EMQ » September–December 2023 » Volume 59 Issue 4

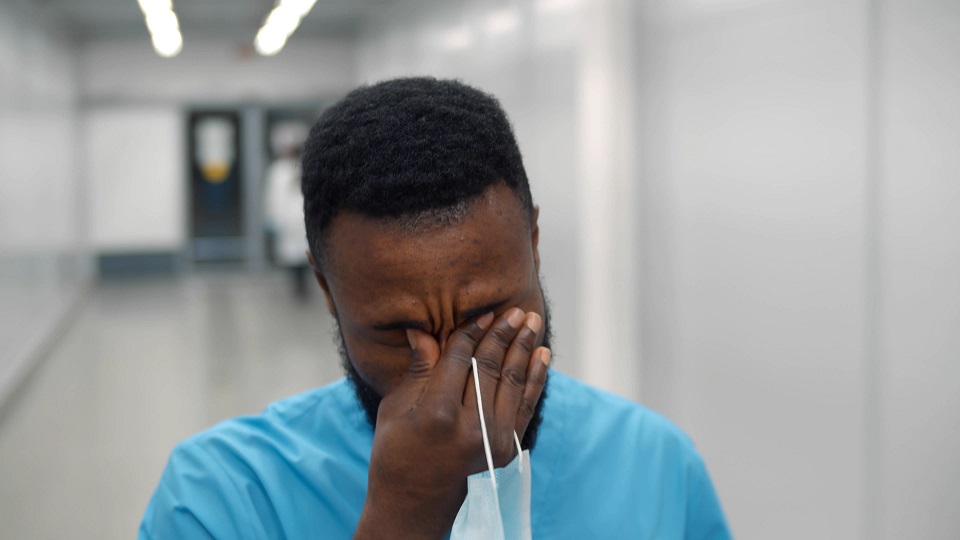

Summary: The role and experience of healthcare missionaries (HCMs) is different from other missionaries. HCMs tend to encounter death, suffering, and moral crises many times a day. Though they have experienced death and similar crises during their training or practice in their home countries (particularly if their home country is in the West), few HCMs will have seen such crises in the enormous scale found in the mission field.

By Jim Ritchie

“I can’t do this anymore,” lamented Glory,[i] who had been serving as the only surgeon in a remote region of West Africa. “Every day I wake up exhausted, dreading the line of patients I will see as I go to the hospital. Sometimes I’m running from one emergency to another, doing surgeries I’ve never seen for conditions I don’t understand, and lots of my patients die. I don’t know if it’s my fault.”

“I don’t even have the basic equipment I need,” she continued. “I thought I would be joining a team of doctors, but now I’m alone. There’s nowhere to hide. Knocks at my door come at all hours. I haven’t had a full night’s sleep or a day off in months. I wanted to do my best for the glory of Jesus, but now I don’t even want to be a doctor.”

The role and experience of healthcare missionaries (HCMs) is not better or worse, nor more or less important than other missionaries. However, it is different. HCMs tend to encounter death, suffering, and moral crises many times a day. Though they have experienced death and similar crises during their training or practice in their home countries (particularly if their home country is in the West), few HCMs will have seen such crises in the enormous scale found in the mission field.

A survey of 393 career healthcare missionaries in 2015 found that 65.8% of female and 60.1% of male participants reported moderate to severe anxiety, and 55.5% of female and 45% of male participants reported moderate to severe depression.[ii] Though reliable aggregate statistics are not yet published regarding the attrition rate of healthcare missionaries, available information indicates that the attrition rate is alarmingly high. Considering both the phenomenally powerful role of healthcare missions and the prodigious investment necessary to train and send a healthcare missionary, this attrition rate is especially disturbing.

In contrast, some HCMs serve long careers in especially challenging circumstances and are emotionally and spiritually healthy. Claire, a nurse practitioner, has served 40 years in Africa. During many of those years she cared for thousands of abused and abandoned children whose stories were heart-wrenching. Yet Claire says, “I have joy in my work every day.”

What accounts for the difference? Why do some HCMs return early from the field with serious emotional and spiritual problems, and others serve for long and healthy careers? The answer presents an important challenge to every organization that sends HCMs.

Our Perspective

MedSend partners with over 50 organizations that send HCMs. MedSend was created to assist with educational debt, but we found ourselves in a vantage point to see across the breadth of healthcare missions. Our knowledge comes from observations from formal studies, interviews with scores of missionaries, and lessons learned from partnering with counseling organizations which specialize in the care and recovery of HCMs.

Understanding the “Medical Animal”

To understand why the mission field is difficult for many HCMs, we first need to understand their mindset and assumptions. I’m an emergency physician – a child of the American medical education system. I became a member of that education system and ran a residency training program. So, I feel qualified to say: our system inadvertently sets up our young medics for burnout and spiritual conflict, especially on the mission field.

We do that in two major ways.

First, we train our medics to have an intense ethic of personal responsibility for the outcome of our patients. We train our young medics to be diligent, to ensure that everything has been done, to spend whatever time is necessary to keep up with the latest information, to review every lab, to insist on high quality care. If an unexpected poor outcome occurs, we hold root cause analysis meetings, and morbidity and mortality conferences to ferret out the cause of the error and hold each other accountable. And in many ways, this is a good thing and is one of the reasons that the Western medical system has become a standard of quality care.

Second, we train our medics to have an exceptional work ethic. Throughout training and in practice, 80-hour clinical workweeks are considered normative, and it’s not uncommon to find medics working 120 hours a week. The sense of personal responsibility becomes a mandate to ensure that every need is reasonably met before going home. Overwork and personal sacrifice become ethics of their own, and medics are lauded by other medics for their sacrifice on behalf of their patients. Again, in some ways this work ethic has enabled a very high standard of care.

Both of these related ethics were originally based in biblical teachings to love our neighbors as ourselves. But both have been mutated[iii] into values that are unrealistic and even self-destructive. Both are highly secular, with absolutely no place for God’s sovereignty in the lives of our patients. In these ethics, the medical work isn’t just the main thing, the work is the only thing. The work defines our identity as medics.

Sending the Medical Animal to an Alien World

Even in America, these ethics have led to burnout among medical professionals. In America, we have approximately one doctor for every 280 people. In many countries in Africa, one doctor serves over 20,000 people.[iv] Now, imagine training these medical professionals with American professional ethics of personal responsibility and work-related identity and then sending them to countries with 80 times the demand. And the patients are far sicker.

Now imagine that these medics are often alone, with no colleagues to share the load, to ask for consults, to share after-hours duties. Then imagine that these medics are serving in hospitals with far fewer resources. Fewer and less reliable medications, older and less functional surgical instruments, fewer functional x-ray and imaging devices. These medics feel strongly compelled to work without ceasing, to ‘pour themselves out’ for the sake of others. Because, as they so often say, “When I don’t work, people die.”

Introducing Moral Injury

Many HCMs feel that they have been unable to fulfill their mandate to help the medically needy. They feel that they have failed their patients, their sending agencies, and their supporters. Their American-trained medical ethic compels them to provide excellent care to everyone, to work until the work is done, but they simply can’t. Their patients die. These HCMs miss diagnoses because they don’t have the right labs, or the labs are inaccurate, or they simply don’t recognize the diseases. Their treatments fail because they don’t have the right medications or the meds have expired, or the nurses can’t possibly tend all the patients. They feel guilty. They feel morally injured.

Moral injury occurs when someone commits an act, is party to an act, or fails to prevent an act that violates their own deeply held moral values.[v] Moral injury is strongly associated with guilt and shame. It is also associated with betrayal.[vi] Sometimes the individual may feel that he or she has betrayed someone else, or they may feel that some trusted person has betrayed them. Moral injury disrupts our understanding of the moral framework of the world. Morally injured people may ask themselves, “Am I the moral person I thought I was? Can I trust other people? Can I even trust God?”

Healthcare missionaries go to the field expecting to save lives, relieve suffering, and serve effectively, reflecting their deeply held values. But then they encounter an unexpected world that clashes violently with those values.

A pediatrician in his first week of service found himself in the middle of a malaria epidemic, and he saw death on a frightening scale. He lost an average of 15 children a day. More children died under his care in one day than died in his entire three-year residency training. He ran from one emergency to another and was unsuccessful in his resuscitative efforts most of the time. He felt profoundly guilty and ashamed, and wondered whether he was fit to be a doctor, let alone a missionary doctor. He was morally injured.

Moral injury is like a toxin to the soul. It tends to accumulate as one experiences more moral injury. And as it accumulates, moral injury tends to cause people to distance themselves, to experience anxiety, depression, relational issues, spiritual struggles, loss of faith, loss of hope. Morally injured people are more likely to commit suicide.[vii]

It is different from PTSD. Post-traumatic stress disorder is more of an emotional disorder which follows a life-threatening event. It’s usually characterized by fear, flashbacks, and nightmares. PTSD can usually be treated effectively with medications and psychotherapy. In contrast, moral injury is less of an emotional issue and more of a spiritual issue. Moral injury usually does not respond to medications and secular psychotherapy.[viii] Moral injury and PTSD may co-exist, and tend to exacerbate each other, but they are separate entities.

Healthcare missionaries have an added susceptibility to moral injury because they practice in unfamiliar cultures. To put it simply, moral injury is inevitable in cross-cultural medicine. A culture may be defined by its set of core beliefs about the value of human life, about birth, death, understanding of money and who controls it, and who makes important decisions. Different cultures have different deeply held values. And medicine engages those different deeply held values in profound ways.

A family physician, Sean, had helped a woman deliver twins. The twins were unexpected, and the mother didn’t seem pleased. Sean reasoned that she was unhappy with a second new mouth to feed. But mom and kiddos were well, so Sean went home. The next morning, Sean found only one baby with that mom.

When asked, the local nurses didn’t want to acknowledge that there had been a second baby. Sean learned that, in their culture, when twins were born, the second twin was believed to be a demon, trying to sneak its way into the world by looking like the first baby. In that culture, the second twin was routinely killed. Sean realized that, in his mission hospital, his nurses (who claimed to be Christians) had murdered the baby during the night.

Sean was horrified. His deeply held moral values had been completely violated. He felt betrayed. He was morally injured. And upon later reflection, he realized that moral injury was inevitable for either him or the mom. Because if he had compelled the woman to take both babies home, she would have thought she was taking a demon home. The practice of cross-cultural medicine inevitably and often produces moral injury.

An insightful missionary surgeon told us, “Healthcare missions means a choice between burnout and moral injury. If I do everything that is asked of me, I will definitely burn out. That’s clear. But if I don’t do everything that’s asked of me, I will be morally injured. I will feel that I’ve failed my patients. And if I must choose, I’ll choose burnout every time, because moral injury is just too painful.”

Moral injury can come from many sources, such as: frustration over how donated money has been handled, conflict over the requirement to charge poor patients for services, dismay over the incompetence of a colleague who caused harm to a patient, guilt over having to leave the scene of an auto accident without helping due to fear of retribution, feeling betrayed by colleagues who started big work-intensive programs, and then departed, expecting the HCM to cover all the additional work.

These two large factors – a compulsion to overwork, and moral injury – are two of the most important contributors to the burnout of HCMs. Other factors, such as isolation and hostility from colleagues, surely contribute to that burnout. Most of those factors have been identified in recent studies which focused on healthcare missionaries.[ix] But if we were to identify the so called gators closest to the canoe, we would focus on these two large factors. Happily, these gators attacking God’s people can be effectively battled with God’s weapons.

Battling Moral Injury with Weapons of Identity, Community and the Vine

As described above, moral injury occurs when deeply held values are violated. But what if the deeply held values are distorted? What if the values themselves are treacherous anchors? If your map is wrong, you may think you’re lost when actually you’re in a safe place. We need to give HCMs an accurate, biblically grounded point of reference to prevent avoidable moral injury and instead promote confidence in our identity and in God’s approval.

We have said that HCMs often have an overdeveloped sense of responsibility. We think that our patient’s outcome is almost entirely dependent upon our skill and effort. When that’s our deeply held value, we can’t justify leaving the work and resting. Most American-trained medics are so convinced of the importance of our work that we have little or no place for God’s sovereignty in the fate of our patients.

But God says otherwise. Deuteronomy 32:39 is a verse that all medics (and all patients) should memorize. “See now that I, I am He, and there is no god beside Me. It is I who put to death and give life. I have wounded and it is I who heal, and there is no one who can deliver from my hand” (NASB, emphasis added). Psalm 139 assures us that our days were ordained before we were born. God is the author of life and is sovereign over the end of this earthly life.

Somehow, God is sovereign, and we have free will and experience consequences of that will. I don’t know how both are true, but the Word contains many examples of both ideas. This great mystery is, in my opinion, the most important truth for any medic to embrace. If we think we’re the medical saviors of our patients, we risk being crushed by the burden. If we realize that God is the savior (in all ways) of our patients and that we are privileged to join as his helper in the ministry of comforting, then we can justify resting. We can gratefully have boundaries to our work, and we can be confident in God’s plan regardless of the outcome.

Therefore, some moral injury, including the compulsion for overwork, can be prevented by having better, more biblical deeply held values which are not misleading. But our sound, biblical moral values can still be violated. Moral injury, as we have said, is inevitable in cross-cultural medicine. And moral injury doesn’t respond to medications and secular psychotherapy. How do we deal with the moral injury which comes from engaging this exceptionally fallen world?

Our compassionate Lord has taught us how to deal with this world. Moral injury isn’t an emotional problem. It’s a spiritual problem, and it has spiritual solutions. In our interviews and research with long-term HCMs, we have identified five regularly reported practices that help them metabolize the toxin of moral injury. And all of them are solidly biblical.

First, because moral injury involves guilt, we need to confess, repent when appropriate, and seek and receive forgiveness. Second, we can engage in the healing practice of lament. Third, we can regularly take time away, in the form of Sabbath or the longer feasts. Fourth, we can work to redeem the situation and prevent future moral injury. Fifth, we can share our burdens with grace-filled, non-judging, like-minded believers who understand our situation.

Space does not allow for a more thorough description of these practices here, but each of them is based on fundamental biblical principles. These biblical practices, when regularly and systematically and joyfully engaged, have sustained many HCMs, even in some of the most dire situations. So how do we share this God-honoring information with our HCMs?

A Program to Prepare and Sustain Healthcare Missionaries

A collaboration of like-minded individuals from several organizations, led by MedSend, have contributed to a multifaceted program to better prepare and sustain HCMs in the difficult setting of cross-cultural medicine. This program, called The Longevity Project, has incorporated several components, including a pre-field program focused on the unique challenges of healthcare missionaries, a coach-mentor program using experienced HCMs who have been trained in coaching, an annual emotional and spiritual check-up, retreats with programs specific for HCMs, and a structured short debrief.

The Longevity Project has been very well received by the participants, and we are expanding the list of components to address additional needs. The components incorporate the practices mentioned above, emphasizing spiritual solutions to these spiritually based issues. Because the Longevity Project is such a new endeavor, we are not able to report statistics on impact or outcome. However, we have received feedback from dozens of participants who have testified to the sustaining power of these biblically-based, God-honoring programs which specifically address the issues of healthcare missionaries.

Finally

Too many healthcare missionaries are leaving the field for reasons which can be prevented or improved by a better understanding of our relationship with our loving Father. The high rate of attrition is especially disturbing when we consider the profound fruit from the ministry of healthcare missions. Yet we are now able to connect healthcare missionaries with proven, God-given solutions so they can thrive, with joy, amid some of the most challenging ministries on earth.

Jim Ritchie, MD, (jim@medsend.org) served in the US Navy for 25 years as an emergency physician and residency training director. After two wartime deployments, he helped introduce the concept of moral injury in military medical personnel. He served as a medical missionary in Chogoria, Kenya for six years with terms as residency director and team leader. He now leads the Longevity Project at MedSend (medsend.org/longevity), dedicated to helping healthcare missionaries thrive in their challenging settings.

[i] All names have been changed for security purposes

[ii] M. A. Strand, L. M. Pinkston, A. I. Chen, and J. W. Richardson, “Mental Health of Cross-Cultural Healthcare Missionaries,” Journal of Psychology and Theology 43, no. 4 (2015): 283–293, https://doi.org/10.1177/009164711504300406.

[iii] We appreciate Stan Haegert’s introduction of this idea.

[iv] “Medical doctors (per 10,000 population),” retrieved May 31, 2023, from World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/medical-doctors-(per-10-000-population).

[v] Brett J. Griffin, Nancy Purcell, Kristen Burkman, Brett T. Litz, Craig J. Bryan, Martha Schmitz, Cody Villierme, Jillian Walsh, and Shira Maguen, “Moral Injury: An Integrative Review,” Journal of Traumatic Stress 32, no. 3 (2019): 350–362, https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22362. Shira Maguen and Brett Litz, “Moral Injury in Veterans of War,” 23, no. 1 (2012). “Moral Injury | Psychology Today,” n.d., accessed March 2, 2023, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/moral-injury.

[vi] Eric Newhouse, “Betrayal of Trust Can Result in Moral Injury,” Psychology Today, December 9, 2015, accessed March 2, 2023, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/invisible-wounds/201512/betrayal-trust-can-result-in-moral-injury.

[vii] Vanessa Williamson, David Murphy, Alexander Phelps, David Forbes, and Neil Greenberg, “Moral injury: The effect on mental health and implications for treatment,” The Lancet Psychiatry 8, no. 6 (2021): 453–455, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00113-9. Vanessa Williamson, Sharon A. M. Stevelink, and Neil Greenberg, “Occupational moral injury and mental health: Systematic review and meta-analysis,” The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science 212, no. 6 (2018): 339–346, https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.55.

[viii] Brett J. Griffin, Nancy Purcell, Kristen Burkman, Brett T. Litz, Craig J. Bryan, Martha Schmitz, Cody Villierme, Jillian Walsh, and Shira Maguen, “Moral Injury: An Integrative Review,” Journal of Traumatic Stress 32, no. 3 (2019): 350–362, https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22362. Vanessa Williamson, David Murphy, Alexander Phelps, David Forbes, and Neil Greenberg, “Moral injury: The effect on mental health and implications for treatment,” The Lancet Psychiatry 8, no. 6 (2021): 453–455, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00113-9.

[ix] James V. Ritchie and Patrick Woods, “Why are MedSend Grant Recipients Leaving the Mission Field? An Internal Review,” Christian Journal for Global Health 9, no. 1 (2022): Article 1, https://doi.org/10.15566/cjgh.v9i1.603. M. A. Strand, “Medical Missions in Transition: Taking to heart the results of the PRISM survey” (Christian Medical and Dental Association, 2011). M. A. Strand and John Mellinger, “Re-Imagining Medical Missions: Results of the PRISM Survey,” Evangelical Missions Quarterly 49, no. 4 (2013): 430–439. M. A. Strand and A. Wood, “That healthcare missionaries might flourish: Global Healthcare Workers Needs Assessment Report” (MedSend, 2015).

EMQ, Volume 59, Issue 4. Copyright © 2023 by Missio Nexus. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission from Missio Nexus. Email: EMQ@MissioNexus.org.

Well said Jim!