Related Articles

Running the Race on African Turf

I didn’t know who was going to win the 2004 Athens Olympics marathon. I did know, however, who wouldn’t win.

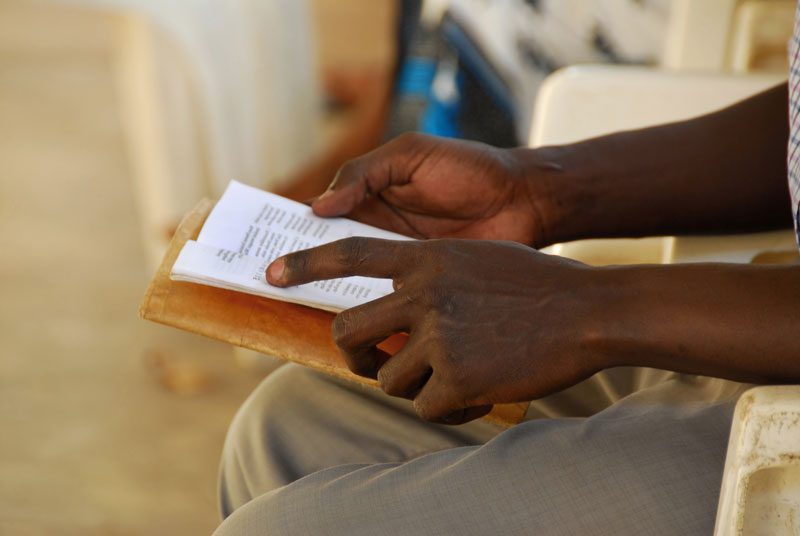

Time for African American Missionaries

While teaching a group of Ugandan church leaders, I mentioned how few African Americans were engaged in global missions. Okiru Ezekiel jumped up and shouted, “Tell them to come!”

Time for African American Missionaries

While teaching a group of Ugandan church leaders, I mentioned how few African Americans were engaged in global missions. Okiru Ezekiel jumped up and shouted, “Tell them to come!”

Many Ethnicities, One Race

The idea of “races” is fiction. There is but one human race descended from one parentage, all of whom are created in the image of God spiritually, rationally, morally, and bodily. Our failures at unity is a failure to ground our ideas of ethnicity and “race” in the person and work of Christ Jesus.

Sing Africa!

A pastor from the US, just last year, was invited to speak at a weeklong Christian conference in Malawi. The music that preceded his message horrified him.