Personal Contact: The sine qua non of Twenty-first Century Christian Mission

by Todd M. Johnson and Charles L. Tieszen

Statistics from the World Christian Encyclopedia appear to indicate that less than sixteen percent of non-Christians know a Christian; however, the Bible indicates that personal contact is crucial in evangelism.

In recent years, the concept of translation has become one of the significant motifs in Christian mission, not only for Bible translation but for the serial expansion of Christianity around the world (Sanneh 1989; Walls 2002). The starting point of translation is personal contact in which a Christian from another culture or tradition learns the language and culture of the people he or she is trying to reach. In normal missionary practice, this means making friends. With this in mind, we have recently been asked, “How many Muslims have a Christian friend? How many Hindus personally know a Christian? How many Buddhists have significant contact with Christians?” Considering these questions carefully, we realized that the concept of personal contact was built into the measurements we had previously made related to evangelization of ethnolinguistic peoples.

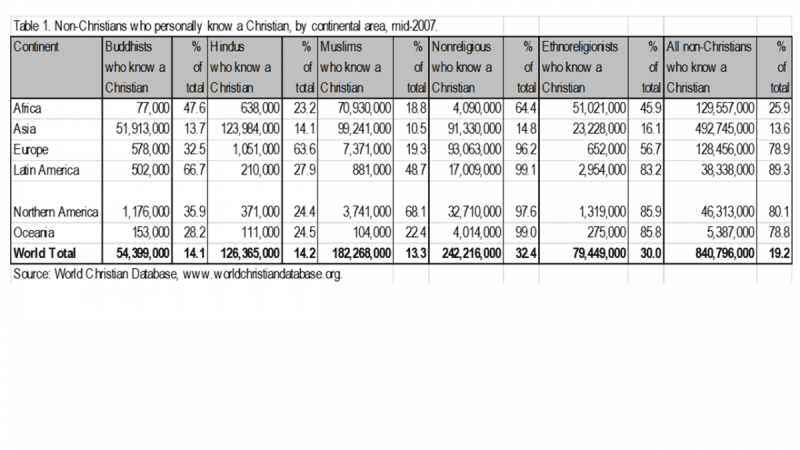

For our study of evangelization, we isolated twenty variables measuring evangelization among every ethnolinguistic people in the world (Barrett and Johnson 2001, 756-757). Two of these variables relate very closely with personal contact between Christians (of all kinds) and non-Christians. (Evangelicals are a subset of all Christians and would thus have a lower rate of contact with non-Christians; additionally, one would not want to disparage positive contact between non-evangelical Christians and non-Christians). The first, “discipling/personal work,” is an indication of how much contact local church members have with non-Christians. The second, “outside Christians,” extends this concept further by looking at the presence of Christians from other peoples who live nearby. Under normal circumstances, the more Christians there are nearby, the more likely the contact between Christians and non-Christians. Thus, for every non-Christian population in the world, there is an indication of Christian presence and contact. A formula was then developed to make an estimate of those personally evangelized (contacted) by Christians. The formula applied to each ethnolinguistic people is shown below. Separate values for these two codes are reported for each ethnolinguistic people. These are added up for each country, region and continent, producing a global total (Barrett, Kurian and Johnson 2001, 30-241). The results of this method are summarized by continental area in Table 1 on page 496-497. While these numbers are estimates, we think they offer a preliminary assessment of a critical shortfall in Christian mission.

A careful examination of Table 1, “Non-Christians who personally know a Christian, by continental area, mid-2007,” reveals several significant findings.

1. Buddhists, Hindus and Muslims have relatively little contact with Christians. In each case, over eighty-six percent of all these religionists do not personally know a Christian.

2. The nonreligious are closer in touch with Christians than other religionists except in Asia. This finding is not unexpected since some nonreligious or atheists in the West are former Christians reacting against Christianity.

3. Tribal religionists have more contact with Christians. This is likely due to the fact that tribal peoples were the focus of Christian mission in the twentieth century.

4. Non-Christians in Asia are more isolated from Christians than in any other continent in the world. This is likely due to two factors: isolation of Christians under Buddhist, Hindu and Muslim rule; and relatively few missionaries sent to Asia from the rest of the world.

5. Muslims in Africa are only slightly more in contact with Christians than the world average for Muslims. Christians in the global South face a formidable challenge in their lack of contact with non-Christians, especially Muslims.

6. There is a sizeable difference between Muslims who know Christians in Europe and those who know Christians in North America. This may reflect the tendency of European Muslims to isolate themselves (or be isolated by others) in Muslim communities.

7. Christians are more in contact with non-Christians in heavily-Christian contexts. The migration of non-Christians from Asia and Africa to Europe and North America represents a great opportunity for Christians to offer hospitality and friendship.

8. Globally, over eighty percent of all non-Christians do not personally know a Christian. This lack of contact is a fundamental shortfall in Christian mission and evangelism.

Such statistics compel us to re-examine a biblical theology where personal contact and evangelism are connected. Even within the Old Testament, Yahweh models a characteristic which places him in close, personal contact with his people. As the Israelites journeyed to the Promised Land, Yahweh told Moses, “Then have them [the Israelites] make a sanctuary for me, and I will dwell (šakan) among them” (Exo. 25:8). This sort of “dwelling” (šakan) is different from other types of personal contact in the Bible. In fact, the Hebrew verb used here, šakan, “…underscores the idea not of loftiness but of nearness and closeness” (Harris 1980, 925). Yahweh is not merely paying a temporary visit to the Israelites. Much more, he distinguishes himself from other Ancient Near Eastern gods by coming down to his people. He was not content to menacingly hover over them from the heavens. Yahweh’s desire was to intimately dwell with his people. In the New Testament, this characteristic is extended and fulfilled in Jesus Christ. As the incarnate Son of God, Jesus not only came down to be with humanity, he became one of us as well. In John 1:14 we read that Christ “became flesh and made his dwelling (skenoo) among us” (note the etymological similarity between škn in its original vowelless form and skenoo which may point toward an attempt to preserve the theological significance of Yahweh’s presence carried forward through Christ, his son; Carson 1991, 127-128; Beasley-Murray 1987, 14). Like Yahweh, Christ came to be with his people in a unique way that was personal, permanent and divine. In this way, personal contact is a central feature of the person and work of God.

Christian conversion in the early Church carries this characteristic forward as a model for evangelism. For instance, although Christ alone supernaturally initiates Paul’s conversion, it is Ananias who follows this experience by personally laying his hands on Paul, resulting in the restoration of his sight and his being filled with the Holy Spirit (Acts 9:10-19). Similarly, Philip personally interacts with the Ethiopian eunuch (Acts 8:26-39); there is personal contact and evangelism between Peter and Cornelius (Acts 10:19-48); and Lydia responds to Paul’s personal message in Philippi (Acts 16:13-15). From these experiences, it is clear that it is God’s desire that we partner with him in evangelism by fostering personal contact with people. This model of “incarnational evangelism,” set forth by Christ and demonstrated in the experience of the early Church, prioritizes personal contact between Christians and non-Christians. Personal contact is an intrinsic characteristic of God, forms the core of the gospel message and frames a biblical theology of evangelism. In this light, it is Christ’s desire for us to model the same approach—to personally incarnate his message among those he calls to himself. We do this by being with those people and becoming like them (1 Cor. 9:22).

The rise of media and technology in the twentieth century forces us to face new issues in evangelism and incarnation. As William Nottingham notes, “Evangelism changes and must not be thought of as static and defined dogmatically. It is ever-evolving with the circumstances of history” (1998, 313). In keeping with the need for adaptation, Clarence Jones’ HCJB radio has now been broadcasting the gospel for seventy-five years. Their messages have reached all over South America and into continents even further away. Similarly, the Jesus film and other similar presentations can be viewed or listened to via television or the Internet. Such technological developments have made a host of positive contributions. Through these types of technology, audiences across wider geographical areas can be reached with less manpower. Further, because of new developments in media and technology, the gospel can be preached in areas where Christian missionaries are not able or allowed to be physically present. These positive contributions notwithstanding, unfortunate shortcomings are seen where there are gaps between gospel presentations and personal contact. Nottingham warns,

Increasing technology and the new forms of communication . . . [mean] that life in affluent societies will be spent more and more in physical isolation because of the independence of this source of knowledge. This will result in the rarity and need for face-to-face contact with people, not just “chat rooms”… [so that] the gospel incarnated in a loving and serving community will have new relevance for a truly human consciousness. (1998, 314)

In essence, the globalization brought on in part by technology has at once drawn the world closer together and placed individuals in isolation from each other. Without personal contact, our ability to soundly disciple new believers and maintain a healthy community of faith may be compromised. Clearly, our use of media developments and cutting-edge technology must be joined with a biblical theology of evangelism that stresses personal contact.

In the end, of course, it is God who is the ultimate evangelist, the one who alone initiates and omnipotently calls those to himself (Wells 1987; Packer 1991). His ability to do so independently of humans is illustrated, for example, by many Muslims who choose to follow Jesus Christ because they dreamt of him (Musk 1988, 163-172; Woodberry and Shubin 2001, 28-33; Love 2000, 156-158; Sheikh and Schneider 1978) or by Hindus who become Christians after a prayer said to Jesus results in healing. Such supernatural contact, however, does not mitigate the importance of personal contact. Consider, for example, a Muslim who dreams of Jesus Christ, but is re-directed to Islam after consulting a local imam for an interpretation (Musk 2004, 167-168; Love 2000, 162). Similarly, many Hindus have witnessed Christ’s miraculous healing only to count him as one more of their 333 million other gods. Examples such as these show us that it is often God’s desire to use believers as his personal instruments to incarnate his message among those who seek to follow him. In fact, a recent survey of Muslim background believers reveals that “by far, the reason found most compelling for the greatest number of Muslims who have turned to Christ is the power of love” (Woodberry and Shubin 2001, 32). This love is further simplified into two categories: love demonstrated directly by God (supernatural contact) and “love by example” or personal contact (Woodberry and Shubin 2001, 32). Personal contact is not only important, but foundational to a biblical theology of evangelism.

If our estimate that eighty-six percent of Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists (or eighty percent of all non-Christians) do not personally know a Christian is correct, this raises four important questions.

1. Does this reflect the human tendency to isolate one’s self among his or her own social, ethnic and/or cultural group? In the West, increasing diversity brings increasing cultural isolation. A typical Western metropolis has its Chinatown, Little Saigon, Muslim quarter, etc. Except for a non-personal, cross-town commute, people can live the majority of their lives without really venturing outside of the comfort of similarity. The same can be said in the non-Western world where people can be isolated by tribe, cultural group, religion and/or language.

2. Are Christians simply unaware of the major world religions? This lack of awareness includes not only religious knowledge, but an unwillingness to learn the languages and cultures of Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists as well. In the West, if Christians have little knowledge of non-Christians in their own communities, what can we say of their knowledge of Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists in their traditional homelands? Of course, this Western unawareness has its non-Western counterpart. This is true, for instance, in Nigeria, India or Indonesia, where peoples are split linguistically, religiously and geographically. If non-Christian peoples are to hear of Christ, Christians must be willing to cross cultures, learn languages and become religiously aware.

3. Does the unawareness described above extend to an unawareness of the world’s most unreached people groups? The majority of unreached peoples are Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists located in areas where access to the gospel, not to mention personal Christian contact, is limited, if not totally inaccessible. Even if we are aware of unreached people groups, the fact that nearly ninety percent of Christian resources for mission are directed at Christians tells us that we need to re-focus mission and evangelism on carefully defined unreached people groups (Barrett and Johnson 2001, 40). Such a re-focus may allow for increased personal contact between Christians and Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists.

4. Among hard-to-reach people groups, do our ministries rely too heavily on non-personal methods of evangelism? The importance of incarnation in a biblical theology of evangelism suggests that the positive contributions of media and technology in evangelism cannot be utilized at the expense of personal contact. Among Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists, we must emphasize placing personal contact alongside our appropriate use of non-personal methods of evangelism.

MOVING FORWARD

With these reflections in mind, we offer four suggestions that may help to bridge the current gap between Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists and personal contact with Christians.

1. Stress the importance of engaging the Majority World religions by learning what adherents of such religions believe, why they believe it and where they live (lists of resources can be found at www.beliefnet.com and www.mislinks.org). It is perhaps not only our unwillingness to interact with Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists that accounts for a severe lack of personal contact, but an ignorance of these religions and their followers. Of course, this does not imply that all Christians must be experts on religion. What we are advocating is that Christians become religiously informed in ways that foster healthy, inspired and personal contact. Additionally, engaging religions is important for those who live in areas dominated by Islam, Hinduism or Buddhism. For instance, some Pakistani Christians, given an abhorrence of Islam, have refused to reach out to Muslims. The same can be said for some Arab Protestants or even of some Western missionaries in the Middle East, historically and presently, who insist on ministering only to Arab Orthodox Christians.

2. Stress the importance of language learning. The inability to communicate represents a barrier for personal contact, healthy dialogue and mutual understanding. This is true for North American Christians who are largely mono-lingual. This is equally true, however, for Christians in other parts of the world who are hesitant to learn the languages of neighboring tribes and/or communities, thus impeding personal contact and cross-cultural witness. Further, “incarnational evangelism” demands that personal contact be fostered in a receptor-oriented environment. One such example is Insider Movements, which can be defined by their incarnational presence among a people.1 In other words, North Americans cannot depend on a Muslim’s, Hindu’s or Buddhist’s ability to speak English in order to foster a relationship. Likewise, Christians in Indonesia cannot depend on a tribe’s knowledge of Chinese or bahasa Indonesian in order to cultivate personal contact.

3. Look for ways to come alongside God’s supernatural contact so that we might confirm, affirm and disciple. Do we pray that God will use us to connect with Muslims who dream of Jesus so that we might be involved in directing them toward a biblical Christ? Do we pray the same for Hindus and Buddhists who are the recipients of Christ’s miraculous healing? As we seek to add personal contact to non-personal methods of evangelism, so too must we seek to be personally a part of God’s supernatural contact.

4. Stress the importance of personal, cross-cultural witness, whereby we maintain a presence among carefully defined unreached people groups. Personal contact among such peoples is difficult.

Non-personal methods of evangelism and mission begin to help us overcome barriers, but we cannot depend on these at the expense of personal contact. Like Jesus, we must dwell among the people he wishes to call to himself. When we do this, we draw closer to the vision of Revelation 7 where a multitude from every nation, tribe, people and language will stand before the throne “and he who sits on the throne will spread his tent (skenoo) over them” (Rev. 7:15).

Endnote

1. The October-December 2004 issue of International Journal of Frontier Missions is devoted to Insider Movements.

References

Barrett, David B. and Todd M. Johnson. 2001. World Christian Trends, AD 30–AD 2200. Pasadena, Calif.: William Carey Library.

______, George T. Kurian and Todd M. Johnson. 2001.”Part 8 Ethnosphere.” In World Christian Encyclopedia, 2nd ed. 2 vols. 30-241. New York: Oxford University Press.

Beasley-Murray, George R. 1987. WBC John, Vol. 36. Waco, Tex.: Word Books.

Carson, D. A. 1991. The Gospel According to John. Grand Rapids, Mich.: W. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Harris, R. Laird, ed. 1980. Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament. Vol. 2. Chicago: Moody Press.

Love, Rick. 2000. Muslims, Magic and the Kingdom of God. Pasadena, Calif.: William Carey Library.

Musk, Bill.1988. “Dreams and the Ordinary Muslim.” Missiology. 16(2): 163-172.

_____. 2004. The Unseen Face of Islam, rev. ed. London, U.K.: Monarch Books.

Nottingham, William J. 1998. “What Evangelism Can Mean in the Coming Millennium: Looking for the ‘One Thing Necessary’ (Luke 10:42).” International Review of Mission. LXXXVII, no. 346. July: 311-321.

Packer, J. I. 1991. Evangelism and the Sovereignty of God. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press.

Sanneh, Lamin.1989. Translating the Message. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books.

Sheikh, Bilquis and Richard H. Schneider. 1978. I Dared to Call Him Father. Old Tappan, N. J.: Fleming H. Revell Company.

Walls, Andrew F. 2002. The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books.

Wells, David F. 1987. God the Evangelist: How the Holy Spirit Works to Bring Men and Women to Faith. Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

Woodberry, J. Dudley and Russell G. Shubin. 2001. “Muslims Tell: ‘Why I Chose Jesus.’” Mission Frontiers. 23(1): 28-33.

—–

Todd M. Johnson is research fellow and director of the Center for the Study of Global Christianity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. Charles L. Tieszen is a doctoral candidate in Christian-Muslim relations at the University of Birmingham, U.K.

Copyright © 2007 Evangelism and Missions Information Service (EMIS). All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission from EMQ. Published: Vol 43-4 EMQ Oct 2007 pp.494-501. For Reprint Permissions beyond personal use please visit our STORE (here).