The New Shape of World Christianity: How American Experience Reflects Global Faith

by Mark Noll

Noll endeavors to place the American evangelical experience within the broader story of global Christianity.

InterVarsity Press Academic, P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515, 2009, 212 pages, $25.00.

—Reviewed by Edward Smither, associate professor of church history and intercultural studies at Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary; formerly served in France and North Africa.

The New Shape of World Christianity is the latest work by Mark Noll, one of this generation’s leading scholars on American Christian history. With compelling arguments supported by his characteristic thoroughness, Noll endeavors to place the American evangelical experience within the broader story of global Christianity. In this sense, Noll’s work is conversant with those of Andrew F. Walls, Lamin Sanneh, and Phillip Jenkins. Furthermore, it appears that Noll’s intended audience is mainstream American evangelicalism, whose members may not fully understand or appreciate the state of the present global Church.

After describing the current state of global Christianity (chaps. 1-2), Noll narrates the key points of nineteenth-century mission history (chap. 3) and explores the global impact of American missionary evangelicalism (chap. 4-5), including the alleged damage done by Western missionaries (chap. 6). Noll suggests that the American evangelical experience—marked by a high view of scripture and a commitment to conversion and evangelical activism—has served as a template of sorts for global Christian expansion (chap. 7). Prior to his conclusion (chap. 10), he attempts to support the argument in chapter 7 by showing how American evangelical regard for the world developed in the twentieth century (chap. 8), and by discussing the correlation between American evangelicalism and its counterparts in Korea and East Africa in the twentieth century.

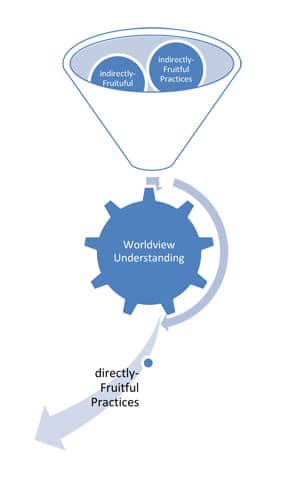

What are the book’s major strengths? First, Noll helpfully compares the American evangelical experience to that of the global Church. For instance, the parallels between Korea in the twentieth century and North America in the nineteenth are quite striking. Second, Noll carefully nuances that these parallels are not necessarily on account of evangelical “imperialism” or even the undue global influence of American Christianity. Rather, he states in the final chapter that “correlation is not causation” (p. 189). Thus, Noll affords the American evangelical narrative a healthy, objective, and humble place within the global Christian story.

I have one major critique of the book. In chapter 4, Noll seems to go too far in depicting the Jesus film ministry as a classic product sold by the American evangelical establishment (pp. 68-72). As a film version of Luke’s Gospel (that includes an invitation to embrace Christ), this work greatly parallels Bible translation. Why isn’t the present work of Wycliffe/SIL—not to mention historic efforts by Tatian, Mesrob, Jerome, Henry Martyn, and others—also deemed an evangelical product?

The American role in the film’s development and dissemination also seems to be overstated. Although Americans oversaw the making of the film and have raised millions of dollars to sustain the ministry, the work of translating and dubbing the script is necessarily that of national believers. Also, several years ago, a South African woman oversaw eighty-two dubbings of the film in just one year in West Africa—a “record” that still stands. Due to a great burden for the blind in southern Africa, this same woman and her husband developed the audio-radio version of the film. Learning of this strategy, an Arab Christian leader produced an Arabic audio version to reach North African travelers in Europe. Some of the most innovative ways of showing and distributing the film have come from Sudan, Algeria, and Egypt, where no Americans have been involved. These examples are given to show that those from the Majority World can also believe in an evangelistic tool and may be quite creative and savvy in using it.

This critique aside, Noll’s latest book should be read by church historians, North American pastors, and certainly North American missionaries seeking a healthy understanding of their own Christian history in light of the global Church.