EMQ » September–December 2023 » Volume 59 Issue 4

Summary: After much time and a great deal of investment, those of us who have been working in medical education missions are starting to see the fruits of our labor as African doctors graduate from their residency programs ready to go to whatever mission field to which God has called them. But how are these young men and women who have been trained, equipped, and discipled supposed to fit into the current model of medical missions?

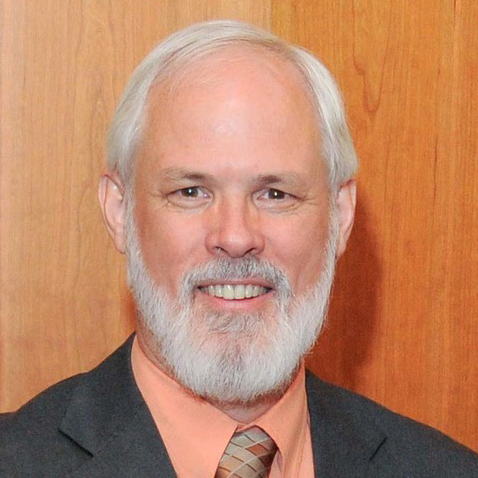

By Matthew Loftus and Bruce Dahlman

For many years, there has been a lot of interest and excitement in raising up indigenous medical missionaries in Africa to share the love of God in word and deed. After much time and a great deal of investment, those of us who have been working in medical education missions are starting to see the fruits of our labor as African doctors graduate from their residency programs ready to go to whatever mission field to which God has called them. However, we have now reached a point where the vision God imparted decades ago is starting to become hazy and indistinct.

How exactly are these young men and women who have been trained, equipped, and discipled supposed to fit into the current model of medical missions? What kinds of ministries or clinical practice opportunities should they seek out? Should they be sent through Western mission agencies, local churches, or is a different paradigm needed altogether? Should they receive the same oversight and support that Western medical missionaries receive? And (last but certainly not least) how will they be funded?

Learning From History

A corps of African medical specialists trained in mission hospitals is a 21st-century novelty. However, the questions facing medical missionaries and their proteges have been around for a very long time.

The missions movement of the last several centuries seems to grow in cycles, with an initial burst of Western-led enthusiasm initiating evangelistic and mercy ministries leading to new worshipers of Jesus. After a few years, the maturity of these believers becomes evident, along with the size of the remaining task in that geographic region or people group. Sometimes there’s also a slowdown in funds or personnel from back home, prompting questions of how to best make the recipients of missionary work into missionaries themselves.

In East Africa, for example, one can trace three general movements of missions history from the early 1800s until the late 1800s, the late 1800s until post-World War II, and post-World War II until the early 2000s, where we are at the tail end of things now. Colonial expansion in the late 1800s disrupted the natural endpoint of the first movement as European governments sought to control missionaries and their disciples so as to not disrupt European interests.

When those European interests became consumed with their World Wars and then found themselves retreating from their colonies, a rather hasty indigenization of missionary work was forced upon many – some successfully, some not so successful. The rise of the postwar movement with its emphasis on human rights, public health, vertical programs, and broadly evangelical organizations such as World Vision created many new opportunities while also restricting the capacity of others.

Historical Impacts on Medical Missions

In each of these movements, indigenous medical missions tended to get the raw end of the deal. The medical missionaries of Livingstone’s day were working with the same knowledge as other doctors in the days before germ theory. That meant that quinine and homeopathy were equally regarded.

When medicine itself became more effective and doctors became a sovereign profession unto themselves in the early 1900s, their utility towards gospel preaching became much more powerful. However, just as they were starting to get serious about medical education as a key component of service, the colonial era ended and the health systems they had helped to build for the most part became nationalized.

Theological and pastoral training endured these disruptions – you can teach people how to preach under a tree, if necessary, and existing indigenous denominational structures were far more solid. But medical education (especially graduate medical education) requires a whole set of resources and investments from the start that are harder to set in place. So since the postwar era most medical education missions and medical education in Christian institutions led by Africans has been focused on nursing schools. These investments were and remain critical. We see their fruit today in the work of many Christian nurses who are spread across the continent.

But great Christian nurses are limited if they are working under doctors with limited practical training. The collapse of many national health systems during the 80’s and 90’s – thanks to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Structural Adjustment Programs and the AIDS crisis – did not help, either.

Nowadays, many nursing schools are turning out more graduates than their countries can hire. The best medical professionals of all cadres are actively being recruited and poached to fill the ranks of siloed non-governmental organizations (NGOs). With the lack of post-graduate specialty training opportunities, doctors are being pushed to seek this training in wealthier countries that eagerly provide specialty training to fill their own (primarily primary care) work forces.

Unique Workers, Unique Strategies

We now see sharp growth in the rise of fully trained Christian doctors in Africa with a heart to see the gospel spread and health systems improved in their own countries. They are also crossing cultures to serve other people groups. Some graduates are even starting their own training programs! Our experience so far is that Western missionaries and African medical professionals work best together when they are able to complement and challenge one another as equal colleagues, collaborating in leadership responsibilities and funding streams rather than letting one group or the other be entirely in charge.

African medical missionaries have some distinct advantages to Western medical missionaries, although none of these observations are absolute. They have much greater freedom of movement within countries or regions where there are great medical needs and many unreached peoples. They attract far less suspicion and hostility than Westerners in majority-Muslim contexts. Their cultural and linguistic background is much more congruent with the people with whom they want to share the gospel. They are much more flexible in terms of their standard of living than most Westerners. Their medical and spiritual training has always been more appropriate for their context than those of us who trained in academic medical centers in big Western cities.

There are some disadvantages, too. Some of these doctors were supported through medical school by their friends and family in the hopes that they would find the highest-paying job possible and pay them back and support the education of their sibling followers. Only a few have connections to the sort of churches and support networks who can fund their work in its entirety, although a few do have this privilege and are making the most of it.

A Ugandan who wants to be a medical missionary can’t simply email his local equivalent of SIM or the IMB and get the support and training like his friend from the US or New Zealand can. Missions opportunities for medical professionals who are not doctors may be hit-or-miss among Western mission agencies, but they’re practically nonexistent for African medical professionals. And if you travel northwards enough, the anti-black racism found throughout North Africa and the Middle East means that sub-Saharan Africans go from being privileged neighbors to despised strangers.

Strategies to Energize Complementary Service

There are also many things African missionaries have in common with their Western counterparts. They need a work context in which they can use their gifts. They need emotional and spiritual support and oversight for dealing with the intense challenges of medical missions. They need to be able to provide for their families, including their children’s education. They need to build up a contextually appropriate “nest egg” for their future retirement, especially since they are foregoing a great deal of their lifetime earning potential as doctors. They need teammates and friends to work beside. And they need a permanent place to call home.

Now, God can do as he wants, and if he chooses to use a bunch of African doctors working on salaries of $800 a month to bring Arab sheikhs to Christ, I’ll be the first one to celebrate. But the vision for medical missions together requires foresight, planning, vision, and commitment. These fellow laborers have unique advantages and disadvantages that will make them a powerful force in the movement to see all peoples worship Jesus – but they aren’t superheroes, and we’ll need a strategy to work together.

First, medical missionary sending organizations need to share their best practices and ideas for training and supporting African missionaries. We need to know what has worked (and hasn’t worked) in places and institutions where other indigenous missionaries have become equal partners in missions work, like South America and East Asia. There should be clear pathways for well-trained medical professionals from African nations to join a multi-national team (or form their own) to do medical missions. We all need extra cross-cultural training and team-building to work together effectively.

Second, our resource networks should be as equitable as possible. We need to hold medical missions conferences in places where everyone can attend. African missionaries who are raising support should be able to talk to our churches back home, whether by Zoom or in person when possible. (For example, one of the authors recently worked with his alma mater to secure a grant to bring several African colleagues over to the US for an exchange rotation.)

Third, we need to deal frankly with the financial realities of our co-laborers and be willing to adapt our support accordingly. Just because some people know how to survive with a different standard of living doesn’t mean that they don’t deserve the support levels that allow them to thrive. In sub-Saharan Africa, a “401k” may refer to the number of chickens or cows they own so that they will have passive income when they retire.

We need to accept that financial obligations to loved ones are simply part of life in a place without robust social protections. Just as we would never advise an American missionary to “just trust God and Medicare” if their elderly mother back home fell ill and needed full-time care, so we should not deny African missionaries a portion of their budget every month to care for their extended family.

Fourth, we need some explicit strategies for the institutional contexts in which medical missionaries (whatever country they are from) are going to work over the next several decades. The future of mission hospitals is a challenging question in and of itself, especially when it comes to finances, but most people can agree that these hospitals still need support to build institutional capacity while also developing financial sustainability that is appropriate for their context.

Legacy mission hospitals in highly reached Christian contexts need to focus on education and training leaders for health system transformation. A country run by Christians needs prophetic voices who call the powerful to account for how they treat the poor among them. Mission hospitals in less-reached areas need support that allows them to train local believers and hire believers graduating from other hospitals to run their training programs. Government hospitals, refugee camps, and private medical clinics in totally unreached areas should be identified and teams of mission-minded health professionals should be strategically sent to them.

Fifth, we need to seriously consider how to bring the myriad of healthcare mission institutions and church health associations across the continents together. This can increase accountability and enable collaborative strategizing. When the many parts can be knit together into one body, the many resources and assets available from all quarters can be better focused. This can multiply effectiveness, especially towards reaching the least of these among us, both in health goals and spiritually. Can the various groups that facilitate short-termers, recruit faculty, fund scholarships, promote good governance, establish quality training programs, fund building projects come together, acknowledging each other’s expertise that is needed to meet collective goals?

Finally, we need to humbly ask God for wisdom and the unifying power of the Holy Spirit in our teams. We all know that even on monocultural mission teams, there are plenty of opportunities for misunderstandings, conflicts, and spiritual attacks. Adding more teammates from different cultures can make these dynamics even more challenging – but with greater challenges come greater potential for advancing God’s kingdom.

Propelling the Investment Forward

Over the last few years, it’s been a joy to see God working through diverse cross-cultural teams in sub-Saharan Africa. Our co-laborers for the gospel have acquired the technical skills and training that were previously inaccessible to many of them. Now we need to continue in the work of education while we also help recent graduates make the most of their skills as they become the teachers, leaders, and pioneers of existing and new medical missions endeavors. These African medical professionals represent many exciting possibilities for the proclamation of the gospel. To help them succeed, we also need to do what our part to fully support them in their work.

Matthew Loftus, MD, (loftus.matthew@gmail.com) teaches and practices family medicine in East Africa, where he has lived with his family since 2015. He served as program coordinator for the Kabarak University Family Medicine Residency at AIC Litein Hospital from 2018-2023. He continues to teach and practice at PCEA Chogoria Hospital. His writing can be found in The New York Times, The Atlantic, Christianity Today, Plough,and Mere Orthodoxy. Learn more at MatthewAndMaggie.org.

Bruce Dahlman MD MSHPE (bruce.dahlman@aimint.org) has served with AIM Int’l over a 28 year East Africa career as medical director Kijabe Hospital (Kenya). He helped launch family medicine as a specialty in Kenya. He was also the founding director of the Kabarak University department of family medicine. He is also on the executive team for the Christian Academy of African Physicians (CAAP).

EMQ, Volume 59, Issue 4. Copyright © 2023 by Missio Nexus. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission from Missio Nexus. Email: EMQ@MissioNexus.org.

Responses