EMQ » July–September 2022 » Volume 58 Issue 3

Culturally Appropriated Faith

Bible translation initiates a cultural appropriation of Christian faith that deepens understanding and ownership of the gospel. In unchurched regions, it introduces Christian concepts. And where a Church is already established, it furthers spiritual maturity, theological formation, and identity affirmation.

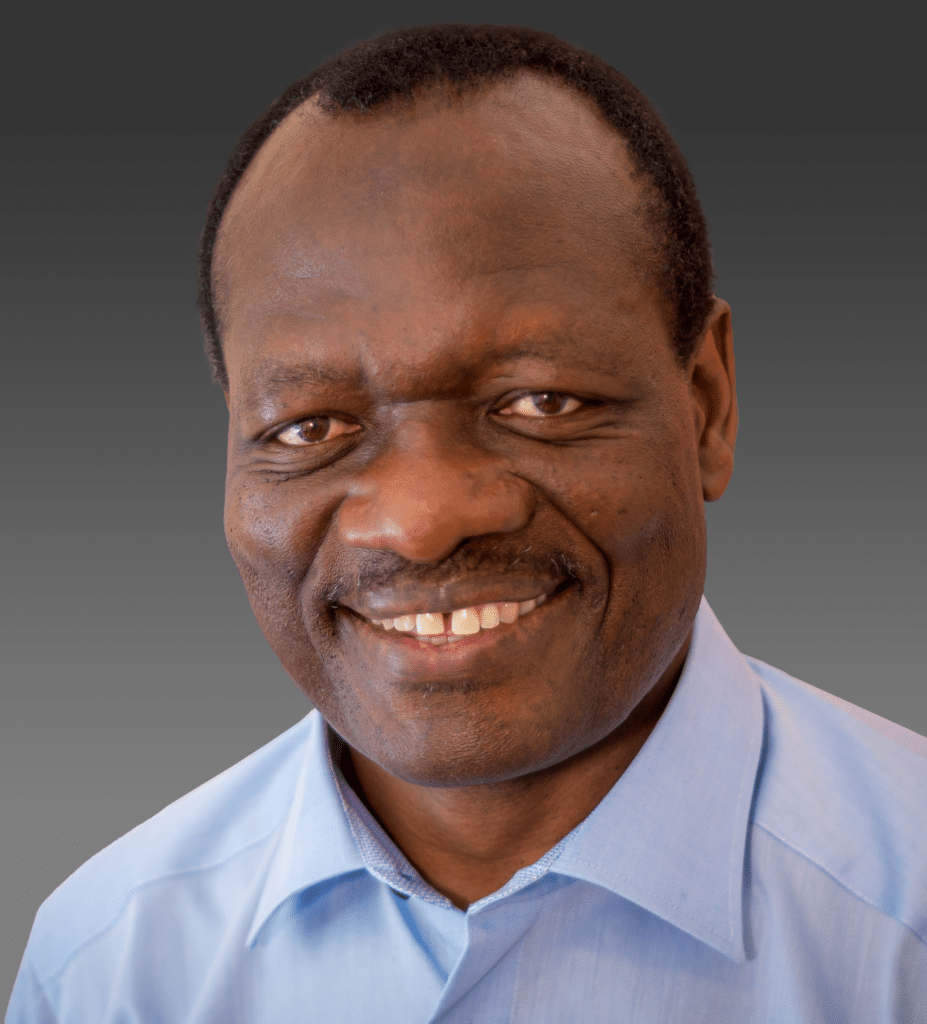

By Michel Kenmogne

We live in an exciting season in the history of missions. The Church is growing exponentially around the world, and in the span of just a generation or two, Christians in the global South and East have outnumbered those in North America and Europe. This phenomenon suggests that two centuries of the modern missionary movement have led to the near completion of what Andrew Walls calls the “missionary stage” in the process of transmission and reception of the gospel.[1]

Does this imply that parts of the Church have completed their participation in world evangelization? Of course not! Walls simply stresses that the missionary stage introduces the gospel to new recipients, producing believers who become proselytes. The next stage, according to Walls, moves believers to converts as they grapple with the intersection of the gospel and their culture, discerning how they ought to believe and live in their own context. The achievement of the second stage enables the gospel to contribute to Christianity being a global religion which is at home in every context – what Lamin Sanneh calls a “World Christianity.”[2]

History reveals that Bible translation, and the cultural appropriation of the Christian faith it triggers, are foundational to deepening understanding and ownership of the gospel.[3] Bible translation creates the appropriate conditions for people to enter an effective dialogue with God within their specific cultural identity. Meanwhile, it equips Christians to resist any attempts to domesticate the faith within a particular culture, acknowledging that Christianity must seek to culturally embody faith while avoiding idolatry of national ideals.

Bible translation creates the appropriate conditions for people to enter an effective dialogue with God within their specific cultural identity.

Today, we observe the fastest rate of production ever in the history of Bible translation[4]and an unprecedented movement of generosity[5] towards eradicating Bible poverty. We have much to celebrate! Yet, we need to ensure that our productivity produces fruit in terms of effective local appropriation of the gospel.

A keen look at the Church as it grows in the global South and East reveals important issues that should lead practitioners to rethink the practice of Bible translation in today’s world. Let’s examine some of those issues and realities and consider some ongoing efforts to allow effective appropriation of the Christian faith in every context. How might we reappraise our assumptions and practice of Bible translation to maximize the advent of Christianity as a religion that can be truly at home in every context?

The Global Church Today: Issues and Realities

Studies[6] reveal that Bible translation was the catalyst for Church growth in the Global South. Yet, the Church today is plagued with issues that suggest that the reception of the gospel has not gone below the surface level of engagement. Paul Kimbi[7] identifies paradoxes in the Church of the southern hemisphere that question the extent to which current Bible translation efforts are furthering an effective appropriation of the gospel.

Weak Impact

Kimbi writes, “One reason … the Christian center of gravity has moved to the southern hemisphere…is numerical growth …. But is there a corresponding growth of Christian values, … improved communal life or family life?”[8] It is striking to note that the increase of churches and believers does not necessarily influence the level of corruption, ethnic strife, public morality, and other ills in society. Nominalism seems to be the mark of Christianity.

Such a weak impact suggests that discipleship remains shallow, often addressing the external dimension of behavior but not diving deep enough to engage values, beliefs, and worldviews. Ultimately, this is a Bible translation issue and, more specifically, a Scripture engagement problem.

Inadequate Contextualization

“… [T]he center of gravity has moved [South] in garments (languages) from the North/West.”[9] This perception of Christianity as an export of the West reveals absent or insufficient local theologizing, i.e. native people engaging their pre-Christian heritage, confronting it where appropriate, and redirecting it in light of vernacular Scriptures in order to further a cultural Christian identity. Theological education in the global South is often an extension of whatever is thought and taught in the West. Theological institutions have not given serious consideration to biblical exegesis and mother tongue hermeneutics.[10]

These issues plaguing the growth (in quantity and quality) of the Church in the southern hemisphere will not be solved without an appropriate framing of Bible translation to address them. They challenge us to renounce any form of complacency that might come from our exuberant achievements and revisit our assumptions and practices to further a Christianity that is truly at home in all the socio-cultural contexts of the world.

The Francophone Initiative provides an example of an ongoing effort to address the issues at stake.

An Attempt to Address the Issues: The Francophone Africa Example

Around 2005, Bible agencies in Francophone Africa noted that the reported growth of the Church in that region had little to do with the advent of translated Scriptures. Though many translations had been accomplished, the scope of their use by individuals and churches was parochial or limited. Many sat on the shelves, unopened. In response, the leadership of SIL and Wycliffe in Africa, in collaboration with UBS and the Regional Fellowship of Evangelical Students, initiated a conversation with the administrative and thought leadership of the Church in the region, including prominent Francophone theologians and educators. Over the years, the group has unveiled key issues that plague the impact of Bible translation in the region, triggering the start of an indigenous response.

The State of Vernacular Use

Though Bible translation and vernacular use had been the catalyst of the sustainable growth of the Church throughout its entire history, Bible translation was not part of the curriculum of seminaries and theological institutions in Africa. To address this, African theological educators invited Bible agencies to collaborate with them to create an introductory course on Bible translation and vernacular use. To date, about 54 theological institutions and Bible schools across Francophone Africa have incorporated this course into their curriculum; the course textbook is in its third reprint.

The Impact of Theology on Faith

The group noted that academic theology – a mere copy of Western theology – and grassroots theology operate in parallel, without any interaction between them.[11] Thus ordinary believers are more often informed by African traditional religions than by Scriptural insights. Many evangelical believers revert to pre-Christian religious solutions when confronted with life-threatening issues.[12] The group concluded that the availability and effective use of Scriptures in the native languages is a non-negotiable prerequisite to foster an appropriate engagement of the Bible with African cultural realities.

Christianity and Cultural Realities

In light of the preceding observance, the group considered the delicate issue of contextualization. They acknowledged that both a denial of pre-Christian heritage and a blind adherence to it equally hinders the ability of the Christian faith to be at home in a context. Concerned about this, theologians, church leaders, and Bible translators created a framework with methods and examples of contextualization that would allow everyone to navigate this sensitive issue.[13]

An Example of the Impact of the Francophone Initiative

Cossi Augustin Ahoga is an Old Testament and cultural anthropology scholar. Years ago, Ahoga was stunned by the fragmentation of the various expressions of the Church in his ethnic group (Maxi) in Benin. The absence of dialogue and unity among them weakened their witness in a community where they were ill-equipped to engage adherents of the traditional voodoo religion. After careful study, Ahoga concluded that Western methods and frameworks for inter-religious dialogue were unsuitable for engaging the challenge of his own community.

Ahoga participated in the Francophone Initiative from its inception. Strengthened in his convictions about the use of mother tongue and translated Scripture in ministry, he took a full year to regain his confidence in his own use of Maxi. Additionally, he challenged the denomination to which he belongs to adopt the vernacular for ministry among ethnic groups.

To address the plight of the fragmented Church in his ethnic group, he began to promote dialogue based on language and identity. Testing this approach within the community, he discovered that these realities provided a common foundation for the divided expressions of the Church and reduced the barriers that had kept them separate. Moreover, language and identity provided church denominations with a common ground upon which they could engage voodoo adherents with the gospel.

Beyond his own community, Ahoga has applied his approach in other contexts and has observed its problem-solving efficiency and ability to further a relevant Church witness in each context. Reflecting on his experience, Ahoga notes[14] that Jews who have acknowledged and followed Jesus Christ do not dispose of their religious and cultural background. Rather, they call themselves Messianic Jews. In the same way, he works for a day when self-identifying African Christians will retain and use their relevant cultural values to live out their faith in Jesus Christ.

The Francophone Initiative has sought to further local agencies whereby people engage their own cultural realities to discern, chastise, confront, or affirm them as appropriate in order to truly appropriate the gospel in their context. Overall, the initiative has allowed Bible translation to move from a place of isolation to become one of the main concerns of the evangelical Church in that region. The result is that Christianity gradually finds its home in this socio-cultural context.

The above issues and realities of the Church in the global South, highlighted by Kimbi and addressed in the Francophone Initiative, have natural implications for translation practice in the twenty-first century.

Implications for Translation Practice in the Twenty-first Century

We are indeed privileged to live in the era of the greatest, unprecedented acceleration of Bible translation in history. Technology and artificial intelligence give us the promise that this acceleration could scale exponentially higher in the near future. There is cause for rejoicing! In the meantime, we must seriously ask ourselves what the result of these translations will be. The Francophone Initiative, among other realities around the world, indicates that a translation product alone does not necessarily achieve the desired impact. We should keenly discern how we engage the various factors that inform and shape Bible translation beyond the initial reception of the gospel.

In these concluding implications, I suggest some perspectives that can guide our translation practices. These implications are considered from my own perspective as a native speaker of a minority language, an observer of the Francophone Initiative, and a leader in the global Bible translation movement. In retrospect, these implications should inform the orientation and training of those who participate in the various aspects of Bible translation to enable appropriate practices in the current era of global mission.

Multilingualism and the Shifting Status of Vernacular Languages

The processes of colonization (introducing foreign languages), nation-building (adopting official languages for government and education), and today’s globalization (with rising urbanization, diaspora movements, and technological innovations) have shifted the status of the minority languages of the world. Multilingualism, translanguaging (mixing of different languages that gives rise to new varieties of language), and language loss thus become important realities. We ignore these realities to our own peril. Ignoring them could cause us to translate Bibles for communities that no longer exist, thereby turning the plight of Bible-less peoples into that of people-less Bibles.

Multilingualism invites us, in consultation with the Church and speech communities, to do the following:

- discern the Scripture needs of the community based on its multilingual situation

- identify the appropriate Scripture formats (print, oral, audio-visual), modality (mono or bilingual), and scope (portions, New Testament, whole Bibles)

- establish the mechanisms and strategies that will allow translation to improve the vitality and viability of the minority languages.

The recently developed Multilingualism Assessment Tool[15] can guide any church, agency, or community in undertaking a Bible translation with greater intentionality.

Bible Translation and the Church

As noted earlier, two centuries of modern missions resulted in the worldwide establishment and exceptional growth of the Church in the southern hemisphere. However, the Church spread around the world using foreign languages, causing a gap between the presence of the Church and the ability to engage people in the languages that are most meaningful to them. I see three issues relative to the relationship of Bible translation and the Church.

Unchecked Assumptions

In several parts of the southern hemisphere, Bible translation has not been part of the responsibilities of the Church. However, there is an ongoing assumption that church planting agencies and churches have the vision and the capacity to carry out translation on their own.[16] Denominations and church planting agencies taking responsibility for Bible translation in many countries is cause for rejoicing. However, the amount of support and capacity building they have needed cannot be overlooked. I suggest we reconsider how we seek to restore the role of the Church in Bible translation.

Restoring the Role of the Church

In response to the growing potential of the Church to participate in Bible translation, advocates are calling for a shift in leadership from Bible agencies to denominations and church planting agencies. The Francophone Initiative, the Last Command Initiative (LCI)[17] in India, and other ongoing endeavors in Indonesia provide evidence that the Church’s recognition of its responsibility and its participation in Bible translation has obvious benefits. It harnesses the potential of the Church to contribute to translation and changes the nature of its relationship with Bible agencies without suppressing it. However, qualifiers such as church-driven, church-centric, church-led vs. agency-led, etc. within the Bible translation space may inadvertently be counterproductive and distractive.

Unchurched Bible Translation Contexts

In light of the growth of the Church around the world, the default strategies and frameworks for Bible translation in the twenty-first century assume the participation of some local expression of the Church. While this is appropriate, we should not lose sight of the significant remaining contexts where no known or visible expression of the Church is present. Indeed, there may be as many as 300 communities (including about 50 Sign Language communities) still unreached.[18] Most of these unchurched communities are located in regions of the world where other religions are dominant and access is politically constrained and restricted. These communities will require cross-cultural and creative pioneering engagements that allow Bible translation alongside church planting to lay a solid foundation for the ongoing and multigenerational transformation of the communities.

The Corpus and Purpose of Bible Translation

Bible translation introduces the concepts of Christianity in regions of the world that are still unchurched or without a Gospel witness. However, where a Church is already established, Bible translation can further spiritual maturity, theological formation, and identity affirmation.

As a speaker of a minority language who first received the gospel in a foreign language, I need mother tongue Scriptures to find the categories that allow me to engage the pre-Christian beliefs, values, and worldview that shaped me in my upbringing. Translation assists in my discipling process as I seek to mature as a believer and gain the ability to discern my Christian faith and cultural identity so as to achieve harmony. However, it has been my experience that, often, the translated Scriptures achieved through the work of foreigners do not aim at satisfying such a need.

Bible translation is a major theological enterprise during which translators explore concepts and reflect on the worldview, beliefs, values, and customs of the people. Yet too often translators fail to document the theological discoveries they make when choosing how to express concepts. Such information is critical to native speakers and contributes to effective appropriation of the gospel.

For translations to advance effective discipleship and theological formation, we should reconsider the deliverables of a translation. Besides the Scripture translation itself, the work should include documentation of key theological decisions regarding issues that have worldview and cultural implications. This requirement has significant implications on the translation process, construing it as a theological exercise that effectively engages the language and the culture to accurately convey God’s Word.

For translations to advance effective discipleship and theological formation, we should reconsider the deliverables of a translation.

The Status of the Bible Translator

Though Bible translation is becoming increasingly indigenous in the southern hemisphere, its funding still largely originates from the global North. From observation, the dynamics of the interaction between the various players does not create enough space for global South scholars to release their full potential contribution in Bible translation. For this, we need to revisit some ongoing practices and reject any power play between the various players (investors, practitioners) as we all focus on the goal.

Furthermore, we need to unlock Bible translation from being an exclusive and specialized field. This will require finding creative ways that allow cooperation with all initiatives in translation, and framing Bible translation as a theological enterprise for outreach, discipleship, theological formation, and identity affirmation.

We need to unlock Bible translation from being an exclusive and specialized field.

All these considerations are non-negligible if we aim for Bible translation to effectively act as the catalyst toward a true appropriation of the gospel that positions Christianity as a world religion.

Conclusion

The quickly globalizing world of the twenty-first century tends to lock the whole of humanity into an imagined and artificial community that reduces cultural and linguistic diversity. In light of the prevailing trends, we need to recapture the deepest raison d’être, or most important purpose, of Bible translation if we want to maintain our motivation and relevance. Bible translation is the irreplaceable ingredient that preserves the essence of Christianity as a religion without a fixed language or cultural center, at home in any and every socio-cultural context.

Therefore, as we pursue Bible translation in this new era, our duty is to revisit our assumptions and practices to ensure that they enable and support the recipients of the gospel around the world in their processes to confront, adapt, affirm, and re-orient their cultural norms to allow for a true appropriation of Christianity. This will give meaning to our efforts and further the glory of God as individuals, communities, and nations flourish and enjoy full reconciliation with God, with themselves, with others, and with God’s creation.

Michel Kenmogne (Michel_Kenmogne@sil.org) is the executive director of SIL International. Born in Cameroon, Michel grew up speaking Ghomalá but was required to learn French when he started school. He holds several degrees, including a doctorate in African linguistics from the University of Buea in Cameroon. He longs to see everyone able to use the languages they value most to flourish. Michel and his wife, Laure Angèle, have five children and live in Kandern, Germany.

Bibliography and Suggested Reading

Ahoga, Cossi Augustin. “Religious extremism in Africa: we must once again evangelize Africans.” An Interview at the Forum des Médias Chrétiens d’Afrique Francophone, Lome, Togo, November 23–27, 2020. https://lafree.info/info/monde/extremisme-religieux-en-afrique-pour-augustin-ahoga-il-faut-a-nouveau-evangeliser-les-africains.

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. London: Verso, 2006.

Argyris, Chris and Schön, Donald. Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1974.

Bediako, Kwame. Jesus in Africa, 80–81. CLE/Regnum Africa, 2000.

Every Tribe Every Nation. “Who We Are: Defining the Goal.” Accessed September 30, 2021. https://eten.bible/who-we-are/#mission.

IllumiNations Foundation. “Home: God’s Word Changes Everything.” Accessed September 30, 2021. https://illuminations.bible.

Jenkins, Philip. The Next Christendom: the coming of global Christianity. 3rd Ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Kenmogne, Michel (ed). La Traduction de la Bible et l’ Eglise : Enjeux et défis pour l’ Afrique francophone. (Bible Translation and the Church: Issues and Challenges for Francophone Africa). Yaoundé: Éditions Clé, 2009.

Kenmogne, Michel. “Translation in the 21st Century: Who Needs Scripture?” International Bulletin of Mission Research 45, no. 4 (2021): 335–365. (First published August 4, 2020.)

Kenmogne, Michel and Pohor, Rubin, eds. Vivre l’Evangile en Contexte, 121–146. IF/CITAF (2021).

Kimbi, Paul. Beyond the Figures: Growing the Roots of Christianity in Africa. Cameroon: CABTAL Publishing Services, 2019.

Pohor, Rubin and Kenmogne, Michel, eds. Christianisme et Réalités Culturelles en Afrique. IF/CITAF, 2016.

Pohor, Rubin and Kenmogne, Michel (eds). Théologie et vie chrétienne en Afrique. Yaoundé, Cameroun: ADG Editions; Cotonou, Bénin: Éditions PBA, 2012.

Pohor, Rubin: “Le vécu de la conversion en milieu évangélique: questions et problèmes” in Théologie et Vie Chrétienne en Afrique, edited by Rubin Pohor and Michel Kenmogne. PBA/ADG, 2012.

ProgressBible. “Serving with Data.” Accessed September 30, 2020. https://progress.bible/data/.

Sanneh, Lamin. Whose religion is Christianity? The Gospel Beyond the West. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003.

Sanneh, Lamin. “Bible Translation and the Birth of Christianity as a World Religion.” Paper presented at Andrew Walls Lectures, Horsleys Green, UK (Wycliffe International, European Training Programme).

Sanneh, Lamin. Disciples of all Nations: Pillars of World Christianity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Sanneh, Lamin. Translating the Message: the Missionary Impact on Culture. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1989, 2009.

Walls, Andrew F. “Old Athens and New Jerusalem: Some signposts for Christian scholarship in the early history of mission studies.” International Bulletin of Mission Research 21, no. 4 (Oct 1997): 146–153.

Walls, Andrew F. The Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1996.

Wycliffe Global Alliance. “Resources: 2021 Scripture Access Statistics.” Accessed September 30, 2021. https://www.wycliffe.net/resources/statistics/.

NOTES

[1] Andrew Walls, The Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1996), 7.

[2] Lamin Sanneh, Whose Religion is Christianity: The Gospel Beyond the West (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003).

[3] Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (Oxford University Press, 2011); Lamin Sanneh, Disciples of All Nations: Pillars of World Christianity (Oxford University Press, 2008); Lamin Sanneh, Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture (Orbis Books, 1989).

[4] ETEN “All Access Goals.” By the year 2033, ETEN has identified four specific goals for attaining worldwide access to Scripture, https://eten.bible/who-we-are/#mission.

[5] The illumiNations Foundation has allowed Bible agencies to form a common front to present the Bible translation needs to high-net-worth individuals. As a result, from one year to the next an increasing generosity towards Bible translation has been observed, amounting to $40+ million donated or pledged to Bible translation over a single event.

[6] Jenkins, The Next Christendom; Sanneh, Disciples of All Nations; Sanneh, Translating the Message.

[7] Paul Kimbi, Beyond the Figures: Growing the Roots of Christianity in Africa (Cameroon: CABTAL Publishing Services, 2019).

[8] Kimbi, Beyond the Figures, 1.

[9] Kimbi, Beyond the Figures, 17.

[10] The Akrofi-Christaller Institute and Trinity Theological Seminary in Ghana constitute the exception in this regard on the African continent.

[11] Théologie et Vie Chrétienne en Afrique (Yaoundé, Cameroun: ADG Editions; Cotonou, Bénin: Éditions PBA, 2012), 54.

[12] Rubin Pohor, “Le vécu de la conversion en milieu évangélique: questions et problèmes” in Théologie et Vie Chrétienne en Afrique, Rubin Pohor and Michel Kenmogne, eds. (PBA/ADG, 2012).

[13] Pohor and Kenmogne, eds., Christianisme et Réalités Culturelles en Afrique (IF/CITAF, Abidjan, 2016).

[14] “Religious extremism in Africa: we must once again evangelize Africans”, interview at the Forum des Médias Chrétiens d’Afrique Francophone (Lome, Togo. 23-27 Nov 2020), https://lafree.ch/info/monde/extremisme-religieux-en-afrique-pour-augustin-ahoga-il-faut-a-nouveau-evangelis er-les-africains.

[15] The Multilingualism Assessment Tool (MAT) identifies four major types of multilingualism situations around the world today, provides simple guidance into the appropriate discernment of Scripture needs, and positions native speakers to be the primary decision makers. This new tool will soon be available on the EMDC website, https://emdc.info.

[16] For an excellent story that illustrates this point, read “A Madagascan Movement,” https://www.sil.org/blog/madagascan-movement.

[17] LCI is a network of several church planting and holistic mission agencies working in India that have embraced Bible translation as part of their activities in the past two decades.

[18] Ted Bergman and Maik Gibson, Study using EGIDS level 6b and above, coupled with Joshua Project criteria, reported through personal communication (2019). They judged a community to have no church if the number for Christian adherents is less than 21.

EMQ, Volume 58, Issue 3. Copyright © 2022 by Missio Nexus. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission from Missio Nexus. Email: EMQ@MissioNexus.org.

Responses