EMQ » April–July 2024 » Volume 60 Issue 2

Special Article Preview

This article of Evangelical Missions Quarterly (EMQ) is a publicly accessible preview. Join Missio Nexus or subscribe to get access to all articles!

Summary: I am a Christian and a Native American from the Yuchi tribe. My family’s story reflects the challenges Native Americans experienced when Christian faith was not contextualized to their cultures. Yet I’ve also witnessed how Scripture engagement can honor cultures and bring God glory.

By Jenn Brown

My story begins where I was born – in Tulsa, Oklahoma in the south-central US. Tulsa’s history is a complex tapestry involving the descendants of Indigenous, European, and African peoples. In its modern history, it is influenced by many megachurches and was the location of one of the first televangelists.

Earlier in the twentieth century, Tulsa was home to Black Wall Street – a prosperous African American business district.[i] Before this, an oil boom earned Tulsa the title of “Oil Capital of the World.”[ii] And all of this is intertwines with Tulsa’s history in the 1830s as a place of resettlement for Native American communities.

In many ways, this tapestry is woven into my very core. From the impact of mainstream Charismatic Christianity to my family’s Native American legacy, Tulsa is part of who I am, and I am part of Tulsa.

Esau McCauley says in his book Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise of Hope, “Ethnic identity and the Christian community, a question asked and answered a generation ago, must be addressed again in our day so that our people know that God glories in the distinctive gifts we all bring into the kingdom.”[iii]

I resonate with Esau’s words. While my first identity is and will always be Christian, my second identity is Native American. I am convinced both find beautiful form and function in the kingdom of God.

The Yuchi

I am a proud member of the Yuchi[iv] tribe, one of the oldest tribes in North America. For generations, we’ve called ourselves the “Children of the Sun.”[v] I am proud to be a child of the sun. Our community originally lived in the southeast of what is now the US. In the sixteenth century, Yuchi people lived in what is now eastern Tennessee. By the next century, they migrated south establishing communities in present-day Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina, close to the Muscogee Creek people. Some groups also ventured into the panhandle of Florida.

Epidemic diseases and conflicts brought significant losses to the community in the 1800s. Those were compounded by the forced removal of native people from the southeast in the 1830s by the US government via the Trail of Tears.[vi] The Yuchi walked the trail with their allies, the Muscogee (Creek), to “Indian Territory” (present day Oklahoma).

Today, the Yuchi predominantly inhabit northeastern Oklahoma, and many hold enrollment as citizens within the federally recognized Muscogee (Creek) Nation. The Yuchi tribe is small – approximately 2,000 individuals can trace their lineage back to around 1,100 individuals documented as ethnically Yuchi by the Indian Claims Commission in 1950.[vii]

Preserving our cultural identity remains important. Yuchi people maintain long-held rituals and ceremonies, unique foods, traditional clothing, and their Yuchi language. Our beautifully complex language is a linguistic isolate not known to be related to any other language. Men and women speak distinct languages, adding to its complexity and beauty. Yet, the last known native speaker passed away in 2021.[viii]

In the 1970s, linguists worked to transliterate the Yuchi language into the English alphabet, marking a significant effort to capture and document the language.[ix] This continues to be built upon. The 1994 establishment of the Yuchi Language Project brings hope of language revival. According to the non-profit’s administrator, about 20 people have been trained to speak Yuchi as their second language. This increase in Yuchi speakers made it possible to open a Yuchi language immersion school for children up to nine years old in 2018.[x]

Christian faith is a part of the lives of more than 50% of the Yuchi tribe.[xi] Missionaries established churches and schools in the 1800s among the communities, including the Yuchi, that arrived in “Indian Territory.”[xii] Yet their engagement with communities became marred by the residential school era (1860–1978) when missionaries and churches participated with the US government in a program that sought to eradicate Native cultures and languages.[xiii]

Forsaken Cultures Needing Redemption

My great-grandmother, Nellie Staley, a proud member of the Yuchi tribe, was one of the many Native children forcibly separated from her family and placed in a Christian boarding school. She was taken at five years old and given the English name we came to know her by. Her Native name was lost.

At this institution, where smaller tribes were represented, the prevalent practice was to make students learn English by memorizing the Bible. Nellie endured a harrowing childhood marked by beatings, starvation, and torture for speaking her native language, adhering to traditional customs, donning traditional attire, and not conforming to what the school prescribed as the teachings of the Bible.

The Bible, for her, became merely a textbook as well as a symbol of abuse rather than the Word of God. It was a form of punishment rather than an invitation to have a relationship with a God who not only welcomes every person from every tribe but creates and celebrates our ethnic identities. Deep fear was instilled within her of both the holy Scripture and Christians, and she grew up grappling with the notion that her heritage made her a heathen and a sinner.

This method of Bible instruction contributed to three generations of my Yuchi family and many other Native American tribes abandoning their native languages and forsaking crucial aspects of their culture and traditions, all under the banner of spreading the gospel. In her adult life, Nellie never spoke Yuchi, and discussions about God or the Bible were noticeably absent from her conversations with her children and grandchildren.

This raises questions about the intentions of the church during that period – did they aim to civilize her, seek her salvation, or educate her about God? The consequences of this approach to Scripture engagement have had lasting impacts on the cultural heritage and linguistic traditions of the Yuchi and other Native American communities. Native cultures, languages, and religious practices were not considered. The Yuchi, with their belief in a Creator and a Spirit governing the world, were met with oppression instead of understanding and contextualization.

Being Christian and Native American

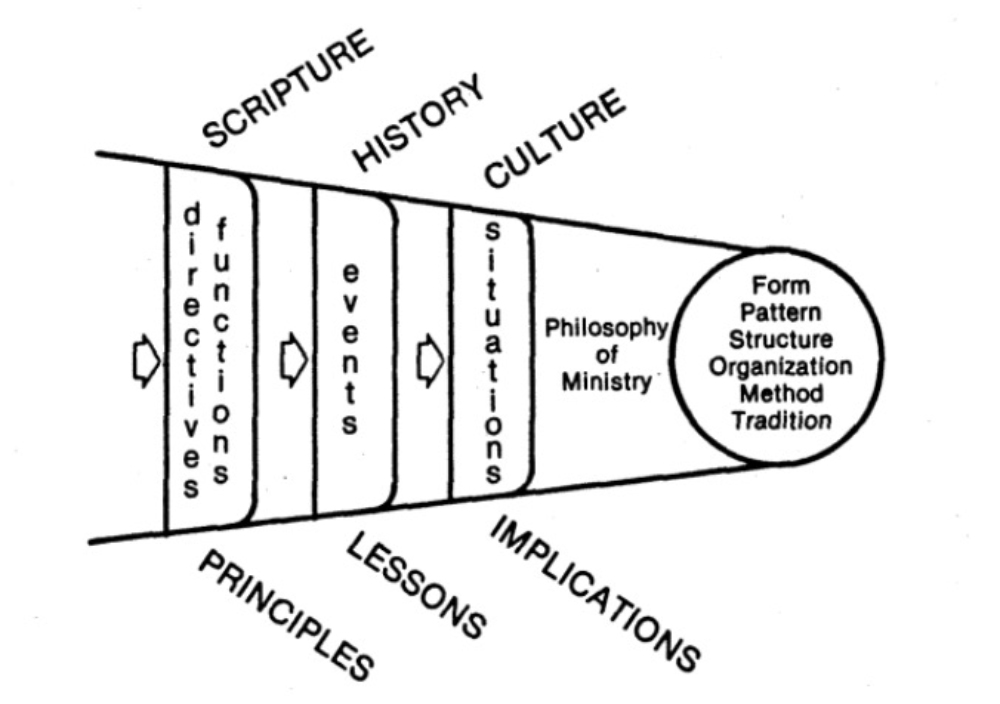

As I consider the future and my generational role and responsibility, I am reminded of the missiologist Gene A. Getz and his Three Lenses Framework (see figure 1.1). Getz argues that to develop any biblical philosophy of ministry, three lenses must be considered: Scripture, history, and culture.[xiv]

Figure 1.1 – Three Lenses Framework.

The first lens is Scripture. In the New Testament, functions and directives are frequently outlined without accompanying descriptions of form. An example of function without form comes from Acts 5:42. “And every day in the temple and at home, they did not cease to teach and proclaim Jesus as the Messiah.”

Teaching in every home is the function, but the form or how this should be done is not detailed. When the Scripture does delve into form, the details provided are consistently partial or incomplete. Duplicating the exact form and structure of ministry outlined in the Bible becomes a challenging task due to the inherent absence of certain details and elements in the Scriptural text.

Moreover, the partially described form and structure differ across various New Testament settings, making it clear that a precise replication is often impractical. While Getz calls form and structures non-absolutes in the Bible, function and principles are absolutes. A commitment to do no harm through Scripture engagement is a biblical absolute. However, countless precious souls around the world today and stretching across generations have encountered the rigidity of mistaking our forms and structures as absolutes rather than non-absolutes.

Getz makes it clear that any true biblical philosophy of ministry must be viewed through all three lenses. Scripture cannot and should not be the only lens through which we see the world. Our perspective must be consistently challenged and tested by the inclusion of history and culture to ensure our forms and structures reflect the Spirit of God’s work in building his kingdom here are on earth and using all of his kingdom to do that work.

The church and school my great-grandmother attended, while well-meaning from their own perspective, interpreted the Scripture in a way they felt was literal. Yet it was through their cultural lens. Without that perspective, they prescribed and insisted on their own forms. This led to abuse and deep generational trauma. Simultaneously, they neglected to consider the historical and cultural context of their ministry environment. They did not develop a holistic and healthy approach.

Being Native American involves embracing the belief that the world is infused with spirits, fostering a profound physical and spiritual interconnectedness. Across diverse expressions, Native Americans have consistently held the conviction that the world is inhabited by both benevolent and malevolent spirits, creating a supernatural realm.

However, a historical challenge has been the presence of superstition and fear, particularly in addressing concerns related to evil spirits. How do we navigate and overcome these apprehensions in the context of Christianity? How do we respect and renew ethnic identity into a beautifully enhanced expression of kingdom identity?

In his book, Whose Religion is Christianity, the late Yale Divinity School professor Lamin Sanneh describes what would happen if he were to send an African to Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Oxford, or Cambridge. He describes how the staff at these universities would say to this student, “‘Oh, we love multiculturalism. Wear your African dress and eat your African food, but we are going to destroy your Africanness, because we are going to tell you that everything has got a scientific explanation.’” He says that this kind of experience turns Africans into cultural Europeans.

Sanneh goes on to explain that Christianity is different. “Africans sensed in their hearts that Jesus did not mock their respect for the sacred or their clamor for an invincible Savior, so they beat their sacred drums for him until the stars skipped and danced in the skies. After that dance, the stars weren’t little anymore.” He says that Christianity helps “Africans become renewed Africans, not remade Europeans.” It respects Africanness and lets Africans remain African.

For me, Sanneh’s insights are a kingdom of heaven vision for all cultures here on earth. And for Native Americans, it shows that Christianity can respect Native Americanness and let us be fully Christian and fully Native American.

From What Could Have Been to What Is

It’s disheartening to realize that it took so long – three generations – for the ill-treatment of Scripture to be redeemed in my family and for the significance and ethical considerations of contextualization to become normative in cross-cultural Scripture engagement. What could have happened to those three generations if they could have expressed Christian faith through their ethnic identity and not apart from it?

The church’s participation in a form of ethnic whitewashing that oppressively imposed the English language and Euro-American customs caused great harm. What would have transpired if the Church had embraced the Yuchi language and contextualized its culture as it engaged them in Scripture? How could history have recorded the redemption of our language and culture?

The absence of a Yuchi Bible and the limited translation of hymns underscore the persistent gap in preserving and celebrating the Yuchi cultural and spiritual heritage. Would a translated Bible have helped generations of Yuchis come to know Jesus? What if the church had committed to a biblical version of the Hippocratic Oath, “To my greatest ability and judgment, I will do no harm or injustice?”

Despite what could have been, I am reminded of Deuteronomy 7:9 (NRSV), “Know, therefore, that the LORD your God is God, the faithful God who maintains covenant loyalty with those who love him and keep his commandments to a thousand generations.” I have experienced this faithfulness. Three generations later, I am a follower of Jesus serving at OneHope (onehope.net).

It feels remarkably redemptive to be a part of an organization dedicated to creating and sharing contextualized Scripture engagement materials tailored for children and youth in their native languages and relating to their cultural realities. Every day I see the reality of what can happen when people are engaged with God’s Word in a way that brings them honor and brings God glory.

In my own community, I take heart knowing that “yUdjEhanAnô sô KAnAnô” – “We, the Yuchi people, are still here.” God knows us. And he loves our people, our language, and our culture.

Jenn Brown (jenniferbrown@onehope.net) serves as vice president of collaborative partnerships at OneHope (onehope.net) working to build strategic partnerships and foster kingdom collaborations to reach the next generation. Additionally, she serves as a strategic advisor to next-gen global networks and movements. She is currently a doctoral candidate in missiology at Southeastern University. Her background is in entrepreneurship and ancient near east cultures and languages, with degrees from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Oral Roberts University.

[i] “Black Wall Street,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed February 1, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/place/Black-Wall-Street.

[ii] “OK Native America / Tulsa, Oklahoma: Oil Capital of the World,” The Library of Congress, accessed February 1, 2024, https://memory.loc.gov/diglib/legacies/loc.afc.afc-legacies.200003712/.

[iii] Esau McCaulley, Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2020), 166–167.

[iv] Alternatively spelled Euchee and Uchee.

[v] C. Andrew Buchner, “Yuchi Indians,” Tennessee Encyclopedia, accessed February 1, 2024, https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/yuchi-indians/.

[vi] “Stories of the Trail of Tears,” National Park Service, accessed February 1, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/fosm/learn/historyculture/storiestrailoftears.htm.

[vii] “Euchee Tribe of Indians,” Oklahoma Indian Tribe Education Guide, Oklahoma State Department of Education, accessed February 1, 2024, https://sde.ok.gov/sites/ok.gov.sde/files/documents/files/Tribes_of_OK_Education%20Guide_Euchee_Tribe.pdf.

[viii] Benjamin Din, “Pandemic threatens Native American languages,” Politico, April 13, 2021, accessed February 1, 2024, https://www.politico.com/news/2021/04/13/pandemic-native-american-languages-481081. “Maxine Wildcat Barnett,” Obituary, Smith Funeral Home, accessed February 1, 2024, https://www.smithfuneralhomesapulpa.com/obituaries/Maxine-Wildcat-Barnett?obId=29356825.

[ix] “Yuchi/Euchee (yUdjEha),” Omniglot, accessed February 1, 2024, https://www.omniglot.com/writing/yuchi.htm.

[x] “The Yuchi Language Comes Home,” First Nations Development Institute, accessed February 1, 2024, https://www.firstnations.org/stories/the-yuchi-language-comes-home/. “Yuchi Language Project,” Kalliopeia Foundation, accessed February 1, 2024, https://kalliopeia.org/grantee-partner/yuchi-language-project/.

[xi] “Yuchi in United States,” Joshua Project, accessed February 1, 2024, https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/2.

[xii] “American Indians and Christianity,” in The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, Oklahoma Historical Society, accessed February 1, 2024, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=AM011.

[xiii] “Remembering Native American Victims of US Schools,” Global Ministries: The United Methodist Church, accessed February 1, 2024, https://umcmission.org/news-statements/remembering-native-american-victims-of-us-schools/. Melissa Mejia, “The U.S. history of Native American Boarding Schools,” The Indigenous Foundation, accessed February 1, 2024, https://www.theindigenousfoundation.org/articles/us-residential-schools#.

[xiv] Gene A. Getz, Sharpening the Focus of the Church: A Biblical Framework for Renewal (Chicago: Moody Publishers, 2024), 35.

EMQ, Volume 60, Issue 2. Copyright © 2024 by Missio Nexus. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission from Missio Nexus. Email: EMQ@MissioNexus.org.

So sorry to hear the experience of your grandmother, and others like her. May the Lord bless you, your studies and your ministry and may more Yuchi come to know Jesus the Lord and Savior, to worship God, the Great Spirit