Managing CrossCultural Conflict: A Biblical Example

By Marv Newell

I, along with a hired professional mediator, sat at the large table between the leaders of two respected mission agencies. There was serious conflict between the two ministries. One was using forums and media to publicly condemn the other agency for heresy and ministry misrepresentation. The other, the accused agency, was reeling from lost revenue that was directly tied to the public accusations. The two were at an impasse and I, representing a mission network, had been called in to mediate. If resolution were not achieved there would be dire consequences and major setbacks for both ministries.

It was clear to me from the start that there were crosscultural dynamics involved in the dispute. On one side were two seasoned Caucasian American male leaders, who were long-time believers in Christ. On the other were two influential Middle Eastern brothers, now living the States, who were converts from Islam. Not only was this going to be a theological and missiological hashing out of meticulous issues, it was also to be an exercise in working through different cultural worldviews.

With emotions running high, the discussions started out heated and pointed. Both sides presented justifications for their positions. Neither was prepared to back down. However, after two full days together negotiations brought a breakthrough. It was good to know that disputing American and Middle Eastern believers could work through points of conflict and eventually agree to disagree in a spirit of grace.

Conflict in the Early Church

The crosscultural conflict described in Acts 6 occurred early in the life of the church. That infant church, still centralized in Jerusalem, was comprised of two culturally different strands of Jewish believers. One strand was the Hebrew background believers. These were Jews who were native to Palestine and spoke Aramaic. Since they were “the home team,” their widows were being given preferential treatment in the distribution of food (Acts 6:1). The second strand was the Hellenistic Jews. Ethnically they were Jewish, but they were of the diaspora, having been born in foreign lands and enmeshed in Greco-Roman culture. They grew up in the Greek (Hellenistic) culture and spoke Greek as their primary language. They thought and behaved more like Greeks than Jews.1

The tension that came to a head between them seems at first glance to be a rather petty matter. Daily allocations were made to the poor from a common pool to which wealthier members contributed. Complaints of discrimination came from the poorest of the poor—Hellenistic widows. It seems that the distribution of charity was in the hands of the Hebrew majority.2 Dissonance arose between the two groups.

To their credit, the Apostles were proactive in dealing with this tension within the church. They understood that if the problem was not addressed, a schism based on cultural distinction could erupt. The newborn church could ill afford such a split.

Conflict is a state of disharmony that results from differing beliefs, values, and customs or the act of being discriminated against. Interpersonal conflict, even among believers, is not that unusual. It occurs whenever and wherever human beings live, work, and commune together. Bill Hybels puts it this way:

The popular concept of unity is a fantasyland where disagreements never surface and contrary opinions are never stated with force. We expect disagreement, forceful disagreement … Let’s not pretend we never disagree … Let’s not have people hiding their concerns to protect a false notion of unity. Let’s face the disagreement and deal with it in a godly way … The mark of community—true biblical unity—is not the absence of conflict. It’s the presence of a reconciling spirit.3

If that is true in mono-cultural communities, it is more so in multi-cultural ones. Oneness and harmony are formed on the anvil of repeated interpersonal interaction. Dissonance is created where there is a state of conflict. Hertig commenting on this passage says, “The cost of unresolved conflict can be enormous. When accumulated, conflict brews to a boiling point and results in violent eruptions. Therefore, dealing with conflict openly and in an orderly way is significant, as demonstrated by the apostles and the Hellenists.”4

Paths of Conflict Management

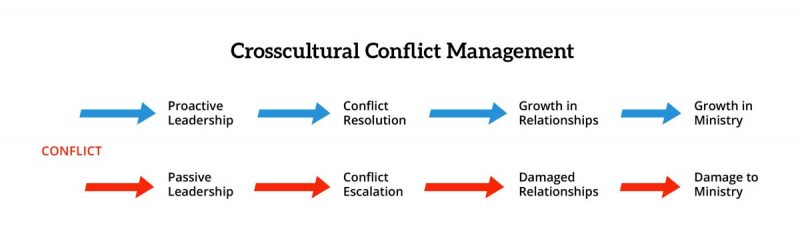

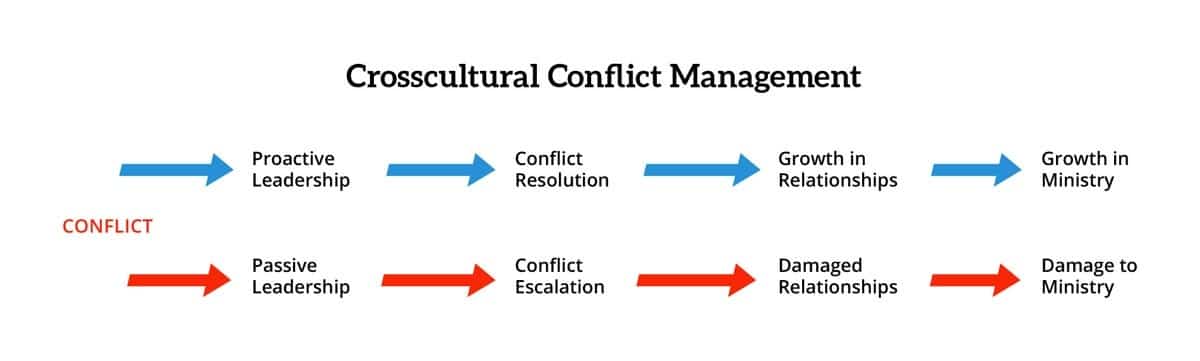

On the one hand, community conflict has the potential to cause serious damage to a community and its influence. On the other hand, it has the potential to move the community and its influence into growth and positive influence. The following, slightly modified from Evelyn and Richard Hibbert,5 illustrates the two alternative outcomes of interpersonal conflict.

Crosscultural Conflict Management

The apostles dealt with this conflict in an admirable manner; the entire corrective process is coated with spirituality. Their devotion to prayer and the Word (Acts 6:4) empowered them to act wisely and provides us with basic principles for crosscultural conflict management.

Equality: Though people are different, none are superior and none are inferior—all are of equal value and should be treated equally. In the body of Christ there is no distinction of class and importance. There should not be ethnic discrimination, “neither Jew nor Greek;” class discrimination, “slave nor free;” or gender discrimination, “male and female” (Galations 3:28). The church learned this principle early on by way of this internal conflict.

Sensitivity: Be sensitive to the needs of others, especially those who are disadvantaged. It appears that the Hebrew faction was clueless of the hurt they were causing the Hellenistic widows. They seemed to be insensitive to the offense until it was brought it to their attention.

Discovery: In times of crosscultural tension, become knowledgeable. The twelve apostles brought everyone together to discover the core problem (Acts 6:2). No doubt there was a lengthy discussion about the issue. They took the time to search out the particulars, separating fact from fiction. Many times at this stage of information gathering, a lot of emotion is vented. Good leaders wade through and wait through the time of emotional expression without getting caught up in the moment themselves. This written account is devoid of emotional excitement, though there surely must have been plenty.

Ability: Be helpful according to one’s ability and understanding. The apostles understood both their authority and limitations, and balanced them with their primary focus—spiritual ministry. They didn’t micro-manage the situation, but rather handed it over to others who could manage it for them.

Mediate: As a mediator, don’t take a side and don’t take offense. Graciously mediate from a position of authority, and once the problem is pinpointed, don’t feel insulted. Some leaders think that interpersonal tension in an organization is a reflection of their weak leadership skills. After all, they reason, if they were competent leaders, problems like this would not arise. Yet, that is just not true. As the earlier quote from Hybels makes clear, wherever you have people gathered, there you will have conflict. The apostles were not offended that this problem emerged under their leadership. Rather, they took control of the situation and led the group through a corrective process.

Participation: Attempt to solve the conflict in conjunction with those involved. The apostles didn’t make a unilateral decision. Rather, they backed off and delegated the matter to others more knowledgeable and closer to the situation (Acts 6:3).

Agreement: Make sure both sides agree to the terms of the solution and the means of rectification. Notice that their plan of action “pleased the whole gathering” (Acts 6:5). They achieved buy-in from everyone. Thus, it was easy to also get both sides to agree on the solution. In this instance, judging by their names, the ones chosen to manage the process from then onward were all Hellenistic Jewish believers. This solution seemed to please everyone, especially the apostles who, “prayed and laid their hands on them” (Acts 6:6) as official confirmation of agreement.

Benefits of Conflict Resolution

When interpersonal conflict gets resolved, good things happen. Disharmony turns into accord, and discontent into satisfaction. People get along with each other and together shoulder responsibilities that make the community stronger. In this case, “the word of God continued to increase, and the number of the disciples multiplied greatly in Jerusalem, and a great many of the priests became obedient to the faith.” (Acts 6:7). Increased influence and multiplication of numbers were the outcome of the resolved conflict. Rather than a schism fragmenting the church, solidarity propelled it forward.

Takeaways for Today

Interpersonal conflict is unavoidable. Whether from differences of opinion based on beliefs, values, and customs, or as a result of unwarranted discrimination, dissonance happens. This is all the more true when people of different ethnic backgrounds attempt to work together. However, there are biblically based principles for resolution. The apostles modeled these principles through the leadership they exercised, managing a seething undercurrent in a church divided along cultural lines.

Working through conflict is stressful, but the joy of bringing people, especially of two cultural backgrounds, to understanding and agreement makes the effort rewarding. In most instances, ministry is enhanced and growth results. Conflict resolution results in restoration of relationships, which in turn produces multiplication.

Marv Newell is Senior Vice President of Missio Nexus. This article is adopted from his just released book, Crossing Cultures in Scriptures: Biblical Principles for Mission Practice (IVP, 2016).

References:

- John R.W. Stott, The Message of Acts, 120.

- F.F. Bruce, Commentary on the Book of Acts, 128.

- Evelyn & Richard Hibbert, Leading Multicultural Teams, 138.

- Young Lee Hertig, “Cross-cultural Mediation: From Exclusion to Inclusion,” in Mission in Acts: Ancient Narratives in Contemporary Context, 64.

- Hibbert, ibid, 142.