Related Articles

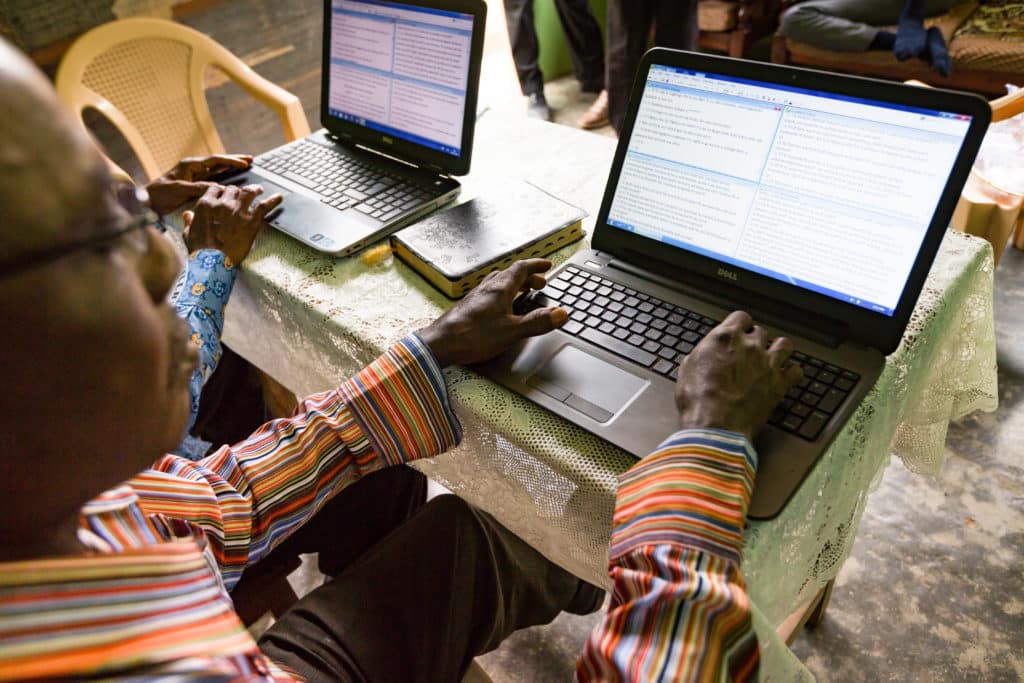

The Landscape of Bible Translation in the 21st Century

By Phil King and Dick Kroneman | The rich and diverse landscape of Bible translation, today, brings together past wisdom and present innovative opportunities to meet ongoing challenges and explore new territories.

Holding the Rope: Making Space for Prayer in the Bible Translation Movement

By Jo Johnson, Sineina Gela, Ann Kuy, Nancy Duncan, and Zac Manyim with Gwendolyn Davies and Jim Killam | Holding the rope is a visual symbol of unity and togetherness in prayer. As prayer leaders in the Bible translation movement, we have learned that when we stay within the confines of our own cultures in prayer, we are the poorer for it. Each culture provides unique reflections of God through distinctive approaches to prayer. And when we don’t embrace this, there are things that we don’t learn.

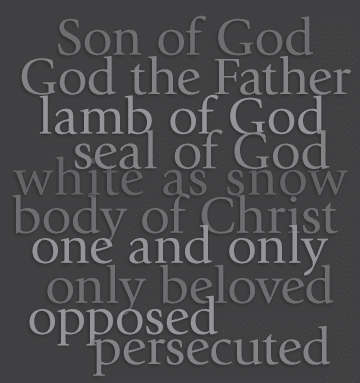

Four Qualities of a Good Translation and the Divine Familial Terms Controversy

MY PURPOSE IN WRITING THIS ARTICLE is to assist both translators and non-translators in understanding the proper and traditional application of meaning-based translation principles to the translation of ‘Son of God’ and ‘God the Father.’