From Shock to Grind: Wrestling with Culture where God Has Placed Us

by Mac Iver

Iver shares how he has moved from culture shock to culture grind to a type of culture transcendence which looks only to God’s call for us.

The more I learn about culture—my culture, your culture—the less I respect it, trust it, and value it in its own right. There is something fundamentally de-humanizing about the functional “You are what you do” of the West, the sanctity of jihad and niqab (black shroud of women) in the Arab world, the tribalism of Africa, and karma’s fatalism in the East.

Each culture differs in what it ignores or denies about God’s truth in conscience, and when one has not grown up assuming this denial, it causes shock in the short term. Long term, there is a point at which shock wears off, but a kind of “grind” remains in specific areas where both conscience and culture remain non-negotiable and mutually exclusive.

No matter where one is coming from or going to, cultural interaction is inevitable, and the long-term effects of this deserve our attention. The effects of culture on the human soul are intensely personal, even intimate. As such, I do not plan to defend the opening statement here academically; neither culture itself nor our negotiation with it are entirely rational or logical. I do not plan to defend it philosophically, as it is simply too deep for this article. What I will do is tell a story, my story.

My parents became Christians soon after I was born, and I was blessed growing up in a home where God was honored, my parents remained faithful, and our needs were met. I went to college to study psychology and counseling, but was waylaid much like Saul on his way to Damascus with a new and clear cross-cultural call.

So I went to college. I studied culture and how it applies to communication.

I learned that culture serves as the social-psychological mechanism that aligns attitudes, values, and beliefs present among a given group. Culture is dynamic, even adaptive when the stakes are high enough. Culture is yesterday’s solutions applied to today’s problems. Culture is the only possible starting point for negotiating with a changing environment in the future (which starts now). Culture helps a group to integrate content, symbols, meaning, and identity over time.

There are shame and guilt cultures, individualistic and collectivist cultures, hot and cold cultures. There are no good or bad cultures; it is all just really different. Culture governs, even grants significance, to people’s behavior. Culture is a standard unto itself, a Pax Romana among competing voices.

Culture is existential. It is not a viable basis for what should be done; it is, and can only ever be, a relic of what has been. Challenging culture is like challenging the DNA of a person or the operating system of a supercomputer. Pointing out a culture’s contradictions and transforming the system are two totally different tasks.

Then I graduated. I left college figuring that culture was probably pretty important.

I got on a plane and flew to Syldavia (yes, that’s an alias). Syldavia was closed to a foreign presence like mine, although a national leader had managed to set up a Bible school and invited me to help teach English. I quickly discovered that tensions had been building between teachers and students. Four days after I arrived, the students went on strike.

Their demands unmet, a few students left the office and turned the police on me and another foreign teacher. I spent my fifth Syldavian night in a hotel in the tourist section of town. Apparently, a strike was the culturally appropriate way of expressing the sincerity of a group’s stand on a matter, even in Bible college.

That is culturally appropriate. Culture is pretty important. Shocking, maybe; but important.

I was a small fish and none of the students even knew my last name, so I just disappeared into the tourist crowd. The matter blew over, and soon I was part of an international team focused on my unreached people group. I found many handles to manage culture shock: fellowship with believers, friendship with nationals, learning personal boundaries, finding good chocolate, physical exercise, having a hobby, guarding family time, and being a blessing to others.

On my new team two members from the people group spoke with unmatched authority on matters of ministry approach. “That is not our culture” was all it took to get the sky to be green or limited accountability into a grant proposal (which failed).Sometimes, nationals disagreed with each other, which left us all stuck, gagged, and wiggling while they reached a stalemate. Tensions went underground and stayed there, as is culturally appropriate, and decision-making was often sidelined (along with ministry initiatives).

That is culturally appropriate. Culture is pretty important. I did not like it all, but it is important.

In the process of settling in and adjusting to the culture, I bought a bicycle to get around. Within ten months, the bicycle had been welded back together four times. The fifth time the frame snapped on the pot-holed roads and I decided a motorbike would be better. When traveling Syldavia by motorcycle, things happen fast, even when you are traveling at 20 mph. Everyone collectively ignores everyone else.

The rule of the road, I later found out, was “Me first.” A driver’s license cost about $8.37 and these were bought and sold at the traffic office. That explained a lot, and soon things became more predictable. I started to understand and anticipate the road’s cultural dynamics, where tolerance is a higher value than discipline and civic sense is an indefensible, irrational ethic. The culture appropriately excludes the link between power and responsibility, and simply cannot support a notion like “human rights.”

That is culturally appropriate. Culture is pretty important. I was adapting—I could handle it!

Four accidents and years later, I was due to go home. Starbucks, Pizza Hut, and smooth roads… here I come! Having lived in Syldavia for a significant period of time, I had no idea how much I had changed. I got home and went to a church picnic. Teenage girls were walking around almost naked, and no one seemed to notice. Deacons and elders were talking to each other about how they took their children to a movie about an apprentice sorcerer…and they were drawing biblical parallels.

I met friends who wanted to know, “So, how was Syldavia?” I soon realized the correct answer was, “Good, thanks! Did you catch the game last night?” Many of the churches I visited loved what we were doing but were in the middle of a $5 million building program. Apparently, $150/month was just not going to happen. Church needs to be relevant to culture, and an upper-middle-class church needs a very large, high-tech auditorium, as is culturally appropriate…everyone knows that.

That is culturally appropriate. Culture is pretty important. This was culture shock in reverse, and I wasn’t sure who I was anymore.

About eight weeks later I was on a plane to Syldavia. I again went through the phases of naïve happiness, depressing disenchantment, and creeping orientation, but much more quickly this time. I started to gain a deeper sense of orientation to Syldavia. I learned to appreciate the value of things my home culture devalued.

At home, I am what I do. Here in Syldavia, I am who I know. At home, you work hard and can make it. Here in Syldavia, you drink more tea than your body weight in a day, and no one can stop you. I learned Syldavian language, played Syldavian instruments, wrote and sang Syldavian songs, and had genuine Syldavian friends. I loved Syldavian food. I was oriented, adapted, thriving.

Now I myself was culturally appropriate… well, almost; but not quite.

Something was not quite right, and the itch continued to grow. I continued to wrestle with a mindset that I could not passively abide. People should not treat people like people here in Syldavia. People here are the chance forms of karmic seeds experiencing the effects of karmic laws they have themselves incurred.

Purity is a matter of isolation and your karma is your problem. Interpersonal responsibility is indefensible, and with it goes the grounds for interpersonal accountability. As I saw that play out in society, politics, economics, and judicial government, I could not shake a nagging sense of personal and civic violation. There was a sense of the culture grinding at the sanctity of my beliefs, at the core of who I was. It was not about suffering anymore; it was about identity.

Now there was a sense of “culture grind”—the point at which adaptation meets conscience.

What I have come to call “culture grind” is the point at which the Kingdom of God in me and the kingdom of Satan where I am clash. It is a matter of alignment, allegiance. It is the point at which adaptation turns from getting oriented into taking one’s place in the game. I can drive now—so will I drive as though you did not exist? I know which officer to go to now—so will I pay the bribe, knowing that is how he perceives honor?

Culture grind is the point at which one must choose comforting tolerance or a prophet’s inner fire. But it is more than that: it is the point at which a Syldavian’s treatment of me as an object conflicts with my own sense of humanity and I have a choice to make about who I am, and by inference, who he or she is. The culture grinds at these points because of values I flatly refuse to live without.

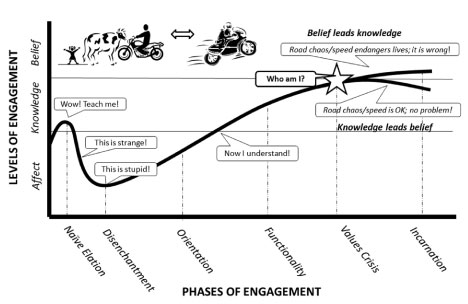

I am a visual learner and tend to think in pictures, so Figure 1 (see below) helps to summarize this process. Affect, knowledge, and belief are challenged in sequence over time as I engage with culture—both Syldavia’s and my own. For example, Syldavia says chaos on the road is okay. My culture says excessive speed is okay. Both grind on my beliefs.

We need to make the implications of this model clear: there is a difference between being functional and being incarnational. Functionality occurs when cultural knowledge keeps me oriented enough to get things done. Incarnation happens when one moves from engaging knowledge systems into engaging belief systems. Those native to the culture engage all three levels (affect, knowledge, and belief), and I am not truly “incarnate” until I also engage all three… whether I agree or disagree with the dominant perspective. This is just as true of me in Syldavia as in my own culture of origin.

Figure 1

Actually, there is a corresponding sense of conviction as Syldavian culture grinds away at my own culture’s mistaken assumptions. People mean more than what they can accomplish here, and relationships really are worth the time. There is a depth, a balance to life here that is missing in my home culture. It holds up a mirror to my face and challenges my sense of self-righteousness.

For example, one day my daughter dropped her balloon and a crowd of strangers spontaneously mobilized to rescue it from the traffic, risking their own lives without a second thought…for my daughter. How am I to connect this to the fact that female infanticide is rampant and child trafficking is a thriving business here in Syldavia? The same person who just rescued the balloon will tomorrow run us off the road. Even in appreciation, the grind remains. So then, what actually happens when the presence of God’s kingdom in me stops adapting to the ebb and flow of culture, and a Voice inside says to culture, “Here is where your proud waves stop!”

At those times, culture grind forces me to the recognition that only God is God. I am not.

This is the pivot point my world must revolve around in this Syldavian ocean. Trust in God is only theoretical until I have entrusted myself to him. I simply cannot tell the ocean waves where to stop. Like the sailor’s prayer, I often squeak out, “God, your ocean is so big and my boat is so small.” He always whispers back, “I AM so much bigger than my ocean.”

At those times, there is a living truth that people are more than what they do, that the niqab violates woman as made in God’s image, that tribal loyalty must submit to life in Christ, and that you are not left alone in your karma. I get the distinct impression that girls should dress modestly, that sorcery is evil, that MasterCard is a badly chosen master, and that a $1 million foyer is so unfathomably less important than a $1 million radio station to reach a people group.

At those times, I have stopped passively accepting what is culturally appropriate because I am absolutely certain, to the core of my being, that culture is not that important.

I don’t always live on the mountain, and an identity crisis is a hard thing to maintain. No one can live effectively in crisis. The sense of offense remains and the real question is how to live, no, thrive, in that state. Denial works as long as one is happy to live in denial for the duration. One may never get to “This is stupid,” but denial also seems to be a sure road to the “knowledge leads belief” path. Affect seems to act as a gatekeeper to full engagement in this sense, though I do not know why.

Truth is a place I have found refuge as I “believe and therefore speak.” This may leave one in the prophet’s desert chewing a sweet locust, but what about the effects of not speaking out against culturally appropriate sin?

An Asian ethnicity is majority Christian, but tribalism consistently bogs mission efforts down in ethnic politics. An African nation has linked denominational and tribal identities such that doctrine and ethnicity are one concept. A predominantly Hindu nation has churches traced back to Thomas the disciple, and yet the incorporation of the caste system has repelled millions of untouchables into Buddhism. Muslim background believers present themselves as Muslim followers of Christ without necessarily asking if one can be a Christian follower of Muhammed. Western Christians take their children to all three runs of a sorcerer’s tale and then discuss it in Sunday school.

I myself drive through a village faster than I would if my own children were near the road playing, only to dismount and share Jesus. It’s strange how culture grind has so much more power over me until I kneel and repent. In any culture, life without truth is hell.

At those times, truth itself becomes the constant reference point, the resting place.

There is an unthreatened authority that comes with truth, a law unto itself grounded in God’s omniscience. However, much like culture grind has two sides, so does truth. Truth is spiritual truth, empowered by the living God in me. It comes as a package, coupled to God’s grace. Law without grace will inevitably lead to self-absorbed pride or self-absorbed shame.

God is not at the center of either picture, and the center is where he rightly belongs. The same God who is bigger than the ocean is bigger than the sailor—bigger than his or her failures, rage, triumphs, history, or plans. Grace carries a hope and a future.

This kind of grace must have somewhere to flow or it dries up—there is a living, moving, breathing, consuming aspect to this grace that demands the dam of personal offense be broken in Jesus’ name. If the dam will not yield to the grace of the ocean’s Master, the water behind it turns black, toxic, and terribly cold. There has been more than once when the inner tension of culture grind has built up to a point where I honestly did not care about consequence, values, or life itself. There was a terrifying purity to my sense of self-righteousness in that rage.

I have come to realize that it is bigger than I am. That God-given right to be valued as a human being, coupled to a fallen nature that can twist anything into a sword, combines here to form a person whom I am truly afraid of and cannot rescue myself from. God’s grace allows me to see both what I could become and who God wills me to be in Christ, and it is overwhelming.

At those times, grace has helped me to negotiate culture grind: God’s truth flows with God’s grace, and I thrive.

There is something about being overwhelmed that is very purifying. Whatever remains after that is essential, core, enduring. Like a seed that has died and must now bear fruit by design, there is a settled sense of purpose that is unchallengeable, unthreatened, and all-consuming. It says, “Here I am, send me” with a face set like a flint. There is a hope and a future wrapped up in the DNA of whatever is left after overwhelming grace washes into a heart where emotional drive died long ago.

Out of truth come branches that bear fruit simply because that is what living branches do when they yield to the training of the Gardener. Out of grace comes a root of love that casts out fear because love casts out self, replacing it with self-in-relationship.

At those times, it all becomes a matter of yielding to the pruning of the Gardener as he nurtures the fruits of the Spirit.

Perhaps culture grind itself releases the fragrance of Christ much like a crushed flower fills a room with perfume, or the way a smoldering incense stick fills a room with fragrance. I like the way that life starts to take on a taste, a fragrance if you will, of love. I am not consuming it by any means, but I have tasted it. I still hate the obnoxious stares, the oblivious driving, and the obtrusiveness of culture in a land where I will always be a foreigner.

However, I know who I am. No; I know whose I am, and deep calls to deep in the roar of his waterfalls. He knows my name and he speaks it in a still, small voice. I am a servant of the King and a son of the Father. I am precious in God’s sight, and he loves me…and Christ in me loves you. Now I remember…that is what I came here with in the first place.

….

Mac Iver (pseudonym) earned a PhD in global leadership from Fuller. He lives in Asia with his wife and two daughters doing training and consultancy in strategic assessment and partnership development. Mac loves motorbikes and coffee. He can be reached at: m.culture.grind@gmail.com.

EMQ, Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 268-274. Copyright © 2011 Evangelism and Missions Information Service (EMIS). All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission from EMIS.