EMQ » July – Oct 2024 » Volume 60 Issue 3

Intercultural Partnership

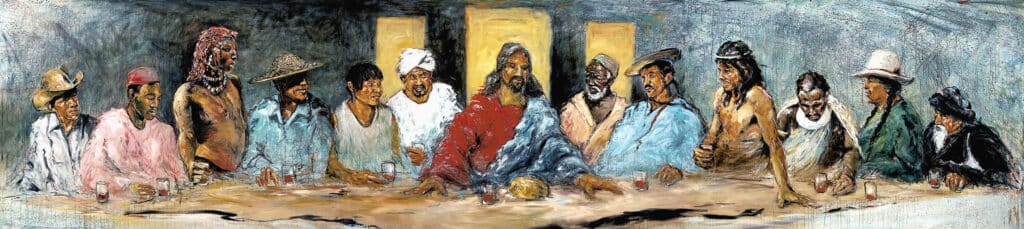

Summary: When an extended family gathers together from far and wide to share a feast, who sits at the head of the table? Traditionally, it is the father. However, what happens in this metaphorical scenario when instead of the Heavenly Father sitting at the head, that place is usurped by a culturally dominant sibling who views themselves as superior to their Majority World brothers and sisters?

By Jessica Udall

In 1994, the Kenyan intellectual and theologian Dr. John S. Mbiti asked a series of crucial questions of the Western Church:

“We have eaten with you your theology. Are you prepared to eat with us our theology? … The question is, do you know us theologically? Would you like to know us theologically? Can you know us theologically? And how can there be true theological reciprocity and mutuality, if only one side knows the other fairly well, while the other side either does not know or does not want to know the first side?”[i]

These questions remain relevant, today. Continuing with Mbiti’s metaphor of a shared meal, I ask: When an extended family gathers together from far and wide to share a feast, who sits at the head of the table? Traditionally, it is the father. However, what happens in our metaphorical scenario when instead of the Heavenly Father sitting at the head, that place is usurped by a culturally dominant sibling who views themselves as superior to their Majority World brothers and sisters.

For this to happen, as it often does, the culturally dominant sibling must be under the sway of one or more false presuppositions, all of which collude to create a phenomenon I have long observed. I call it resource righteousness. I define this as the belief that the group with the most power, infrastructure, or resources must necessarily have the best theology and should be listened to more closely and given leadership over all things with which they are involved.

The Presuppositions of the Resource Righteousness Approach

The fallacy of resource righteousness springs from several deep-seated, often unconscious, biblically-contrary presuppositions which kill true intercultural partnership in mission. These presuppositions on the part of those who are culturally-dominant include, but are not limited to, the following:

Historical Centrality

The head-of-table sitter has likely been taught a Eurocentric story of Christian history. It contains elements of the truth, yet often leaves out more than it includes. For example, Samuel Deressa seeks to set the record straight by reminding his readers that “Christianity existed in Africa beginning early in the patristic period (perhaps even before then in the cases of Ethiopia and Egypt), and that Christianity existed in Asia before the arrival of western missionaries.”[ii] Christianity continues to grow across both continents until the present day, while Christianity in the West is in decline.

It is no longer expected that the majority of theological reflection would come from Palestine (because of the theological contributions of the Apostles) or North Africa (because of the theological contributions of Augustine and his contemporaries). In the same way, it should not be expected that the majority of theological reflection should come from an area of the world where church membership and growth is decreasing.

Instead, we must remember that the gospel has been present globally (while certainly not in every people group) for a large swath of Christian history with ebbs and flows according to the Spirit’s will. This can encourage those around the table to view each other as equal teammates in theological reflection and disciple-making without hierarchy. Today, the mission of God is taking place from everywhere to everywhere, from the people of God to the not-yet-people of God. The global church can only function as a healthy team of disciple-makers if we truly value each other’s contributions.

Aculturality

Those who hail from culturally dominant backgrounds are often under the mistaken impression that their theology is acultural. Therefore, it is qualitatively different and superior as compared to the cultural theology practiced by those from other (majority world or minority) backgrounds. This way of thinking leads to an often unconscious cultural hegemony in theological practice. It requires the conformity of Christians from other cultures to the dominant cultural norms if they are to gain theological approval and acceptance in the Global Church.

Keon-San An describes this reality as a “theological monopoly [which] is prevalent in many different places in the world.” It assumes that those from (or at least trained in) the West should do the talking and the teaching, while others should do the listening and the learning.

According to An, mutuality does not exist in this model, since “genuine interdependence is possible only when the entities in a relationship are independent. A healthy relationship is not one-sided – the ‘give’ of one side and the ‘take’ of the other side – but reciprocal—the ‘give and take’ of both sides.”[iii]

When exported without reciprocity or the possibility for balancing dialogue, Western cultural norms are noticeably discordant in many other cultures. This can hinder evangelism and discipleship efforts because of the perception that the gospel is a foreign import.

People from other cultures hearing the gospel for the first time or those deep in a discipleship process with a strong Western slant who become disillusioned may both confuse rejecting the gospel with rejecting the Western trappings and framings that have clung to it. This can happen because of a resource righteousness that refuses or is blind to the need to contextualize because of a spiritual superiority complex.

Theological Oligarchy

When resource righteousness is at play, it condones a theological oligarchy that ensures the governing of the many by the few according to the cultural norms, preferences, and emphases of the few. This leads to theological reflection that majors on a certain small context – its needs, pressing issues, and perspective on the rest of the world.

This kind of theological consideration is often not reflective of the contexts of most at the table. It therefore misses relevant areas and issues that are in need of robust theological reflection and missionary praxis in the multiple contexts where the gospel finds itself.

Majority-world Christians need to be given seats at the table of theological conversation. The demographics of modern day Christians are more accurately represented by a young “woman living in a village in Nigeria, or in a Brazilian favela”[iv] than an elderly man from Britain or the United States. Correspondingly, “Third World theology is [more] likely to be the representative Christian theology.”[v]

This is not to suggest that the theological reflections of elderly British and American men are unneeded. Rather, this suggests that they are insufficient for the numerous diverse contexts and contemporary challenges and opportunities facing the global church.

To face challenges with resilience, take opportunities with wisdom, and proclaim God’s Word with relevance in a globalized world, we must theologically reflect together for the co-edification of the diverse body of Christ. This means allowing the table fellowship of believers from around the world to reflect global faith demographic realities. A token non-Westerner invited into table fellowship is not enough. The table needs to be crowded and even expanded to include many from diverse cultural backgrounds that reflect the diverse global Church itself.

Lack of Blind Spots

When someone from a dominant culture sits in the head-of the-table chair, their blind spots become barriers to the gospel in other contexts because those spots are not examined with the light of the gospel. These blind spots have repercussions even in the dominant culture of the head-of-table sitter. However, they can turn into disastrous chasms in other contexts where the area of the blind spot is of larger cultural concern.

Neglecting to look at the theological and missionary praxis blind spots that come from a missionary’s cultural context props open the door for shallow religion and syncretism to creep into the lives of their disciples from other cultures. Cultural blind spots are unconsciously transmitted wherever resource righteousness and cultural superiority are found. This occurs because meaningfully engagement with contextual concerns is overlooked and thus an opportunity for mutual theologizing and together discovering God and his truth anew in a new cultural context is missed.

Wealth as Purely Asset

Christians from a dominant culture can be understood as being wealthy in a broad sense. This could mean that they have more in terms of material possessions. It could also be understood more intangibly. For example, it could mean having more worldly Christian clout with regard to influence, prestige, global and domestic connections for publishing and jobs, infrastructure, availability of books or online resources, etc.

Scripture is replete with warnings regarding the pitfalls of wealth of any kind. Wealth tends to deceive us and make us lose touch with God, as well as with our humanity and others’ humanity. While those who are not wealthy have other temptations, they often have clearer thinking in these areas.

Using table imagery, James strongly cautioned the Church not to be over-awed by rich people or show partiality towards them to the detriment of those who have less wealth:

“For if a man wearing a gold ring and fine clothing comes into your assembly, and a poor man in shabby clothing also comes in, and if you pay attention to the one who wears the fine clothing and say, ‘You sit here in a good place,’ while you say to the poor man, ‘You stand over there,’ or, ‘Sit down at my feet,’ have you not then made distinctions among yourselves and become judges with evil thoughts? (James 2:2–4, ESV).

James goes on to defend his bold accusation. He makes the following assertion that echoes Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount: “Listen, my beloved brothers, has not God chosen those who are poor in the world to be rich in faith and heirs of the kingdom, which he has promised to those who love him?” (James 2:5).

Though James reminds them that it is the rich who oppress them and make their lives difficult, the believers “have dishonored the poor man” (James 2:6) by assuming that he was not worthy of a legitimate seat at their table. In the same way, those who have a sense of cultural resource righteousness dishonor those who come from cultures with less material or intangible wealth when they equate that status with a lack of theological vitality and depth. In reality, the opposite is more likely to be true of these cultures.

The Alternative Approach: the Global Theological Table Fellowship

There is an alternative to resource righteousness. I call it the global theological table fellowship. For this alternative to be viable, a person sitting at the head-of-the-table sitter from the dominant culture must instead sit amongst his brothers and sisters around the table.

The head chair needs to be left for the Heavenly Father of them all. This posture also requires space to be made for those who come from cultures which appear to have less in worldly terms, knowing that God’s grace is not bound by appearances. As 1 Samuel 16:7 says, “For the Lord sees not as man sees: man looks on the outward appearance, but the Lord looks on the heart” (ESV).

A relationship that involves mutual theologizing involves neither “a transcending set of truth claims” held perfectly by the dominant culture “acting as a referee to other opinions,” nor does it adopt a “simple pluralism that uncritically accepts all truth claims.” Rather, “critical pluralism,” that is, a thoughtful conversation between multiple perspectives equally seated around the theological table, is preferred as a method of co-edification.[vi]

Theologians from all over the world must have a seat at the table equal to those who hail from more dominant cultures. Their histories ought to be taken seriously. And their perspectives should be actively sought out as valuable such that they are invited to speak and not only to listen.

Thus situated, Mbiti’s biblically-resonant vision for “theological reciprocity and mutuality” is possible and even plausible for God’s people. Such a theological table conversation will raise previously neglected questions, challenge assumptions, and expose blind spots. Admittedly, this will cause discomfort for all involved. Yet this discomfort will be in the context of global theological table fellowship that will ultimately result in co-edification and the upbuilding of the universal Church.

Jessica A. Udall (jessie.udall@gmail.com), PhD, is an intercultural studies professor in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, an adjunct professor in the US, and a member of SIL Ethiopia. She has served in cross-cultural ministry in Ethiopia and among immigrants in the United States. She is the author of Loving the Stranger: Welcoming Immigrants in the Name of Jesus and the forthcoming Building Community Through Hospitality: Insights from Ethiopia for America’s Loneliness Epidemic.

[i] John S. Mbiti, “Theological Impotence and Universality of the Church,” in Lutheran World 21, no. 3 (1974): 6–18. Gerald H. Anderson and Thomas F. Stransky, eds., Third World Theologies (New York: Paulist Press, 1976), 17.

[ii] Samuel Deressa, “‘What Can the Rest Learn from the Rest?’ Nurturing the Culture of Global Conversation,” in Concordia Journal (Fall 2021): 37.

[iii] Keon-Sang An, An Ethiopian Reading of the Bible: Biblical Interpretation of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 2016), 2.

[iv] Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (New York: Oxford

University Press, 2011), 1–2.

[v] Deressa, “‘What Can the Rest Learn?’” 33.

[vi] Hui Leng Davina Soh, The Motif of Hospitality in Theological Education: A Critical Appraisal with Implications for Application in Theological Education, ICETE (Carlisle: Langham, 2016), 72.

EMQ, Volume 60, Issue 3. Copyright © 2024 by Missio Nexus. All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission from Missio Nexus. Email: EMQ@MissioNexus.org.

Responses