EMQ » Oct – Dec 2024 » Volume 60 Issue 4

Reimaged Missionaries

Summary: What happens when disability comes into the picture? It often results in some being left out of gospel work due to not measuring up as sufficient. In contrast to current success-driven notions of productivity and efficiency, God’s repeated pattern of working through vulnerable, weak, and fragile people calls the church to reorient how gospel workers are selected.

By Andrew K. Opie

More than 10 years ago, a previous editor at EMQ advised me to write an article on doing mission from the perspective of a person with a disability or vulnerability. At that time, I was serving with a mission agency in Bangkok, Thailand, pastoring a Thai church in crisis. As he taught me in a graduate class, he reflected with me how so little in mission is written from vulnerability or weakness. This seems to be a pattern. As David Bosch notes, mission often moves from the powerful to the powerless.[i]

When I returned from a week of classes, excited to write an article from my distinctive perspective, I kept getting stuck. I wanted to share my story of God using someone with a disability. I wanted to share my vulnerability. I wanted to share how I did not only come to solve problems and serve people, but to be served and cared for in the process. Yet, I kept feeling like I was writing: be humble like I am humble. I felt so inadequate to say what I wanted to say.

Fast forward a few years, and I began a PhD program. In my introductory class to the study of mission, I read a lot of pages from experts in the field. Academic writers write with authority to make their argument. I felt two aspects of power taking place. One was an implicit sense of how authoritative writing comes across, and the other was that speaking of mission from the margins, the periphery, or the underside of history was neglected.

Our first assignment was to reflect on something from the literature and give a brief presentation to the class. I chose to reflect on something not found in the literature, which was the lack of a discussion of mission from weakness or vulnerability. This reflection on gospel work and the role of weakness took me years. It unsettled ideas I had about missionaries being heroes in the church.

Are Missionaries Heroes?

In my formative years, my dad read missionary biographies to me. I remember stories like God’s Smuggler by Brother Andrew in particular, but others also contributed to my ideas of what it meant to be a missionary or what I now refer to as a gospel worker.[ii]

Growing up, my family supported missionaries in places like Columbia and Papua New Guinea, so I learned about special people who go to distant places to minister the gospel. When we visited with these people, they were put on a pedestal in my mind. Maybe this was inadvertent, or maybe this came about due to the church’s sensibility that missionaries were the elite among Christians.

With this in mind as I grew older, when a cute girl in my youth group suggested that I go to camp, at least for the “missions night,” I convinced my football coach to allow me a day away from summer practice in getting ready for the fall season. If the girl thinks missions night is the best night, then I made sure I was going to be there.

I remember enjoying the camp and feeling the presence of God. That night, during the service, the speaker gave a compelling message for mission work. To make a long story short, I felt compelled by the Spirit of God to acknowledge a calling to be one of those who would be sent to share the gospel in distant places. In hindsight, I wonder how predisposed I was to being a hero.

Some reflect on the way that foreigners come to places with the poor and desperate as places where these people get elevated to a special status. In terms of how this plays out on the continent of Africa, Tite Tiénou asks, “is Africa good only for promoting outsiders to hero status.”[iii]

These observations extend to anywhere that missionary work goes in which the missionary becomes the specialist or one with elevated status. By no means are all gospel workers treated this way or do all act this way, even inadvertently. However, even some who do not take seriously the power dynamics of the rich and poor or the “American” and those in need may unwittingly perpetuate the missionary as a pedestaled hero. Why does this continue to be the case?

At 17, I said yes to a missional calling from God. A short three years later when I lost my eyesight, I wondered if God was still calling me into missions. At this point, I did not know all that had been done to strategize ways to evangelize the world.

As a teenager, I was not familiar with the watchword of the student volunteer movement dating back to 1886’s North Field camp meeting, “The Evangelization of the World in this Generation.” I had not been at the Wheaton Congress in 1966 which ended on a high note stating the evangelization of the world in this generation would take place.

I did not know Renee Padilla’s challenge to current mission practice in his address to Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization in 1974. Padilla observed concerns with current practice seeking to reach the unreached. In his essay, he noted a convergence of best practices along with computerized mapping to target where the gospel needs to go. In reaction to what he found in a mechanized mission activity, Padilla claims, “The real problem is to produce the greatest number of Christians at the least possible cost in the shortest possible time.”[iv]

I had not become steeped in success-driven ways of measuring gospel activity by who is yet to be reached.[v] Yet if I’d known about the target to reach the unreached, I may have seen myself grow into a worker who could get a lot done in a short time.

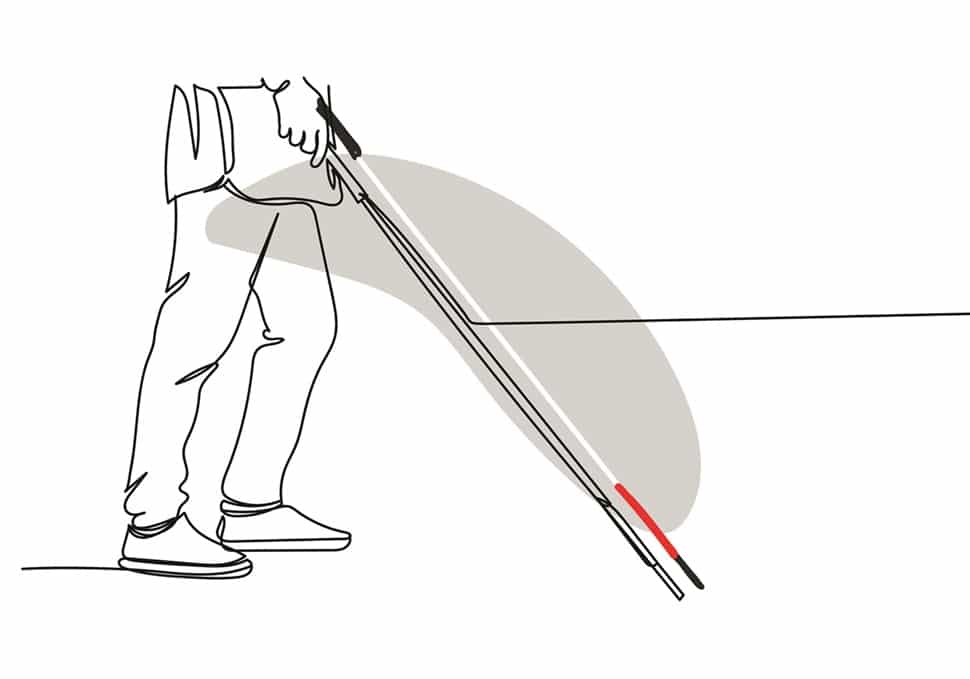

All of that changed when my visual impairment limited my capacities and capabilities. I lost my eyesight due to a genetic condition called Leber’s Hereditary Optic Neuropathy. Blood stopped going to my optic nerve rendering my nerve basically dead. My eye worked normally, but the picture did not get to my brain.

Was My Calling in Trouble?

I thought I was broken and God’s calling on my life was in trouble. I thought my disability was something needing fixing or curing. I could not imagine how I would fulfill what God put in front of me. This was about 20 years before Benjamin Conner’s 2018 book entitled Disabling Mission, Enabling Witness. In this book, Conner disables what it means to work in structures or systems that only want those with abilities to accomplish things.[vi]

Disabling speaks to how to disentangle ableist norms in the way people speak about mission, mission organizations, churches, and what is expected of people who participate in Christian witness. Without texts like Conner’s to help me, I had to wrestle alone with what it meant to no longer be the picture of a self-sufficient, charismatic, able-bodied man.

Let me be clear, the church does not overtly say this is the kind of person we are looking for. But in subtle ways, I knew I was not what people wanted in a gospel worker. Before encountering barriers to schooling, training, or sending into mission, my disability left me feeling inadequate.

In losing my eyesight, I could not drive myself to church, work, friends’ houses or to any other activities. I went from independence to depending on others for help. I felt needy and unfit. Several terms speak to disability over the years such as unfit, invalid, handicapped, or abnormal.

Invalid is an interesting term. It became easy for me to go from feeling valid to no longer feeling valid due to losing my eyesight. Saying a person is an “invalid” carries connotations that a person is not a valid human being. Feeling this, I thought I was strange and knew people treated me differently now. Some of my friends no longer knew how to be my friends.

My blindness sticks out as a visible marker now. I wondered how people viewed me, not to mention how I viewed my own worthiness.[vii] I wondered how I could be useful to God because I thought God uses people who have something to offer. I felt like my ability to be something for God had been taken away.

Who is Worthy of Time and Resources?

In many ways, ideas of productivity lead people to think life is about what people produce. Brian Brock connects disability to a world mechanized for efficiency.[viii] In this world, productivity is celebrated and beauty highlighted. Yet those with disabilities are left behind as they do not measure up to expectations of an industrialized society valuing the beautiful, creative, or productive.

Similarly, mission organizations racing to do the most in the fastest amount of time suffer from complicity with how those who do not fit into pictures of who accomplishes evangelistic goals for a return on investment. This results in the church falling victim to cultural expectations of efficiency and order in a society that values success.

Additionally, John Swinton speaks to issues of efficiency and accomplishing what a person can in a fast pace in his work, Becoming Friends With Time.[ix]In understanding time as a resource along with what someone earns in a space of time, Swinton underscores how people dependent on others for care become a question of resource allocation.

Swinton notes how some question if people with needs are worth time and money. The rise of eugenics in early 1900s gave birth to societies that determined some to be a drain on national resources.[x] Still these questions persist in issues of caregiving. These are questions I wrestled with as I lost my eyesight. What am I worth to others if they have to help me? Am I a drain on their energy?

I felt sorry for myself. I wondered how God would use me according to his calling on my life. This was my bargaining chip with God. Over a few months of coming to terms with losing my eyesight and how that eclipsed my imagination of how I could fulfill all God had for me, I began crying out to God.

One evening at a worship service, I began praying to God emphasizing the need I thought I had for healing. I thought, “I cannot do what you want me to do unless you fix me.” But then during this prayer, I felt in my heart a nudge to say, “or you will have to use me in spite of this.”

This nudge did not come from my own thoughts as that was the last thing on my mind, yet God unlocked something in me to move into his service with or without all the external competencies. Over the next 20 years, I learned to rely on texts where God’s power would be evident in cracks of an earthen vessel.

Does God Disable?

I related to Moses, God’s spokesperson who struggled with a disability of speech. Later, Jacob became a role model. He was one of Israel’s patriarchs who encountered God and left with a limp. Frances Young details this episode as God’s disabling Jacob. In Jacob’s brokenness, God demonstrates his blessing. For the rest of Jacob’s life, each step he took reminded him of God’s touch on his life.

As I consider Jacob, Moses, or even Paul, I wonder why society asks for everything to be ideal in our bodies and natural faculties when God routinely works with people who are misfits.[xi]In my own life, I see brokenness as a place to yearn for God’s presence.

Jacob’s story illustrates not only God working through a person with frailty, but God disabling. This goes against ideas of disability being a mark of sin or a tragedy of fallenness. Rather, God acts on a particular human for a particular reason.

Sometimes disabilities come from God; sometimes from simply living in this world. Nevertheless, Jacob’s story complicates easy narratives on why disability is here or what disability says about a person. Additionally, Jacob’s plight demonstrates a life where God’s grace shines in Jacob’s so-called lack.[xii]

So why do we imagine gospel workers as heroes or as people who produce a lot?

In terms of gospel work, the church often views people in terms of what they can accomplish. When I lost my eyesight, I too wondered what I could offer God.

How Do We Make Room for All?

Frances Young highlights ideas of the value of productivity as based in European or North American success. In contrast, she notes her son, Arthur, with severe cognitive impairments, offers value in simply being as he enjoys the world around him. Further, Arthur reciprocates love and grace displaying values uneasily quantifiable.[xiii]

Giving and sacrificing to care for people who need others has intrinsic value. Disability offers the church a chance to understand the body of Christ. Dependence within human frailty teaches reliance on God.

In my story, I discounted myself and also encountered discrimination in being overlooked at best or dismissed, disregarded and discarded as worst. In understanding the challenges of gospel work and disability, I found that I needed help. However, needing help does not mean I am helpless or useless. I gave of what I could while receiving help along the way.

In fact, this sounds like the picture painted through biblical imagery of family or the body of Christ. As I navigated Bible college, youth ministry, and then six years of work in Bangkok, I found God’s grace overflowing in whatever areas my life lacked. I could say as Paul said, whenever I am weak, I am strong (2 Corinthians 12:9–10).

I am grateful that God never invalidated his call on my life when a debilitating condition of blindness affected my vision. God knew what would happen, and he was faithfully present with me and worked through me.

What might happen if the church reimagines the whole church participating in gospel work and not only a special few who accumulate the glory and prestige. What if not only those who seem whole participate? By realizing that all humans are frail, fragile, and creaturely in relation to almighty God, we make room for more than just the right kind of people. We clear barriers for all people, whether so called abled or disabled, to serve in God’s mission.

Rather than imagining gospel workers as heroes, let’s re-envision gospel workers as vulnerable people willing to be used by God. This is why I love DT Niles description of Christian witness. He says, “Mission is one beggar telling another beggar where to get bread.”[xiv] As gospel workers, we must remember our encounter with the gospel and cultivate an ongoing disposition of humility, dependency, and yearning for God.

God Works Through Vulnerable People

In gospel work, ideas of perfection and performance seep into our imagination. I experienced this myself as ideas of normalcy and capacity crept into my own thinking. Organizations with structures built around order and efficiency can be even more vulnerable. Even though, I know God works with all and through all in a biblical sense, theology and practice conflicted in my heart.

Yet God drew me to his pattern of working through frail, vulnerable people. Rather than discounting myself or letting others discount me, I held close to God. If God can use Moses to be his spokesperson when Moses does not speak well, God could use me. If God could use Jeremiah who contended he was too young, God could use me. If God could use Paul with his numerous weaknesses detailed in 2 Corinthians, God could use me.

I hold onto passages like 2 Corinthians 12:10 (NIV), “For when I am weak, then I am strong.” Now, I interpret Paul as saying, when I am weak, God is strong, or when I am weak, the gospel is strong. This flips how we consider who is able to serve in gospel work.

My reflections call the church to a spirituality and mission that draw on moving slower. Instead of measuring how the gospel can go the farthest and fastest, what if goals focus on establishing faith that lasts? Instead of looking for gospel workers who become heroes, we might remember Paul’s words about a person who plants seeds and another who waters, but God is the one who brings growth.

If we understand gospel work as belonging to King Jesus, the subject of this grand story, then we free ourselves from finding ways to make the gospel do what we want it to do. This freedom from feeling like the work is up to us and belongs to us allows us to see God work through all and for all. The gospel does not belong to us. This reorienting brings gospel power into focus and places our human powers as nothing relative to God’s power. With this in mind, mission flows from God through broken, fragile people.

Andrew K. Opie (aopie@lifepacific.edu), PhD, serves as director of the Center for Global Pentecostal Studies and Practice at Life Pacific University. His dissertation, “Witness and Weakness,” is a trialogue between disability, mission, and Bible. Andrew brings a first-person perspective to disability theology as a person with blindness. He served in Bangkok, Thailand with Foursquare Missions International in church planting and leadership formation. Andrew has been married for 20 years and has two children.

[i] David J. Bosch, Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1991).

[ii] I choose to use gospel worker to highlight that God calls all of us to witness and to disentangle ideas of missionaries as special categories of people. Nonetheless, I acknowledge complexities for those who do gospel work in other contexts.

[iii] Tite Tiénou, “The Training of Missiologists for an African Context,” in Missiological Education for the 21st Century: The Book, the Circle and the Sandals, ed. J. Dudley Woodberry, Charles Van Engen, and Edgar J. Elliston (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1996), 93–100.

[iv] C Rene Padilla, Mission Between the Times: Essays on the Kingdom (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1985), 17.

[v] I wonder how we determine when a person is reached, and when a group is reached since groups are dynamic and continually being filled with new young members of the group.

[vi] Benjamin Conner, Disabling Mission, Enabling Witness: Exploring Missiology Through the Lens of Disability Studies (Downer’s Grove: IVP Academic, 2018).

[vii] On disability language evolving over time, see Corinne Kirchner, from “Survival of the Fittest” to “Fitness for All” to “Who Defines Fitness Anyway?” in Disability as a Fluid State 5 (Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited, 2010), 131–57. Irving Goffman describes disability as a stigma as analogous to the branding of a slave. Irvin Goffman, Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1963).

[viii] Brian Brock, Wondrously Wounded: Theology, Disability, and the Body of Christ (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2020).

[ix] John Swinton, Becoming Friends of Time: Disability, Timefullness, and Gentle Discipleship (Baylor: Baylor University Press, 2016).

[x] Most notably, the Nazi government in Germany codified eugenics into law and referred to people with disabilities as “life unworthy of life.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “‘Euthanasia’ Propaganda,” in State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda, accessed July 31, 2024, https://exhibitions.ushmm.org/propaganda/euthanasia-propaganda.

[xi] “Disability, then, [as] the attribution of corporeal deviance – not so much a property of bodies as a product of cultural rules about what bodies should be or do.” Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), 6.

[xii] Frances M. Young, Brokenness and Blessing: Towards A Biblical Spirituality (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2007).

[xiii] Frances Young, Arthur’s Call: A Journey of Faith in the Face of Severe Learning Disability (London: SPCK Publishing, 2014).

[xiv] DT Niles, That They May Have Life (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1951), 96.

EMQ, Volume 60, Issue 4. Copyright © 2024 by Missio Nexus. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission from Missio Nexus. Email: EMQ@MissioNexus.org.

Responses