Related Articles

Context is Critical in Islampur Case

This article is a response to “Danger! New Directions in Contextualization,” by Phil Parshall in the October 1998 issue of EMQ.

Welcoming the Stranger

Presenter: Matthew Soerens, US Director of Church Mobilization, World Relief Description: Refugee and immigration issues have dominated headlines globally recently. While many American Christians view these…

ONLY vs. Primary and Secondary: The Key to the Missionary Motivation Problem

In 1900, Andrew Murray tackled the key question to the missionary problem as to why there were so few missionaries. In his report to the ecumenical missionary conference held in New York in April, he thought the answer was simple; it was the Lordship of Jesus Christ. Though I totally agree, I think there is much more to it than simply a Lordship question. I believe it is in how we, the church, view the cross.

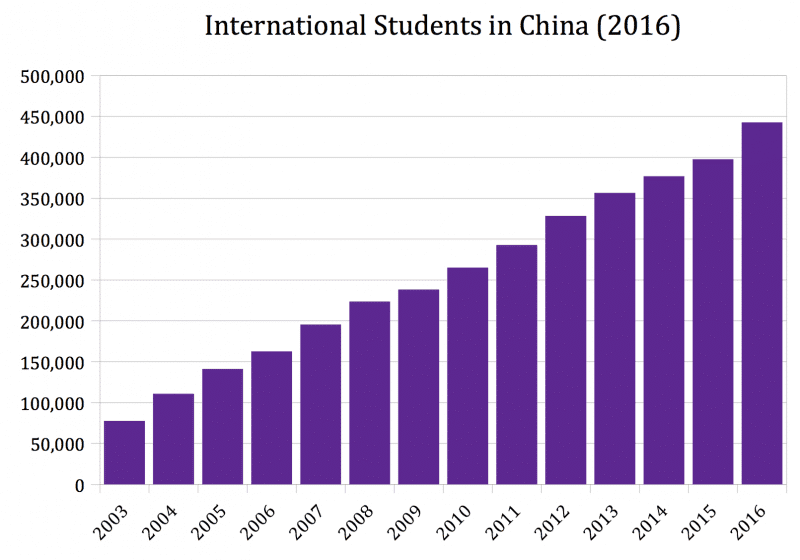

International Students in China: Who Will Reach This Vast and Strategic Yet Invisible Group?

Wearing her hijab, “Mounia” from Yemen heard the gospel and felt the love of God in our international church because of her Rwandan classmate’s invitation and her husband’s permission. Without Arabic or visa for Yemen, instead of flying to Sana’a, we walked two meters to welcome her. From a country with 0.03% evangelicals, could she take the gospel back home?

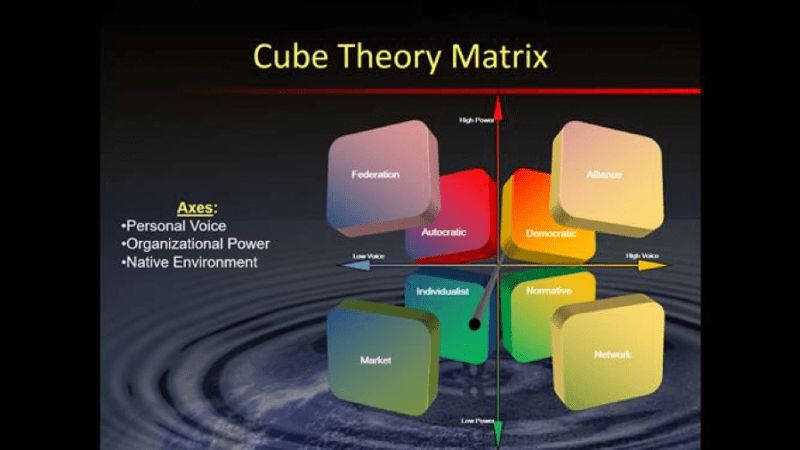

Leading Mission Movements

We live in an unprecedented period of mission history. The new paradigm of “from anywhere to everywhere” is by nature complex, resulting in an increasing need to partner with others for effective ministry. The challenge of connecting with potential partners in the global context is best done in and through the evolving world of networks.