Related Articles

Do Universals in Music Exist?

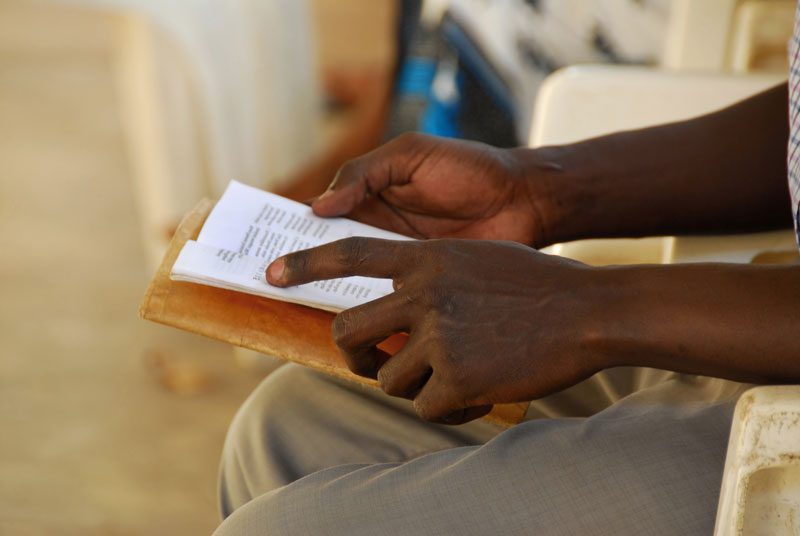

The missions community is becoming increasingly aware of music as a means to understand peoples and communicate the gospel to them in culturally relevant forms. Undergirding this growing emphasis is the conviction that music must be understood and communicated in its local variations.

Welcoming the Stranger

Presenter: Matthew Soerens, US Director of Church Mobilization, World Relief Description: Refugee and immigration issues have dominated headlines globally recently. While many American Christians view these…

Many Ethnicities, One Race

The idea of “races” is fiction. There is but one human race descended from one parentage, all of whom are created in the image of God spiritually, rationally, morally, and bodily. Our failures at unity is a failure to ground our ideas of ethnicity and “race” in the person and work of Christ Jesus.

From Unhealthy Dependency To Local Sustainability

Presented by: Jean A. Johnson, Executive Director of Five Stones Global Description: It takes a great amount of intentionality to create a culture of dignity,…

La Vida Profunda: Contextualizing Spiritual Formation

Case study of how one missionary team (Mission Mexico City) tried to contextualize the spiritual formation process with urban youth in Mexico City.