Cultural Bridges and Momina Traditional Religion: Seeking a Key Redemptive Analogy and Mission Many

by Les Henson

In his work with the Momina, Henson found four significant cultural bridges that facilitated the communication of the gospel and biblical truth to the Momina people.

In the early 1990s, a linguistic consultant and Bible translator who had been working in Indonesia shared how she and her language partner had unsuccessfully tried for many years to discover the one key redemptive analogy that would open up the tribe they were working among to the gospel. I expressed my concern at the danger of looking for one key analogy and shared the many bridges I had discovered within the traditional culture of the Momina. When I finished speaking she said, “I wish I had understood this years ago, because in looking for the really big redemptive analogy, my translation partner and I have missed many illustrations and seemingly insignificant cultural bridges that might have made a real difference to our language project and the communication of the gospel.” They had looked for the really big breakthrough and missed the many smaller but potentially significant breakthroughs along the way.

When I began working among the Momina people of the southern lowlands of West Papua, I was a keen observer of culture. As my language ability improved, I began to explore the peoples’ traditional religious beliefs and practices. This was a slow process for two reasons. First, it took a long time for the people to trust me sufficiently to share such knowledge. They needed to know that I was a worthy recipient and could be trusted to handle the knowledge carefully once it had been shared. Second, they were in the process of radically breaking with the past. Therefore, they were reluctant to talk about traditional beliefs and practices, believing them to be bad. Part of the reason for this was that Christianity arrived at a time when Momina society was in a state of disillusionment, disintegration and decline. Hence, they were open to anything new and condemnatory of that which belonged to the past. Yet, their old traditions were still very much part of who they were as a people.

I realized that if they did not deal openly with their old beliefs and practices, they could either remain implicitly under their control and power, or they would end up with a kind of schizophrenic worldview in which the Christian and traditional aspects of their culture were compartmentalized. Therefore, I was determined to come to an understanding of their traditional religion in order to help them work through the issues derived from their past, which, if left unresolved, would hinder their newfound faith. I believed that out of this study would emerge redemptive analogies or cultural bridges that would facilitate a fuller understanding of the Christian faith by the Momina believers.

In searching for redemptive analogies and cultural bridges, I was following Don Richardson and Eugene Nida. Richardson asserts that God’s key to unlocking people groups for the gospel is found in the redemptive analogies of their myths and practices, which act as stepping stones to facilitate the reception of the gospel. For the Sawi people of West Papua, among whom he worked, the peace child ceremony provided the key redemptive analogy for a society which elevated treachery and deceit as the highest virtue. He advocates that redemptive analogies are biblically approved approaches to cross-cultural mission (Richardson 1974). In a later work, he follows Wilhelm Schmidt’s now defunct diffusionist model in his effort to explain redemptive analogies in other cultures (Richardson 1981). Richardson’s idea of redemptive analogies has become very popular in evangelical mission circles since the mid-1970s.

Nida suggests the approach of cultural bridges which affirms that within any culture there are many bridges that facilitate the communication of the gospel. Some are little more than illustrations, while others are similar to Richardson’s redemptive analogies (Nida 1971).

More recently, Richardson has begun to use both terms with slightly different emphasis suggesting that

redemptive analogies may be either general to many cultures or special to one culture….General redemptive analogies communicate to a wider audience but are less potent cultural bridges (2000)

In the remainder of this article I will use the term “cultural bridges”; however, in doing so, I include all that Richardson intends when he refers to special redemptive analogies. There are four significant cultural bridges that facilitated the communication of the gospel and biblical truth to the Momina people.

1. The Name for God

When I began to live permanently among the Momina in 1979, my Dani coworkers were using the Indonesian loan word, Allah, for God. This was the term used by the Dani themselves and the Yali to the north. After about three years working with the Momina, I coined the expression, Yookoneema mee Ai (meaning, the creating Father). This was used until early 1987 when, after conducting extensive anthropological research, and after much discussion with church and community leaders, we began to use the name of the local high god, Botooma Rino Booto, a mysterious figure who seems almost unknowable. He is regarded as high, distant and as the most powerful of all the Momina spirit beings. His abode is above the clouds where the “people who shed their skin”1 live, and below the canopy that, like an upturned saucer, encloses the sky. The name Botooma Rino Booto literally means, “the strong sky canopy” or translated dynamically, “the All-Encompassing One.”

In the past, Botooma Rino Booto may have been considered the creator, but this is uncertain. He is not an ancestor. He lives by himself and does not have a wife. He was not born (meaning, he is of non-human origin) and no one has ever seen him. He sends earthquakes, thunder and lightning and causes the sky to be red like blood. This is evidence of his anger and of signs connected with the falling of the sky and the destruction of the earth at the end-times. At some future cataclysmic event, he will break through the canopy that encloses the sky and cause the sky to fall. There will be an earthquake that will cause the mountains and trees to fall down. The people’s bows and arrows will rise up of their own accord and shoot their owners. The “people who shed their skins” will be sent down to the earth to kill all the animals and perhaps take the shaman and dreamers back up to the sky. Certainly, all spirit beings that inhabit the earth will be destroyed. Then, the “people who shed their skins” will go up to the new and final sky (aikooro beea) and live with Botooma Rino Booto in what is thought to be a very good place. There they will continually renew their skins (ke keaeema) and so possess eternal life.

While there are elements in the Momina understanding of Botooma Rino Booto that are incompatible with the biblical record, these are minor issues compared with the overall understanding, which presents many areas of commonality. Therefore, because the excess baggage associated with this name was minimal, it was accepted as the Momina name for God. In the future, with the spread of the Indonesian language, there may possibly be a move toward the re-adaptation of the term Allah. However, if and when this occurs, the understanding of the nature and character of God will have been established so that the new term will carry with it this associated meaning.

In using Botooma Rino Booto as the name for God, it was necessary to clarify the Momina’s understanding of God by teaching about his nature and character. The notion of Botooma Rino Booto being far away and unknowable was counteracted with teaching about the imminence and omnipresence of God. Likewise, the Momina understanding of Botooma Rino Booto coming in judgment at the destruction of the world fitted in well with the teaching of scripture concerning the endtimes. However, it was necessary to carefully teach the concept of a loving God who is daily concerned with and cares for his people.

2. The God of the Ancestors

The Momina understanding of Botooma Rino Booto was passed down from one generation to another and validated as coming from the ancestors. Therefore, I presented God to them as “the God of their ancestors,” explaining that their ancestors had known God but they had become separated from God because of sin and disobedience. Consequently, the gospel was explained as the way back to relationship and fellowship with God. This idea of the God of the ancestors has its biblical parallel in the relationship of Yahweh to the people of Israel. God is referred to as “the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob” (Exod. 3:6). That is the God of the ancestors.

This presentation proved to be very meaningful to the Momina people as they have great respect for the ancestors and for the stories handed down by them. It also fitted in very well with the Momina story of the fall and the remnants of a flood story that exists in Momina mythology. The result was that they were excited by and responsive to this teaching.

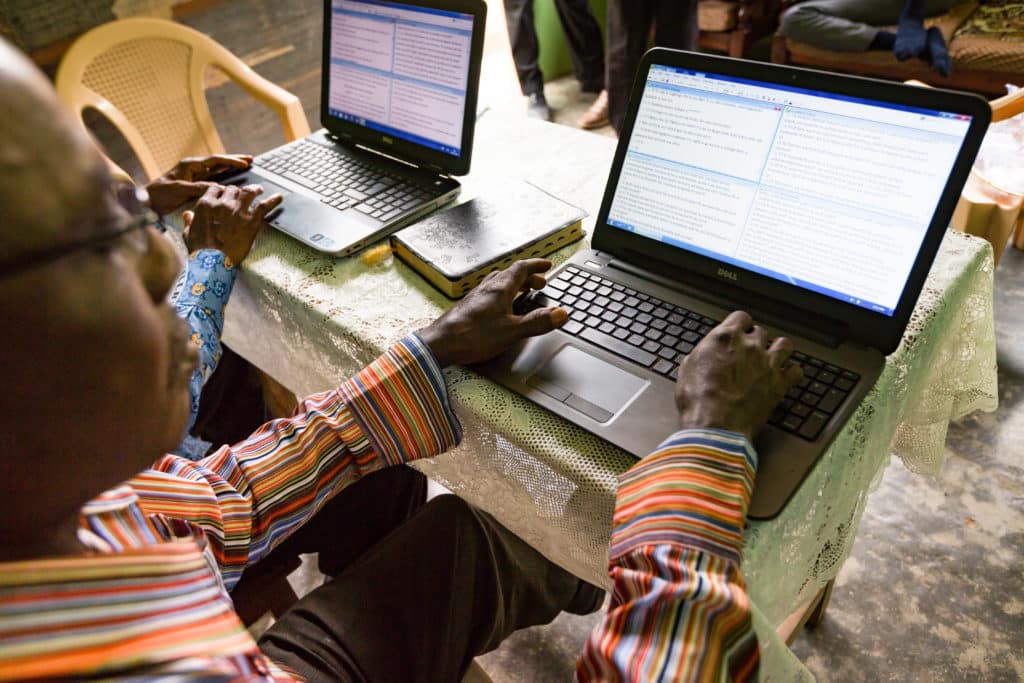

It is interesting that, when I was working with my translation helper, Konee Woin, on the translation of Genesis 1-11, he suddenly came to realize that there was significant correlation between these chapters and the Momina mythology and spirit cosmology. He concluded that the Momina stories of the fall and the flood, along with their understanding of Botooma Rino Booto and the sky “people who shed their skins” (ke keeaeema mee nya), were the same stories as those contained in Genesis 1-11. When he came to this realization, he excitedly exclaimed, “These are our stories! They’re the same! But our stories are out of shape and crooked because our ancestors moved away from God (referring to Babel) and did not remember them properly.”

3. The Name for Satan

Ron Ko Booto (the Strong Ridgepole), the name of the most powerful of the malevolent spirit beings, was used as the name for Satan among the Momina. The Momina were already identifying this spirit being from their cosmology with the biblical counterpart. Therefore, I felt it was wiser to confirm their choice and bring this into the open so that any confusion could be dealt with and avoided.

Unlike the clan founders, Ron Ko Booto is not a local deity; rather, he is recognized as exercising a greater and wider influence. A correlation is evident between Satan as presented in scripture and Ron Ko Booto as seen in the Momina spirit cosmology. He is the instigator of sickness (cp. Job 1) and will be destroyed by Botooma Rino Booto at the endtime (cp. Rev. 20:11). He is associated with the feast of snakes and lizards that provides the setting for the Momina story of the fall, and his name symbolizes death, which is a consequence of the fall story (cp. Gen. 3). In adopting Ron Ko Booto as the name for Satan, it was important to clearly explain the nature and activity of Satan as taught in scripture.

Interestingly, the choice of Ron Ko Booto as the name for Satan unwittingly created a translation problem. When my SIL colleague translated Luke 20:17 and Acts 4:11, in which Jesus is identified as the “capstone” or “cornerstone,” she used the Momina term ron ko (ridgepole). Technically speaking, this was the correct dynamic equivalent, being that which locks or holds the building together. However, in using this term these passages were identifying Jesus as Satan or (the symbol of) death. Thus, Acts 4:11 which reads, “He [Jesus] is ‘the stone you builders rejected, which has become the capstone’” was conveying a very different meaning from that intended. It was saying, “He [Jesus] is ‘the stone you builders rejected, which has become Satan or Death.’” Using the expression for the forked-upright pole located at each end of the longhouse temporarily circumvented this problem until a more suitable expression which brought it more in line with the original was found.

4. The Fall and the Loss of Eternal Life

The Momina story of the fall and the loss of eternal life contains many similarities to Genesis 2 and 3 and was used to teach a Christian perspective on sin, its consequences and the loss of eternal life. See Momina story in the box below.

By comparing this story with Genesis 2 and 3, I was able to point out the following similarities in the accounts:

1. Both stories speak of a prohibition. One prohibits sexual intercourse between the husband and the wife, while the other prohibits the eating of the fruit of “the tree of the knowledge of good and evil” (Gen. 2:16-17).

2. Trees play a central role in each story. For the Momina, the central focus is upon “the earth’s tree,” while in Genesis both “the tree of life” and “the tree of the knowledge of good and evil” are pivotal to the development of the narrative.

3. The two accounts portray humanity as being in a state of purity prior to the breaking of the prohibition. In both stories, humanity and the created order are described as “very good” on the one hand, and “only good [without sin]” on the other.

4. Both accounts depict humanity as experiencing unbroken communication with God/heaven. In Genesis, we see the Lord God “walking in the garden in the cool of the day” (Gen. 3:8), symbolizing God’s intimate relationship and presence with Adam and Eve. In the Momina myth the earth’s tree represents the trail or ladder to heaven which was accessible to humanity prior to the fall.

5. Both stories emphasize the influential role of the woman in violating the prohibition. In the one account Eve is tempted by the serpent, succumbs and leads her husband into sin (Gen. 3:1-6). While in the other it is the wife of the “man of the earth” who initiates and harasses her husband into breaking the prohibition on sexual intercourse.

6. Hiding and avoidance are the immediate results of the breaking of the prohibition. In the Momina myth the wife is not present when her brother, the “man who shed his skin,” returns. The implication is that she is ashamed and is seeking to avoid him. In the Genesis account both Adam and Eve become aware they are naked and are ashamed as a result of their sin; therefore, they try to hide from God (Gen. 3:7-8).

7. In both cases, there are long-term consequences resulting from breaking the prohibition. The Momina account reveals that death, sickness, loss of eternal life and a break in communication with the heaven and the people “who shed their skin” are the consequences of such action. In Genesis, the consequences are spiritual and physical death and alienation from God, people and the land.

8. In both stories, access to the tree that brings life is denied. In Genesis, the “cherubim and a flaming sword…guard the way to the tree of life” (Gen. 3:24). In the Momina version the earth’s tree is defaced, indicating that the way to heaven is barred and eternal life is no longer accessible.

In comparing the Momina myth with the Genesis story of the fall, I was able to teach about foundational issues in the Christian faith in a way that spoke to perceived needs of the Momina people. Sin was portrayed in terms of a break in relationship that resulted in disharmony with God, the spirit world, one another and the created environment. An emphasis on the loss of eternal life and the way of regaining it through relationship with Jesus Christ met the Momina at the point of their greatest longing—the desire for eternal life. This was facilitated by the use of the indigenous expression ke keeaeema (“the shedding of the skin”) as the term for eternal life.2 This was particularly important for the older generation who were thoroughly in tune with their mythology.

CONCLUSION

In seeking to bring the gospel to the peoples of the world we need to be open to the rich array of redemptive analogies and cultural bridges that are waiting to be discovered. But let us be careful lest we seek one big breakthrough and miss the many small bridges that are waiting to be discovered that provide potentially significant breakthroughs along the way.

>> SEE ACCOMPANYING ARTICLE: The Momina Story of the Fall and the Loss of Eternal Life

Endnotes

1. The “people who shed their skins” (ke keeaeema mee nya) are thought by the Momina to be distant ancestors who have gone to live in the sky. Whenever they show outward signs of aging, they take off their skin to renew their youth. Through continual “shedding” they live forever, without sickness or hardship. The shedding of skin, as a symbol of eternal life, is not uncommon in the traditional societies of West Papua.

2. Although the idea of growing old and shedding one’s skin (thus becoming young again) is alien to the biblical concept, it need not be rejected. Melanesians always convey important conceptual truth in concrete terms.

References

Nida, Eugene A. 1971. “New Religion for Old: A Study of Culture Change in Religion.” In Church and Culture Change in Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: N.C. Kerkboekhandel.

Richardson, Don. 1974. Peace Child. Glendale, Calif.: Regal Books.

______. 1981. Eternity in Their Hearts. Venture, Calif.: Regal Books.

______. 2000. “Redemptive Analogies.” In Evangelical Dictionary of World Mission. ed. A. Scott Moreau. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker.

—–

Les Henson spent nineteen years church planting in West Papua with World Team. He is currently senior lecturer in intercultural and mission studies at Tabor College in Melbourne, Australia.

Copyright © 2008 Evangelism and Missions Information Service (EMIS). All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission from EMIS.