Related Articles

What about People-Movement Conversion?

Although the “church growth” school of thought has made substantial inroads into missionary thinking, there is a continuing reluctance on the part of many evangelicals to accept “church growth” concepts.

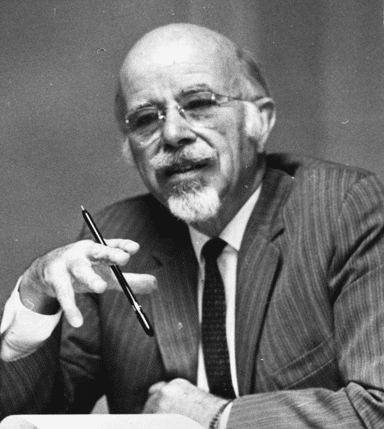

Celebrating Donald A. McGavran: A Life and Legacy

McGavran was a prolific writer of letters, articles, and books, as well as a world traveler. No one, to my knowledge, has visited as many mission fields, conducted as many interviews, or researched the growth and decline of Christian churches as widely as McGavran. He influenced mission theory and practice internationally and the movement he started continues to move forward, empowered by appreciative followers.

Missiological Pitfalls in Mcgavran’s Theology

I have learned much from the writings of Donald McGavran and from those of his colleagues in the church growth school of missiology. Surely few evangelicals will quarrel with the gospel’s insistence that the obedient church can expect to grow.

Missiological Pitfalls in Mcgavran’s Theology

I have learned much from the writings of Donald McGavran and from those of his colleagues in the church growth school of missiology. Surely few evangelicals will quarrel with the gospel’s insistence that the obedient church can expect to grow.

Donald Mcgavran’s Legacy to Evangelical Missions

Perhaps no other person has had a greater influence on missions in this century.