Contextualization in a Glocalizing World

by Colin E. Andrews

Five realities we need to face as we seek to contextualize the gospel message in an increasingly globalized world that is filled with “flat cities.”

The Flat City

A one-hour flight from Bishkek over the Tien Shan mountain range (the tail-end of the Himalayas, which slices its way through Central Asia) will deposit you in the city of Osh, the southern capital of Kyrgyzstan. If this is your first trip to Osh, you might be caught off guard by the familiarity and foreignness of this place. You expect Osh to be foreign, but still find yourself in culture shock because it is in many ways more foreign than you could have expected. Some women are covered head to toe with only their eyes peeking out of their veils. A donkey pulling a cart full of cotton pulls up next to your taxi. The bazaar winds several kilometers through the heart of the city and remains the traditional place to shop as it has been for at least a thousand years. The hour of prayer is summoned in sync from the tops of hundreds of minarets. A young boy herds a flock of sheep through the city streets. You realize you are far from London or New York. But are you really that far?

If the culture shock has not thrown you off balance, then familiarity shock will. Walking behind that veiled woman is a young Kyrgyz woman who looks like she just stepped off the cover of Vogue magazine. She is the complete opposite of the other woman. Most of her skin is showing and the only veil she wears is the trendy pair of sunglasses covering her eyes. As you sit in your Soviet-era Lada taxi, a Toyota Forerunner with tinted windows pulls up next to the donkey cart. Although the bazaar runs through the heart of the city, several supermarkets, complete with scanners and bar codes, await the swipe of your credit card. As the minaret calls the faithful to prayer, you notice a jumbo-tron electronic billboard calling the working class to buy the latest pair of Nikes. As that shepherd boy winds his way through the city streets, he passes several internet cafes and cell phone kiosks. Then, the boy stops at one kiosk, reaches into his pocket, pulls out a cell phone, and pays the cashier to add minutes to it. This disorients you because at first you thought this was an example of two clashing worlds, the old and the new. But then you realize that it’s not just the cell phone shepherd boy that is disorienting. It is the fully covered woman at the internet café using the internet phone to call relatives in Los Angeles. It is the fact that many of the stores and shops in town are operated by Chinese and Turkish business people. It is that the universities are full of Pakistani and Turkish students. It is the fact that you can’t tell the difference between the South Korean businessman and the Soviet Korean restaurant owner whose name is Vladimir and can’t speak Korean. And, you chuckle as a Russian translator mediates the conversation between these two Koreans.

Osh is not some aberration in the world of urbanization. People are not just moving from the village to the city. They are moving across cultures. Some are physically moving across cultures by moving from Karachi, Pakistan, to Osh, Kyrgyzstan. Some are moving virtually across cultures via the internet, television, and cell phones. They are also being moved across cultures by the influx of foreigners into their own cities. Multiethnic communities are no longer limited to places like New York, London, and Toronto. They are increasingly emerging in places like Osh, Phnom Penh, and Nairobi. Urbanization and globalization are colliding and producing what we might call “flat cities.”

“Flat” is a term coined by Thomas Friedman in The World Is Flat, which refers to the leveling of the economic playing fields due to several flattening events and technologies. Friedman argues that the flattening of the world is radically changing politics, economics, trade, and a host of other things. This flattening of the world is now producing a neo-colonial revolution in which a flat world is colonizing itself. No longer is the West moving into the East and South. The East and South are moving into the West and into each other. Latin Americans are doing business in Asia. Asians are doing business in Africa. And everyone is online. Globalization is not just about the East and the South being influenced by the West. It involves the East and the East influencing each other, the Middle East and the East influencing each other, the South and the Middle East influencing each other, etc. The Kyrgyz are not just listening to American and British pop music. They are also listening to Turkish and Latin American pop music.

Contextualization in a Flat City

This new reality that we are increasingly finding ourselves in has massive implications for church planting and the work of contextualization. Thus far, the process of contextualization has been challenging, but fairly simple in scope. It once involved, for example, understanding the teachings of Christ in their original first-century Jewish context and then reframing those teachings into a Kyrgyz context (this is a crude and simplistic model of contextualization for the purpose of illustration). But with the flattening of cities, the task has just become a thousand times more complicated. It is no longer okay to talk about the Kyrgyz context. Outside the village, the “Kyrgyz context” is an increasingly relative term. In one sense, the Kyrgyz context in Osh is very different than the Kyrgyz context in Bishkek (the capital of Kyrgyzstan in the north) or the Kyrgyz context in the village. In another sense, there are some continuous threads in the Kyrgyz context from the village to Osh to Bishkek, and there are some flattening (global) threads in each context. Below are five realities we need to face.

1. Our contexts are no longer isolated and stationary. They are in a constant state of flux and flattening. Will they ever settle? Perhaps, but not in our generation. We need to adjust our contextualization methods so that we can hit a moving target.

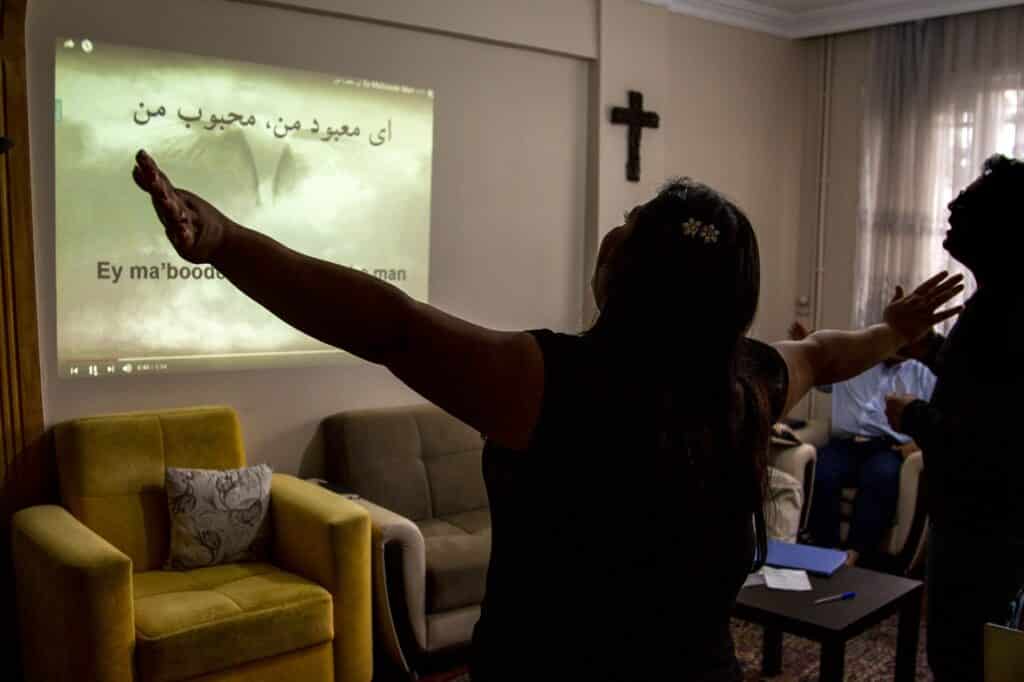

2. Indigenization is slowly fading in the memory of the pre-twenty-first century Church. The emerging Church is glocal. Therefore, the process of contextualization needs to move away from indigenization and toward glocalization. There is no longer such a thing as an indigenous Kyrgyz church, Vietnamese church, or Brazilian church. In a flat world, indigenous churches can’t exist. If we continue to focus on the indigenous church, we will find ourselves planting village churches which have no relevance to flat cities. Does this mean that the church will look the same in Buenos Aires as it does in Beirut? Yes and no. Yes, because there will and should be flat elements of the church which will look the same as cities continue to flatten. No, because the flattened Buenos Aires context will be different from the flattened context in Beirut.

3. The agents of contextualization need to shift. Western missiologists and social scientists have led the way in the development of contextualization models. While we were sleeping, however, the Church shifted from the West to the East and the South. Therefore, we need the voices of the East and South to begin to produce newer, flatter, and glocal models of contextualization.

4. We need to move away from theology and toward theologies. In a flat and fluctuating world, theology cannot be dogmatic. It needs to remain in flux as world cultures shift and change. This new reality will require agents of contextualization to start talking about theologies (plural) instead of theology (singular). An increase in theologies will increase the tension between these theologies. We need to start viewing theologies as relative maps of objective biblical truth rather than objective theological propositions. Just as a topographical map and a road map give us different perspectives of our geographical terrain, African theologies and Latin American theologies will give us different perspectives on the biblical nature of reality. Each theology will operate as a theological map that will provide one perspective of objective, biblical truth. The more theological maps we can produce, the better we will be able to perceive biblical truth. This will obviously produce tension. If you are looking for Route 66 on a topographical map, you are going to be frustrated. The agent of contextualization needs to resist the Western temptation to resolve this tension and just learn to live with it in a dynamic way.

5. We need to move away from trying to find the holy grail of contextualization models and embrace the diversity of models. No one model of contextualization will be sufficient for a flat world. Each model will contribute something new and valuable to the science of contextualization. In this sense, the process of contextualization needs to become a conversation, not a dogma. The late Paul Hiebert left us with this thought:

One must maintain a healthy skepticism toward broad theories of glocalization, since the encounter between global forces and local culture differs greatly from local community to local community and even within local communities themselves. No theory can account for such diversity. It is clear, however, that we are entering a new era in human history, that worldview clashes underlie many of the developments we see today, and that we need to understand these clashes. (2008, 264)

It is my hope that this article will spur the missiological community to not just wake up to these new flat realities. My hope is that it will act as a “conversation starter” about the future of contextualization in a flat world. Therefore, there cannot be a conclusion to this article. Rather, it must end with the simple and complex question, “Where do we go from here?”

References

Friedman, Thomas L. 2005. The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century, New York: Pan Books Limited.

Hiebert, Paul G. 2008. Transforming Worldview: An Anthropological Understanding of How People Change, Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Publishing Group.

….

Colin E. Andrews (pseudonym) has served on a church-planting team in Central Asia for the past ten years with a denominational church-planting organization. He holds a bachelors degree in English literature and a masters degree in intercultural studies.

Copyright © 2009 Evangelism and Missions Information Service (EMIS). All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission from EMIS.