Related Articles

Welcoming the Stranger

Presenter: Matthew Soerens, US Director of Church Mobilization, World Relief Description: Refugee and immigration issues have dominated headlines globally recently. While many American Christians view these…

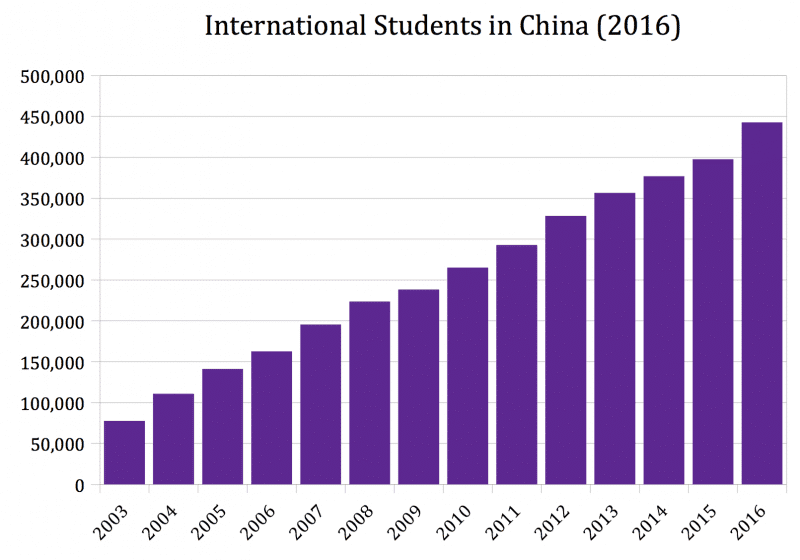

International Students in China: Who Will Reach This Vast and Strategic Yet Invisible Group?

Wearing her hijab, “Mounia” from Yemen heard the gospel and felt the love of God in our international church because of her Rwandan classmate’s invitation and her husband’s permission. Without Arabic or visa for Yemen, instead of flying to Sana’a, we walked two meters to welcome her. From a country with 0.03% evangelicals, could she take the gospel back home?

Identity, Security, and Community

By Dick Brogden Jeddah, KSA. November 2019 Synopsis: God is light and in Him there is no darkness at all (1 John 1:5). It is…

From Unhealthy Dependency To Local Sustainability

Presented by: Jean A. Johnson, Executive Director of Five Stones Global Description: It takes a great amount of intentionality to create a culture of dignity,…

Problems Hindering North American Church Planting Movements

This article offers some necessary theological and missiological shifts to help facilitate church planting movements.