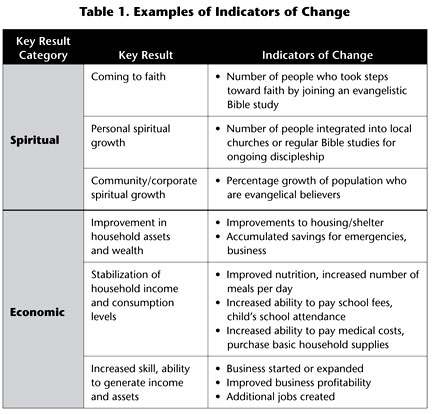

2. Outcomes. Identifying outcomes—the tangible and the not-so-tangible—is a two-step process. First, it’s necessary to define the desired key results and the indicators of change for each key result. Key results are the general areas in which you want people’s lives improved (e.g., people take steps toward faith, believe in Jesus, experience better health, benefit from increased wealth). Key results do not cover everything the project will accomplish. They identify the results that are essential to the purpose of the project. Key results are found by answering the question “How will people’s lives be different because of our effort?” The key results of our project in northern India involve improving participants’ capacity to generate wealth and increasing their household wealth or assets. Key results are not usually measurable as stated, but contain indicators that could be made measurable.

Second, identify one or more indicators of change for each key result. Indicators are particular characteristics or dimensions that show whether individual behaviors or life situations are changing in meaningful ways. They are found by answering the question “How will we know when we have successfully helped the person(s) as intended?” Indicators do not account for all changes, only those essential to the desired results. To choose the right indicator, accurately assess the key result you seek. In the case of reducing economic vulnerability, measuring the change in household income may actually be misleading. Marginal increases in income are spent on many things, not necessarily on improving household living standards; therefore, a focus on the household’s assets or wealth gives a more accurate picture. Families with many diversified assets are less vulnerable to unforeseen circumstances and economic shocks (see Wright). And the choice of which assets to measure—the indicators of reduced vulnerability—is best defined in the local context.

Proxy indicators. Because it’s often difficult to measure outcomes directly, many indicators of change are proxies. For example, it’s difficult to say with certainty that people are growing in their faith, but a promising indicator is their regular participation in Bible studies. By definition, a proxy doesn’t tell the whole story, just as attending Bible studies is not all there is to growing in Christ. A proxy merely allows you to say the behavior or condition is likely to change. That is why a proxy should never be treated as the real thing. A proxy should always be used with caution and reported with caveats. For example, in the past, microfinance institutions commonly used increases in the size of borrowers’ loans as a proxy for business growth and poverty reduction. Closer examination, however, revealed that many people used the additional loan money not for business, but for personal consumption, since consumer credit was not available. Carefully understanding and selecting indicators or behaviors related to a key result will help you avoid misleading reports.

Sample indicators. There are countless numbers of possible outcome measures in humanitarian services (see list below). Various indices identify indicators at the program, community, or national level. The wider the scope, the more complicated measurement becomes. Most ministries can safely measure at the program level and sometimes at the community level. Table 1 contains examples of indicators of change for selected key result categories.

Since measurement is about making comparisons, an indicator needs a baseline—a specific value (behavior or condition) that can serve as a comparison for future studies. The baseline captures the key result indicators before any intervention takes place.

3. Time. The time horizon for measurement—how long to wait before checking results against the indicator’s baseline—depends upon the type of change being measured. Generally, longer time horizons yield better assessments of whether or not sustained improvement has been achieved. For example, a large number of conversions after an evangelistic campaign would seem to belie success; however, without accompanying long-term growth in churches, the ultimate objective has not been met. Assessing the rehabilitation of a trauma victim or measuring the real increase in household wealth takes more time, usually one to two years.

Why Measurement Matters

Now we’re back to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Puck’s mistake was in placing a charm on the wrong pair of eyes. As a result, the lover’s affections fixed on the first person he saw—who happened to be the wrong person. The way we assess ministry outcomes can have the effect of placing our affections on the wrong thing. The solution is to be neither cavalier nor overly cautious in our assessments. The decisive value of ministry is that it changes lives. The best projects show measurable evidence of lives being changed, not just that effort is being made. Measuring outcomes takes us beyond counting numbers, keeping us true to our mission, humble in reflection, and passionate about making a lasting difference in the world.

One final note: However precise our measures, the results are merely a commentary on our efforts, not the measure of success. Success is measured with God’s yardstick. Reflecting upon the results of Nehemiah’s efforts to restore Jerusalem, J. I. Packer puts success in perspective.

After setting biblically appropriate goals, embracing biblically appropriate means of seeking to realize them, assessing as best we can where we have got to go in pursuing them, and making any course corrections that our assessments suggest, the way of health and humility is for us to admit to ourselves that in the final analysis we do not and cannot know the measure of our success as God sees it. (2000, 209)

Measurement matters not as the basis for ethical behavior, but as a point of reference and a commentary on the pilgrimage of faith.

References

Dichter, Thomas. 2003. Despite Good Intentions: Why Development Assistance to the Third World Has Failed. Amherst, Mass.: University of Massachusetts Press.

Easterly, William. 2006. The White Man’s Burden. New York: The Penguin Press.

Kusek, Jody Zall and Ray Rist. “Ten Steps to a Results-Based Monitoring and Evaluation System.” Accessed February 12, 2009 from http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/23/27/35281194.pdf.

Packer, J. I. 2000. A Passion for Faithfulness: Wisdom from the Book of Nehemiah. Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway Books.

USAID EVALWEB. Accessed February 12, 2009 from http://evalweb.usaid.gov.

Wright, Graham A. N. “The Impact of Microfinance Services: Increasing Income or Reducing Poverty.” Accessed February 12, 2009 from http://www.microsave.org/searchresults.asp?NumPerPage=10&id=20&cboKeyword=9& CurPage=6.

________

Links to Measurement Resources

• http://www.liveunited.org/outcomes/index.cfm — Information and links by United Way to resources related to the identification and measurement of program and community-level outcomes

• http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/humanitarian_assistance/ffp/crg/annex-2.htm — USAID defines food security and nutrition related indicators, emphasizes the need for baseline data, and provides a useful resource list

• http://www.who.int/whosis/indicators/compendium/2008/en/ — A database of health indicators and statistics by the World Health Organization

• http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/socind/ — A database of social indicators covering a wide range of subject-matter fields compiled by the United Nations

• http://sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk/SRU47.html — Article in Social Research Update addresses the difficulty of measuring quality of life indicators and includes data resources and indicators used by various national agencies

• http://gsociology.icaap.org/report/cqual.html — A quick primer on “quality of life” and various indices used to describe it

________

Dr. Daniel Rickett is executive vice president of Sisters In Service. He has twenty-five years of field experience working with indigenous missions in organizational and ministry effectiveness. His email address is drickett@sistersinservice.org.

Bob Morrison is director of international programs of Sisters In Service. He is a senior development professional experienced in the funding of grassroots initiatives in over fifty developing countries. His email address is bmorrison@sistersinservice.org.

Copyright © 2009 Evangelism and Missions Information Service (EMIS). All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission from EMIS.