Successful Partnership: A Case Study

by Rick Kronk

A tremendously effective partnership between a group of missionaries to North Africans in France and a local French church led to the formation of a ministry model for the future placement of teams in France.

No matter what happens, Rick, we want you to do what you came here to do.” Such was the counsel of the elders of the local French church with which we had come to work. We, a team of two couples and a single, had moved to Grenoble, a medium-sized French city of approximately 400,000, in late 1999, after completing an in-house demographic study which included a search for a local church which shared our burden: to reach the North African immigrant community—men and women from Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. Our demographic study involved compiling census data from the 1990 census in an effort to determine the French cities with the ten largest populations of North Africans. Although several years had passed by the time of our study, we made the assumption that immigration patterns had not changed significantly enough to throw off our conclusions: in effect, the top ten cities in 1990 would still be the top ten cities ten years later. Grenoble weighed in at number seven in terms of North Africans. There were nearly fifty thousand, with an additional several thousand students of North African origin at the local university.

Identifying a local French church which shared our burden was not as simple. Church history, coupled with popular political opinion, predisposed many to uncertainty with regard to establishing a focused North African ministry as part of, or alongside of, current church activities. Not that any were out-and-out opposed, but the question of what happens when several of these Arabs become Christians and begin to bring their friends and “date” young people from the church made some uncomfortable.

Prayer and conversation with prominent church leaders in various cities in France eventually led us to a local Brethren church in Grenoble. Initial contact with their lead elder, JLT, resulted in an invitation to discuss our vision and consider a possible partnership. In our presentation, we explained that we had an interest in partnering with a local French church to see a local North African church implanted which would be a sister church and eventually led by North African leadership. We explained that we were preparing to work with a team of five (the two couples and one single noted above) initially, that we were more than happy to include church members who would like to participate in the ministry, and that we were willing to coordinate our ministry such that it complemented and did not compete with the ministry of the local church. Apparently, our vision was sufficiently palatable that JLT felt inclined to offer us an invitation to discuss our vision with the elders. A short time later we met with the church elders to present our vision and to propose a partnership. Seeing that the vision was compatible with where this church wanted to go, the elders invited us to begin our work.

As a first step, and indication of their commitment to the cooperative effort, they proposed a meeting at which they would invite specific individuals from the church whom they knew would be predisposed to support our work. This included a mixed North African-French couple and a North African believer, both of whom had been in the church for several years. From the point of view of the church, JLT said,

We were happy to have someone on the “inside” to work with us to try to reach these people who were all around us. We also knew that we had a need for both the resources and the know-how that this team brought. Because we had good experiences with missionary partners in the past, we were more than willing to enter into a partnership with them.

Expectations and Concerns

Inevitably partnerships, like marriages, bring both blessings and challenges, joys and disappointments, as both sides discover who the other person(s) really is (are). Our experience in Grenoble was no different. Our first expectation as an American team was for the establishment of a formal relationship that we could “contractualize,” complete with a mission statement, strategy proposal, list of written expectations, and other terms giving both parties a clear delineation of who was responsible for what, where the boundaries of authority lay, as well as a signatory block committing representatives from both sides to the partnership. To our surprise (a rather pleasant one, as it turned out), our French partner didn’t think such a contract was necessary. Instead, they insisted on a “contract” of communication and visibility, which they boiled down to two things: (1) be involved in the life of the church beyond our own ministry niche and (2) be represented at elder and other church meetings as requested.

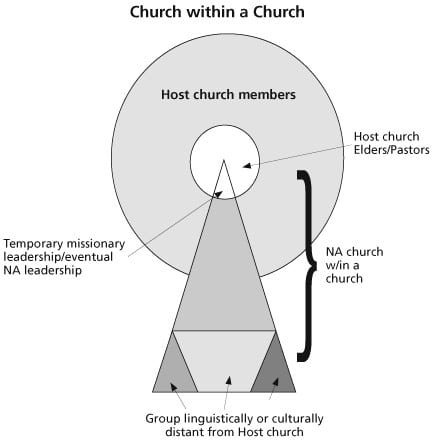

Their history with missionaries in the past had helped them see that if these two conditions were faithfully met, then a formal contract was not necessary. Eventually, however, we found it helpful to create a visual image of how we related to the church in terms of ministry and lines of authority. The diagram below, which we referred to as “a church within a church,” was our best attempt to picture this relationship. The large circle represents the host church membership. The central, smaller circle represents the church leadership, in this case, elders and pastors. The large triangle represents the North African group which has a number of particularities.

The North African leadership is represented by someone (or several persons) as part of the host church leadership. Initially, this role was filled by one or two missionaries who would eventually be replaced by qualified North Africans.

That part of the large triangle which extends beyond the large circle represents those of the North African group who are associated with the host church, but may or may not attend regularly.

The smaller triangles within the large triangle represent those North Africans who are associated with the North African group, but who have little or no contact with the host church because of major language or cultural barriers.

As time went on, a second challenge reared its head and threatened to distract certain members of our team. This challenge is called the “we need you” challenge. In short, the French local church is in need of competent contributors at all levels. Increased lay-training is helping the local church respond to ministry needs, from worship to Christian education (i.e., Sunday school), but the presence of a team of equipped and trained church workers is hard to overlook. So whereas we were willing and ready to contribute to the life and ministry of the church, we were encouraged by the local church elders not to get so involved that we gave up the work for which we had originally come to France.

In practical terms, those on our team who were competent in preaching would preach from time to time. Those who had music skills assisted in worship leading. Others helped in the children’s Sunday school or took turns on the church cleaning rotation. Everyone on our team participated in city-wide outreach events or special events in the life of the church, and we were always ready to provide training tools (e.g., understanding Islam, how to reach Muslims) to local churches—whether in a church-wide event, small group, or one on one.

A third challenge we faced was cultural. The North African Muslim in France faces a host of challenges due to the fact that his or her culture, religion, and family life is so different, and in many ways, opposed to that of French culture, religion, and family life. Despite wishful thinking, these differences do not automatically disappear for the North African once he or she becomes a Christian. Although he or she may be a new creature and not unequal to others in God’s eyes (Gal. 3:28), the fact of the matter is that he or she will still struggle to eat the ham offered at the church potluck dinner and drink the wine served at communion. He or she will still prefer to come uninvited to your home and expect to stay as long as needed. Schedules, clocks, appointments, etc., are secondary; relationships are primary.

Thankfully for our partnership, the leadership and membership of the church caught on to this quickly and from the start made a point to minimize the non-essentials and cultural obstacles that could have inhibited our North African friends. For example, they always made sure grape juice was available for communion and that many non-pork items were served at church potlucks.

Benefits Received

JLT put it like this when asked what the church received from this partnership:

The missionary team brought energy to the overall life of the church. Their focus on a particular ministry and the results that we saw as North Africans came to faith and began to participate in the church helped us see that it was possible to reach this community. This is something for which some of us had been praying for many years.

One joint decision we made early on was to arrange for worship services to be led by the missionary team focusing on North African ministry. These services would include music led by the mission team (often bilingually in French and Arabic), a sermon by a trained North African pastor, and testimonies. Such a service was always followed by a large meal to which everyone was invited. The result of these services helped the church not only to see people from a part of the world of which they were not fully aware, but also to be spiritual recipients—overturning some of the prejudices and healing from the scars of the colonial era.

As the missionary team, we gained invaluable experience in partnering. One of the most important aspects was the role history played in ministry. By history, I mean the collective efforts and results of the missionaries who had come before us in the same location. We, as a team, were not conscious of the historical and religious-political context into which we were arriving with our grand ideas and idealistic ministry plans. We had little knowledge of what had happened missiologically prior to our arrival, and we were ill-equipped to respond to the complex web of inter-church and church-government relationships. Fortunately, the local church leaders took us by the hand and helped us meet the right people, represented us before local officials, and defended our rights as foreign workers in their country. They also took the time to tell their story and that of the missionaries who had come before us, careful to instruct us as to the “dos and don’ts” so that we would have the best experience possible.

The Result: A Ministry Model for the Placement of Teams in France

Our experience in Grenoble has resulted in formulating a ministry model for the future placement of teams in France. Confronted as we had been by the cumulative (and not always positive) experience between churches and missionaries—together with the sometimes complicated prevailing political and popular opinions of North Africans (and later, during the Iraq War, attitudes toward Americans in particular)—we soon recognized the necessity of finding a “friendly” partner with whom we could work: a partner who would bring legitimacy to our efforts and be able to carry on the effort after our departure. If we were to summarize our ministry model for partnership in France, it would look like this:

Step one: Identify a local church that is willing to allow missionary-directed ministry which is integrated into the local church ministry or cooperates by not competing with local church ministry. The key to this is prayer: prayer to identify possible local churches that might be willing to explore a partnership; prayer with and for the potential local church partner to see if the partnership should be entered into; and prayer all along the way so as to keep God’s purposes the primary ones.

In addition to the active necessity of prayer, finding such a partner should involve understanding the ministry history of the local church as well as prevailing attitudes and experiences with the proposed ministry venture. What we learned in France was that we, as the incoming mission, were not working from a clean slate. Rather, we were only the next ones in line of a considerable history of mission efforts before us. We were in part evaluated initially through the lenses of what had transpired in the past. Our “glorious” vision was for many a very foreign idea that would require time and evidence that what we envisioned would be valid for the local church as well. Because of this mix of history, culture, missiology, and church polity, not only was patience a fundamental ingredient, but even patience had to take a backseat to humility and respect for the host local church. With regards to our partnership with a French church, whatever criticism we may have had of them, France was and still is their country. As international foreign workers, we had to realize and accept the fact that we were on their turf, and whatever we did—in the name of the gospel—they would have to live with it…even after we were gone.

Step two: Establish a working agreement, whether formal or informal, which both parties understand and which outline at least levels of cooperation, communication, authority, and terms of continuation. Such agreements will inevitably vary from situation to situation but should be maintained in all good faith. Despite our desire to establish a partnership complete with written objectives and clauses and detailed lines of authority in keeping with what we saw as “normal,” the local church was much happier to work instead off of a relational basis. This relational agreement involved significant potential risk on their part, but their experience as a missionary-friendly church gave them confidence that it could work. All they asked was that we would be involved in the life and ministry of the church outside of our ministry niche, and that we would be represented as requested at regular elder meetings—two conditions we were more than eager to meet.

Step three: Propose a transition or trial period during which initial ministry is carried out and integration of local church members is attempted. Such a transition period allows for learning the local context, building trust between the local church and the missionaries, and identifying hidden “surprises” that may turn out to be accelerators or obstacles to the ministry and call for a “re-think” of the ministry plan. A trial period also allows both sides to determine if this is a good ministry fit and if the partnership should go ahead. In Grenoble, as part of our coming to terms with a partnership, we built in a trial or transition period to our early phases. For nearly one year prior to actually moving team members into Grenoble, we made trips to Grenoble for the purpose of ministry with the church approximately once a month. Over the course of that year we built credibility, developed relationships with church leadership and church members, and began to forge a clearer picture of how to proceed.

Step four: Make time to evaluate relationships, plans, strategies, and results—both positive and negative. Such efforts to be vulnerable provide opportunities for mutual prayer and encouragement, and for the humble of heart, the possibility of learning something important from the local church partner. Another thing we learned was that evaluation does not always have to be formal and serious. We enjoyed a number of great celebratory moments with our French brothers and sisters around the table, following a baptism or other special event.

Conclusion

“Rick, what you (and your team) have been able to do here has been nothing short of amazing. We could have never imagined that we would be so encouraged as a church by the contributions of the North African brothers and sisters that you have helped us get to know and love.” Our time in Grenoble was a successful experience due in large part to the partnership with the local French church. They valued our presence and demonstrated it by praying for us and inviting us to plan church-wide events that would highlight our North African ministry.

They gave us access to their facilities, people, and resources. They joined with us in celebrating when things went well and grieving when things went poorly. But mostly, they got personally involved with us. Many gave hours and hours to helping those struggling with immigrant/refugee issues. Many gave financially to our North African friends in need. Several participated with us in evangelistic outreach and discipleship. And they never stopped encouraging us to continue to do what we had come there to do.

….

Rick Kronk and his family spent twelve years church planting among North African immigrants in France. Rick is currently involved in curriculum development and teaching in the areas of Islam and church planting.

EMQ, Vol. 46, No. 2, pp. 180-186. Copyright © 2010 Evangelism and Missions Information Service (EMIS). All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission from EMIS.