Funding Kingdom Work By Building Financial Capacity in National Organizations

by Mary Mallon Lederleitner

Wycliffe International’s “Matching Funds Experiment” produced significant results for the Church to consider when considering models of local and global giving for missionary support.

As the locus of missionary-sending countries is transitioning to the Majority World, there is a pressing need to find avenues to fund those called to work in ministry in ways that will raise needed resources while still engaging local support and ownership. Wycliffe International’s “Matching Funds Experiment” has produced some intriguing results for the global Church to consider. The experiment had two components. The first encompassed the sending of three consultants (including myself) from various countries to do partnership development training for colleagues in three other countries. Our hope was to equip people to more effectively raise funds in their own contexts. How this played out in each country was slightly different. However, the results at the Translators Association of the Philippines (TAP) were considerable. The second aspect of the experiment entailed a fund-raising initiative by Wycliffe UK. They presented the needs of the workers through an online campaign, as well as to major donors, in an attempt to raise funds that would match or supplement local funds raised in culturally appropriate ways. As the team (including myself) examined the results, a number of issues appeared to be quite significant.

1. Perspective Is Critical

Although partnership development (PD) training was provided to TAP members in the past, nothing ever changed. Some members had served for twenty years and yet had never seen their support increase. Instead of focusing on newsletters or teaching people how to share two or five-minute modules with their churches, a different approach was used. The consultant, Myles Wilson1, focused first on heart issues. He spent a great deal of time sharing how Jesus funded his ministry through gifts from friends like Joanna and Mary Magdalene (Luke 8:1-3). This was the first time someone addressed the biggest obstacle TAP members faced in raising support: they lived in a shame-based culture and felt like beggars if they asked for financial support from friends and family. In their context, to become a beggar was one of the greatest forms of shame any person or family could endure.

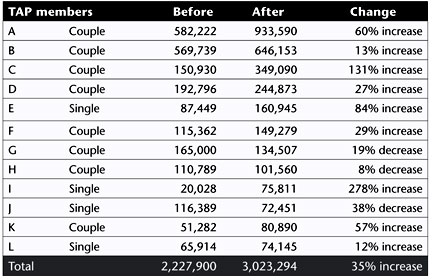

For the first time many TAP members experienced a perspective transformation that served as a catalyst for different results and personal growth. Instead of feeling embarrassed and ashamed to ask people to join their ministry teams, they now saw PD as modeling the behavior of their Lord and Savior, who was neither a beggar nor a failure. Although additional TAP members were involved in this experiment, the chart below includes those who were involved in raising support for their ministries the year before the experiment and the year following the start of the experiment. This data (in pesos) has been included to provide quantitative analysis to supplement and support anecdotal information.

As the one who coordinated the experiment, I visited Manila to speak to each of the participants after the quantitative data was collected. I wanted to understand why some people experienced progress and others did not. It was through these discussions that the issue of perspective became so apparent. Single I said, “I always believed that Ilocanos do not ask for money. Myles shattered my negative perspective!” Couple D said, “Our whole perspective changed! For the first time we realized we really could ask our friends.” Others are not included in the chart on the following page because they had just started raising funds to go abroad, and there was no comparative data available. However, time and time again, when an increase in support was present, there were also comments on how negative perspectives had been changed. Even when people had little time to raise funds due to heavy work schedules, if their perspective became more positive, their income increased. This was the case with Single L, whose language project was especially intense during this period. She said, “How can you face people if you think you are a beggar? For me, PD is a service. It is lifting up God and others. The mindset of Filipinos needs to change.”

As I talked with those whose support had decreased, a negative perspective about PD seemed to be at the core. Couple G said, “To ask people to support us in our culture is not permitted. We are thinking of planting some rubber trees for income.” The amazing thing was that the ministry of this couple was utterly exceptional. A substantial revival was taking place in their language project. Many were coming to Christ; supernatural healings were taking place. They were back in Manila frequently surrounded by all kinds of people who were not of the same ethnic heritage. Many believers would have felt blessed and privileged to partner with what God was doing in and through them.

It is unrealistic to approach people from a shame-based culture and ask them to raise their own support without spending extensive time in the beginning and throughout the process addressing the heart of their concerns. In many countries and within many families, raising personal support is seen as “begging.” One of the things that made this effort more effective than PD training in the past was examining such cultural beliefs in light of scriptural realities. The word of God is powerful (Heb. 4:12). Only as people gain a new perspective from God’s word can they muster the courage to develop the new skills required to find greater resources for their ministries and for the kingdom.

2. Spiritual Breakthrough

Alongside and in conjunction with perspective transformation, a significant spiritual breakthrough happened early in the PD training process. This related to the issue of giving and sharing resources. Early in the first training session, Myles assigned homework on this topic. Participants were to examine a number of scripture passages about giving and allow God to examine their hearts in light of this truth. The next morning, Myles asked if anyone would like to share what God taught them. Participants began crying and confessing sinful attitudes and behaviors. Many had resentment in their hearts toward people who were always coming to them wanting money and food. Others, because of low support levels, had not been giving tithes or offerings for many years. After an hour and a half Myles had to stop the sharing because he was afraid he would never get to the other things he needed to cover. However, it was obvious that God was touching and softening hearts. A year later, many referenced this moment as a significant point that changed how they viewed asking, giving, and receiving.

3. Gentle Accountability Structure

When I was asked to oversee this experiment, I had one serious concern: growing in PD skills seemed to mirror some of the research in Emotional Intelligence Training. What Wycliffe International was trying to facilitate was changed behavior, and yet typical PD training was modeled after courses focused solely on cognitive growth. I was concerned that if each organization receiving training did not implement some type of contextually appropriate accountability process, any gains in inspiration and motivation would be short-lived. As such, I asked each of the three organizations to consider contextualizing an accountability process which would serve them best. All said they would consider it; however, TAP was the only entity to develop one and put it into practice. There was no significant increase in local funds raised in the other two entities. However, when the support of all the TAP members was calculated, including new members who initially were quite uncomfortable with raising support, donations for the organization increased more than fifty percent.

One especially intriguing aspect is the similarity of TAP to one of the other organizations included in the experiment. Both indigenous organizations had members who, for many years, had served with low support. Both contexts had a strong Catholic presence and a growing evangelical Church that was starting to send more missionaries. Both organizations had many members who served within their own national borders, yet were not seen by the evangelical churches as being “true” missionaries. Both contexts wrestled with a shame-based culture. And, most striking, both of the PD consultants were trained and mentored by the same person, so their styles and methods were incredibly similar. I did not realize this last point until much later in the process; however, I always thought it was amazing that these two men seemed to approach ministry in such a similar way despite being from different countries. So what caused the difference? Why did TAP see such great results, but this other indigenous organization with very similar demographics did not? Both groups truly enjoyed, appreciated, and felt motivated after the end of the initial training session. However, TAP implemented a contextually appropriate and gentle accountability structure and the other entity did not. For this reason, I am even more deeply convinced that this is a critical piece for the training to be effective.

4. Staged Training Process

Another distinction in the experiment was the way training was conducted at TAP. In the other two entities, the PD consultant visited one time. The TAP training was handled quite differently. It was a staged training process, and on the first visit Myles met with the group for just a few days. Then, each person was assigned homework, and he or she met one-on-one with Myles on more than one occasion. Approximately seven months later Myles visited again to find out how things were going. Again, he met with everyone for a couple of days as a group and then spent a few days meeting with people one-on-one. On the third visit there was a group meeting for just one day. It served as a refresher course, and then Myles met once with each participant. In each personal consultation, he included one or two TAP members who would later act as coaches and trainers. Together Myles and the TAP leaders considered the progress that was made and what was needed to make the change sustainable. One final visit is scheduled to train the TAP trainers who will now have the confidence and ability to lead others in their organization. Myles will arrive early and work with the trainers. The trainers will then do all the training sessions and Myles will simply sit in the back and watch. He will later meet with the trainers to coach them further and answer any of their questions. Myles requested this staged training process before agreeing to do this work for Wycliffe International in the Philippines. He requested it because he felt it was not just PD training but organizational change that was being sought. In his words, “That simply does not occur in one visit.”

Amidst this formal, staged-training process, TAP members provided ongoing coaching for one another as well. They instituted the gentle accountability process as noted earlier, and this included a report the participants designed themselves to help each other stay on track. If the reports showed someone was struggling, others in the organization would call or meet with them to talk through obstacles or difficulties. By having a staged training process combined with ongoing coaching and encouragement, it enabled people to develop confidence and the ability to exercise new skills.

5. Management Expectations

In addition to the other changes which took place at TAP during this process, managers within the organization made support raising a priority. They began building this emphasis into the culture of the organization by discussing it at meetings, having people share testimonies, and allowing people time to meet with potential supporters. This was key, as then it was not just “a form to complete” or “required training to attend.” Instead, it became natural for TAP members to discuss PD on breaks, during meals, and in other informal interactions as they worked together.

6. Matching Funds as a Motivator

I was not sure how matching funds from abroad would factor into this process. Through the interviews, however, it became apparent that they served as a serious motivator which gave people courage to “try again” even though, in the past, PD efforts were never productive. It also seemed to convey to TAP members that their colleagues throughout the worldwide family of organizations finally understood that it might not be as easy for them to raise funds locally as it would be for those coming from wealthier countries. One person described it as an “emotional buffer” in that she was not approaching people empty-handed or alone. Matching funds represented to her that somebody, or a group of people, was behind her and valued the work she was doing. As such, it made it easier to ask others to give as well.

Insight gained from the Wycliffe UK fundraising initiative was intriguing. Geoff Knott, CEO of Wycliffe UK at the time, developed an extremely creative initiative to see if giving could be facilitated electronically through a “Hands-in-Hands” website. Although the site received many visits and seemed beneficial for promoting awareness about Bible translation and literacy, the outcome for funding was minimal. However, the place where this initiative was most effective was with major donors. Wealthier people seemed to sense the significance of this type of fund and the impact it could have for motivating and empowering others for local support raising.

The guidance team also made a critical decision that, in hindsight, was very important. After discussing various options, the team decided that how the matching funds were to be administered was to be decided by each indigenous organization. The team believed the leadership in each organization was best suited to make that call as only they would understand the impact on members and the ripple effects of such a decision. At first, some indigenous leaders balked at this—they wanted the team to make the decision. However, TAP leaders later said they deeply appreciated that they were the ones who had to wrestle with those issues. In conjunction with their board members, they arrived at a more complicated allocation than the guidance team would have ever recommended. However, in the end their process for allocation of matching funds reflected deep grace for all their members as well as deep reward for those who were investing more energy into PD efforts. It modeled tremendous wisdom and forethought.

As a whole, the matching funds have been a blessing. One TAP member said, “Before I just lived one day at a time because I could not see how things would ever improve. I tried to be faithful with what God was giving me. Now, because of the matching funds experiment, I have dreams for the future—for what God can do in and through me for my people!” I was reminded again of how much TAP members continue to give to others in spite of their own personal needs. Many have one or two advanced degrees and several have left good jobs (which in the Philippines are not always easy to find) to work in ministry. It was inspiring to see what they were doing with the resources entrusted to them.

An unexpected negative side-effect came to the fore as well. When the matching fund experiment was set up, Wycliffe International limited the number of participants from the three entities involved. In hindsight, this should not have been done. The program should have been made available to everyone who wanted to participate in each of these organizations or it should have been limited to just one or two organizations. The guidance team made this restriction because they feared that if the pool of participants became too broad, the benefit to each participant would have been so minimal that it would have made no material difference in anyone’s life or ministry. The hope was that those who had seen good results would be able to then help others within their organization. However, I realized that in TAP the distinction was causing tension between those involved in the matching funds program and TAP members not involved. Upon realizing the implications of this decision, which was made abroad, I apologized and the scope of the experiment was changed to include anyone from TAP that their leadership and board felt should be included in the matching funds program.

7. A Strong Felt Need for More Support

The last reason this experiment was so helpful was that TAP members had a strong felt need to raise more support. In reality, many of them had been suffering on low support for years. This lack was impacting them in tangible ways. Because of this need, they really did not have anything to lose by trying to raise more support locally. The dynamics of how this type of transition will occur if indigenous colleagues are currently wholly funded by foreign salaries is not yet clear. Those involved must have something to gain for the efforts they are extending or it seems unlikely that any lasting organizational change will occur.

Additional Thoughts

As this experiment is coming to an end, I am aware that there are many other avenues to consider for raising local support. TAP members are using “advocates” to act as go-betweens, especially to new donors whom they do not know personally. Many feel quite comfortable with this since their cultural communication style is indirect by nature. Another organization is starting up in the region with high hopes of engaging donors of great wealth. This has wonderful possibilities for bringing greater resources into the Kingdom of God to fund workers from this part of the world. However, through the informal communication channels, some individuals have explained that all people will be “fully funded” by these wealthy donors. They have said the wealthy individuals think it is embarrassing that missionaries have to “beg” and this “begging” gives missions and the Church a bad name.

I am concerned that if these sentiments form the foundation of new organizations of wealthy donors, they run the risk of forming a condescending post-colonialism, whereby wealthy Asians will simply repeat the mistakes Western missionaries made before them. Raising support for ministry and asking people to consider giving to kingdom work and investing in what God is doing around the world is a privilege. All those who participate will be blessed. That blessing was never something God intended to reserve for the wealthy alone.

A beautiful lesson from Wycliffe’s Matching Fund Experiment is that it teaches that there are ways to blend together the gifts of the wealthy with the gifts of the middle class and the gifts of the poor. Some of the TAP members explained that when they asked extremely poor people to contribute to their ministries, the poor were inspired that their gift would be “matched” and would actually do more in the kingdom. It caused them to feel as though what they had to give was not insignificant, but rather, it had great worth. What an incredibly beautiful thing! Blessing for the poor who give, blessing for average wage earners, and blessing for the wealthy. Who then feels ownership for the ministry? Whose hearts and whose prayers are with these missionaries? Jesus said, “For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also” (Matt. 6:21). Only as all participate will all be blessed and will all own the work of the kingdom. Only then will there be true sustainability. Only then will Christ’s purposes for the world be wholly realized.

Endnote

1. Myles Wilson was born and raised in Ireland, where he currently resides. He authored Funding the Family Business, a workbook that can be contextualized to fit diverse cultural settings (see https://www.fundingthefamilybusiness.org).

….

Mary Mallon Lederleitner is a researcher, author, trainer, and consultant for Wycliffe International. Her focus is best practices related to cross-cultural ministry partnerships. She is pursuing a doctorate at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. She also serves on the steering committee of COSIM (The Coalition on the Support of Indigenous Ministries).

Copyright © 2009 Evangelism and Missions Information Service (EMIS). All rights reserved. Not to be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission from EMIS.