Related Articles

China— Past Mistakes and Present Dangers

Two years ago I asked a group of twenty-seven Chinese graduate students to specify three obstacles that had prevented them from becoming Christians, and to identify three reasons that prevented their fathers from becoming Christians.

Windows of Opportunity in China: New Program Trains Chinese for China

An exploration of some of the partnerships that already exist between churches inside and outside China, and an examination of how partnership between China and the West can be further intensified.

Windows of Opportunity in China: New Program Trains Chinese for China

An exploration of some of the partnerships that already exist between churches inside and outside China, and an examination of how partnership between China and the West can be further intensified.

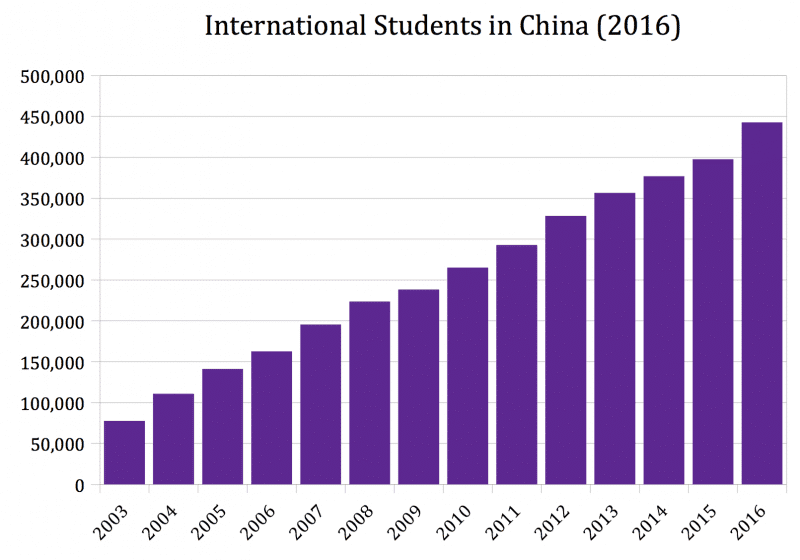

International Students in China: Who Will Reach This Vast and Strategic Yet Invisible Group?

Wearing her hijab, “Mounia” from Yemen heard the gospel and felt the love of God in our international church because of her Rwandan classmate’s invitation and her husband’s permission. Without Arabic or visa for Yemen, instead of flying to Sana’a, we walked two meters to welcome her. From a country with 0.03% evangelicals, could she take the gospel back home?

The Conflict of the Gospel and Culture in China– W. A. P. Martin’s Answer

The pages of history reveal an intense struggle among early China missionaries over the ancestor cult, Confucianiam, and emperor worship. This author discusses one controversial approach, which is pertinent to efforts of missionaries today to make the gospel culturally relevant.