How useable are Adult Learning Principles across cultures?

By Susan C, as a research assignment for an academic subject.

Written July 2016. Reformatted and updated Oct 2019.

Abstract

This article attempts to answer the question, ‘Are the values and assumptions of various cultures in conflict with adult learning principles, or are these principles culturally transferable?’ We use Jane Vella’s six core principles of Dialogue Education and assess their practicality in regard to cross-cultural training by considering them alongside Hofstede’s Dimensions of National Culture. The short answer found is, ‘Yes, the principles themselves are culturally transferable.’

A longer answer includes others nuances. These include:

- the danger and common mistake of transferring behaviors and strategies rather than the principles;

- that each culture will find at least one of the principles stretching and uncomfortable (but that this is healthy);

- that two of Hofstede’s dimensions[1] in particular can cause tension and that one is due extra consideration when planning because of its pervasiveness;

- affirmation of Vella’s description of Dialogue Education as a robust, integrated, and growing methodology;

- that further research and reflection is helpful in regards to a number of topics.

The conclusion is that if the principles of adult education are faithfully and appropriately applied in a new cultural context, it can be a very effective model for learning across cultures.

Questions often posed regarding adult education and cultural contexts are: “Is the concept of adult education an educational philosophy based on western cultural values?”, “Are the principles really applicable across cultures?”, “Are the values and assumptions of various cultures in conflict with the principles?”, and “Are there cultures where it just doesn’t work?” As an attempt to bring a researched answer, this article works through Hofstede’s six dimensions of culture, noting how Jane Vella’s six core principles of Dialogue Education relate to these, and assessing the cultural transferability of adult education as an educational paradigm.

Dialogue Education

In the 1980’s, drawing on the learning theories of adult educators including Freire, Bloom and especially Knowles, and reflecting and adapting from her own experience, Jane Vella formed an educational framework and termed it Dialogue Education.[2] Originally, Vella formed twelve axioms of Dialogue Education. These have recently been consolidated into six core principles that make up the model. They are: respect, safety, engagement, inclusion, relevance, immediacy.[3]

- Safety. Learning experiences require honest explorationand room for people to raise questions, talk about hard lessons learned, and admit what they don’t know.

- Respect. Ensuring that participants can exercise control and choice in their learning experience is just one way to create mutual respect and a path for learning.

- Inclusion. While participation is relatively easy to pull off, inclusion requires something more, the ability not just to speak, but to be understood.

- Relevance. Adults will find it worth the struggle to learn from others when learning focuses on issues and skills that matter in their own work or life.

- Immediacy. Building immediate application into all learning opportunities helps learning lasts when adults immediately apply what they are learning.

- Engagement. Adults learn best when they are actively involved in the process of learning alone and with others. Learning is in the doing and deciding.

In her books, Vella gives case-studies of the principles in action from Ethiopia, Tanzania, Indonesia, a migrant labor camp in the US, the Maldives, Nepal, Zambia, El Salvador, Zimbabwe, North Carolina, the US, and Bangladesh.[4] Such a variety of contexts provide anecdotal testimony to the wide application of the original twelve axioms. This article will not use examples, work through a framework of cultural values, assessing the applicability of each of the core values.

Considering the Principles in the light of the Dimensions

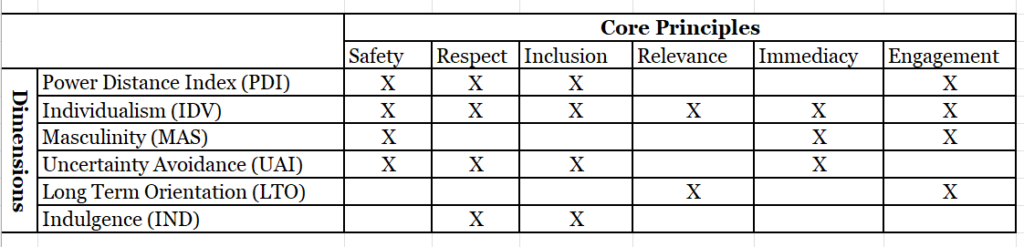

We now turn to consider the principles of Dialogue Education against Hofstede’s cultural framework.[5] The table below outlines which core principles are discussed in relation to Hofstede’s dimensions.

The first dimension is Power Distance. This measures how a society deals with the inequality present in the society.[6] The higher the Power Distance Index (PDI), the more stratified the society is, with the resulting influence and power differential between individuals and groups. With this dimension in mind the four principles of safety, respect, inclusion, and engagement need to be handled sensitively. The aim is give appropriate control and choice to empower those in the group without societal influence, while showing due respect to those with authority and influence. In a high PDI society, allowing honest exploration in a safe place of learning and genuinely including all voices requires significant cultural sensitivity.

An example from Brookfield’s research found that in contexts of high PDI, uncontrolled discussion in a room could actually increase the unbalance of power and be a tool of oppression. He therefore adapted his method. First, he focused on learning how the learners experienced the discussion circles, then he verbalised limitations of the circle. He explained that it didn’t remove the power, and he adjusted the practice and clarified the freedom of learners to choose not to speak.[7] Law’s ‘sharing by invitation’ version of a discussion circle was created to encourage all to have the choice to add to discussion, or not, in a high PDI environment.[8] In this way safety of the learning space is guarded, respect is shown to all learners, inclusion is offered to all, and there opportunity for immediate engagement. Done carefully, this can help learning rather than stifle it. Another strategy is the use of “group media” to healthily distribute power within a group with a high PDI.[9] These learning activities are unusual in high PDI contexts, and therefore require the endorsement of those of high status in the group. They can also be uncomfortable, but the aim is not most comfort, but most learning. Handling the group power dynamics sensitively can lead to a higher status person learning from someone of lower status – something that would not normally happen in a high PDI situation.

Within high PDI contexts there is often little personal freedom of behaviour and dress. The dress and initial behaviour of the teacher is extremely important. If the teacher working within the Dialogue Education model does not dress as a teacher should, or begins the class with a highly unusual activity, the learning process will almost certainly be undermined. At this point there is a potential tension between the high PDI values and the importance of learning from one another in Dialogue Education. The expectations placed on a teacher are not only her dress and terms of address, but also include appropriate ways to act. Operating by the principles of Dialogue Education will almost certainly not fulfil these expectations regarding behavior. To counteract this, it is important for the teacher to clearly articulate expectations and the rationale of any different behaviors.

An equally important concept to understand and respond to is that of the “hidden curriculum”. This is the unintended curriculum – things “which are not part of the formal school curriculum, but are instead acquired as part of his or her experience within the social contexts.”[10] They include speech patterns, codes of behaviour and social attitudes. In this situation, hidden curriculum can come from the cultural environment, the learners, and the teacher. Discernment is key for the teacher to recognize any hidden curriculum and to be able to acknowledge it, then either sensitively negate it or include it in the learning experience. When done well, this enables the teacher to keep to the adult education principles with as little discomfit for the learners as possible. If not negotiated wisely, the discomfit of learning becomes too great, and the learning experience is rejected as unsuitable. Knowles, Holton and Swanson refer to the successful negotiation of an unhelpful expectation as “unfreezing” a behaviour.[11]

Individualism (IDV) is the second dimension in Hofstede’s model. It measures whether interdependence or independence is fostered in the society. If IDV is high, individuals expect to plan, achieve and be rewarded as individuals. If it is low, cooperation and collaboration within groups is the expected social behaviour. Adult education is often assumed to be highly individualistic in nature, yet all of the core principles can be applied to a group as a whole as well as to individuals. Law provides an example of engagement in a low IDV context – a way of eliciting information in a group-oriented context. First, each person writes answers to a question on a separate piece of paper, and then all papers are handed to one person to read out and attach to a large sheet of paper, which is displayed on the wall.[12] In this way feedback and discussion are regarding the responses as a whole, rather than individuals’ answers. Understanding a group’s IDV value is key to establishing safety in the environment and in the process. Because the IDV dimension impacts all of the principles, it is absolutely vital to keep it in mind in situations of teaching across cultures. Because the IDV is so pervasive, as part of the preparation and planning, any teacher from an individualistic background should have all learning activities checked for IDV bias and assumptions.

Hofstede’s third dimension is Masculinity (MAS), the appeal of either assertive or modest behaviour. In a high MAS society, good management is seen to be decisive and even aggressive. On the other hand, consensus and intuitive decision-making are appreciated in management in low MAS contexts. MAS therefore majorly affects how safety is achieved, what are considered appropriate forms of engagement and immediacy. A teacher attuned to the MAS value will adjust the tone of his communication, and the activities and requested behaviors of the students as learners are invited to engage in the learning process. A low MAS group or context will appreciate more time given to reach consensus within the group. In such situations, the axiom ‘less is more’ is vital. It is important for the teacher to limit the number of activities to allow for learning in a low MAS manner.

The next of Hofstede’s dimensions is Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI). It measures how dangerous something that is unknown is perceived to be. A society with high UAI will have crafted behaviours, beliefs and institutions to minimise uncertainty. In a learning environment, this leads to an expectation for a structured situation, with information given clearly and answers that are obviously correct or incorrect. Learning activities based on adult learning principles can be crafted for both a high UAI or low UAI context. In a high UAI situation, giving information up-front is part of creating safety and showing respect. There is potential for tension with inclusion, and immediacy. If the teacher expected to know all the answers and give the needed information, frustration can come from the seeming ‘wasted time’ taken to allow each student to be heard and understood, and also for activities giving opportunity for immediate application. An important skill is therefore balancing the need for inclusion and immediacy with the respect for learners to have control and choice over the learning activities.

Since high UAI societies have a tendency to avoid new environments and technologies, the whole Dialogue Education process can seem threatening. In the face of such potential tension, wise communication is important. Such communication would lower anxiety by highlighting that this educational paradigm respects their control and choice as learners. When faced with contexts where a new method is not welcomed, Vella advises to carefully clarify the process and the rationale of adult education, and then leave the decision to the learners.[13] Such clarifying is with the aim of lowering any apprehension from an uncomfortable level to one of optimal discomfit – a level at which “unfreezing” can happen.[14] It may be that this outworking of respect and safety would lead to the learning space having the ‘look and feel’ of a more traditional teaching situation. This is a prime example of the wise application of the principles looking extremely different according to the context of learning and the cultural makeup of the learners.

Long Term Orientation (LTO), the second last dimension, describes the time-orientation of virtues of the society. For example, it affects the types of gifts commonly bought for children. Parents from a high LTO society tend invest in the educational and financial future of their children, while those from a low LTO society invest in the happiness today and feeling of being loved now. A high LTO can lead to a brusque pragmatism, undergirded by seemingly invisible concern and care. Practical problem solving is valued, and adaptation is accepted a necessary. A low LTO can lead to little future planning and slow economic growth, in the middle of obvious immediate care and concern.

So, how do the Dialogue Education principles relate in situations of varying LTO? A high LTO context can lead to tension in the areas of engagement and relevance. This means crafting learning activities to reduce unhelpful frivolity and to allow engagement in ways that the learners are comfortable with. It also entails presenting relevance of learning in a long-term, real-life perspective. In a low LTO context the teacher’s role is often to keep reinforcing the relevance of the main goals and objectives to the learners, so the learning experience is more than just an enjoyable experience. All six principles can be tailored to suit either the pragmatism (high LTO) or enjoyment (low LTO) focus of the group.

Hofstede’s sixth dimension is Indulgence (IND), measuring the extent to which people try to control their desires and impulses. Another way of describing it is the degree of freedom given to people to fulfil their human desires. A high IND context revels in life being more fun, and enjoying life. A low IND society is more circumspect with social customs regulating freedom.

Respect and inclusion are key principles for the IND dimension. If a teacher truly respects the learners, and appropriately ensures their inclusion in the learning process, the activities carried out can be appropriate to either low or high IND groups. This is another example where the learning situation could, and should, look very different. A wide range of activities are possible, all in line with the six principles. In a high IND situation, use of humour, spontaneous activities such as going out with the learners to last-minute social events will aid in learning. Alternatively, being sedate and thoughtful of the task at hand are helpful behaviours in a low IND situation.

Conclusion

Dialogue Education is one example of a system designed in the adult learning paradigm. Vella describes it as a “firm, integrated, and growing system”.[15] It is firm in that it clearly based on six core principles, and follows the seven questions of planning. It is integrated in the way that each of the core principles relates to, and affects the others. Through looking at each of Hofstede’s dimensions of culture, the growing aspect of this system is clear. Vella presents it as an ongoing research agenda where only the individual can know exactly what it will look like in their context.[16] It is flexible enough to re-shape to fit various cultural contexts, and both high and low of each of Hofstede’s dimensions. “The simplicity of the principles … they can be applied productively in educational enterprises anywhere.”[17] Dialogue Education is a growing system, as the potential application of model is always more than what has been seen so far.

As we have worked through Hofstede’s six dimensions, it seems that while all contexts can find aspects of adult learning stretching, societies with high PDI and high UAI have the greatest potential for tension with Dialogue Education principles. It was also noted that because of its pervasiveness, the IDV dimension deserves special attentional when planning. Yet we have seen that even in these highlighted areas it is possible to work within the principles with discernment and care.

It is important to note that just because these principles can be applied productively, doesn’t mean they are, or will be. What is often seen as the unhelpful norm of an adulting learning situation, is a noisy room without order, with lots of post-its, and ‘silly games’. After working through each of Hofstede’s dimensions of culture, it is obvious that a classroom, run faithfully by Dialogue Education principles, could and even should look traditional (i.e. quite formal and quiet with an obvious teacher in charge) in some settings.[18] The caricature also highlights that is it very easy to do a good thing badly. It is very easy to teach poorly in a new or multi-cultural environment by simply transferring the expected behaviors and learning activities from one context to another. It is difficult to teach well within the adult learning paradigm, requiring extra preparation for the content and the process, intense observation and interaction during the event, and follow up afterwards.

Five years after publishing Culture’s Consequences, Hofstede was applying his insights into educational situations. He had observed and personally experienced difficulties in cross-cultural learning situations, and now had language to describe what was happening, by referring the differences to the (then) four dimensions, thus providing an explanation for the differences.[19] He concluded that in situations of cross-cultural learning, the teacher bears the responsibility of adaptation. Wise cross-cultural educators will realise that they carry the responsibility of adapting to their context, and apply Vella’s principles with much prayer and caution in these situations.

There are a wide variety of contexts where adult learning has been used successfully, and also a wide variety where use has not been successful, or has not been accepted by the learners. Dialogue Education is not a magic method that ensures learning in any cultural context. Taking it and using it, unchanged, from another cultural context, is the same as simply exporting any form of teaching – as just as prone to failure in regards to real learning. Using it well requires listening, learning, adapting, humility, and perseverance.

In any cross-cultural or multi-cultural teaching situation, the crucial question is “How then do we bridge these cultural differences and create classrooms in which effective teaching and learning take place?”[20] Using Hofstede’s dimensions as a framework, we have seen that if the principles of Dialogue Education are faithfully and appropriately applied in a new cultural context, it can be a very effective model for learning across cultures.

Bibliography

Bowen, Earle, and Dorothy Bowen. “Contextualizing Teaching Methods in Africa.” Evangelical Missions Quarterly 25, no. 3 (1989): 270-75.

Brookfield, Stephen. “Understanding and Facilitating Moral Learning in Adults.” Journal of Moral Education Vol. 27, no. 3 (Sept 1998 1998): 283-301.

Hofstede, Geert. “Cultural Differences in Teaching and Learning.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 10, no. 3 (1986): 301-20.

Knowles, Malcolm S., Elwood F. Holton, and Richard A. Swanson. The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development. Eighth edition. ed. London ; New York: Routledge, 2015.

Law, Eric H. F. The Wolf Shall Dwell with the Lamb: A Spirituality for Leadership in a Multicultural Community. St. Louis: Chalice Press, 1993.

Lingenfelter, Judith E., and Sherwood G. Lingenfelter. Teaching Cross-Culturally: An Incarnational Model for Learning and Teaching. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2003.

Uccellani, Val, and Anouk Janssens-Bevernage. “6 Core Principles, Virtually!”: Global Learning Partners, 2013.

Vella, Jane. “Global Learning Partners.” http://www.globallearningpartners.com/index.php.

Vella, Jane Kathryn. Learning to Listen, Learning to Teach: The Power of Dialogue in Educating Adults. Rev. ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2002.

Bovill, C., L. Jordan, and N. Watters. “Transnational Approaches to Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: Challenges and Possible Guiding Principles.” Teaching in Higher Education 20, no. 1 (01// 2015): 12-23.

Bowen, Earle, and Dorothy Bowen. “Contextualizing Teaching Methods in Africa.” Evangelical Missions Quarterly 25, no. 3 (1989): 270-75.

Brookfield, Stephen. “Understanding and Facilitating Moral Learning in Adults.” Journal of Moral Education Vol. 27, no. 3 (Sept 1998 1998): 283-301.

Hibbert, Evelyn. “Designing Training for Adults.” In Integral Ministry Training: Design and Evaluation, edited by Robert Brynjolfson and Jonathan Lewis, 51-64. Pasadena: William Carey Library, 2006.

Hibbert, Evelyn, and Richard Hibbert. “Training Missionaries: Principles and Possibilities.” in Press.

Hofstede, Geert. “Cultural Differences in Teaching and Learning.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 10, no. 3 (1986): 301-20.

———. “Cultural Dimensions – Geert Hofstede.” https://www.geert-hofstede.com/national-culture.html.

Hofstede, Geert H., Gert Jan Hofstede, and Michael Minkov. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival. 3rd Ed. ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010.

Knowles, Malcolm S., Elwood F. Holton, and Richard A. Swanson. The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development. Eighth edition. ed. London ; New York: Routledge, 2015.

Law, Eric H. F. The Wolf Shall Dwell with the Lamb: A Spirituality for Leadership in a Multicultural Community. St. Louis: Chalice Press, 1993.

Lingenfelter, Judith E., and Sherwood G. Lingenfelter. Teaching Cross-Culturally: An Incarnational Model for Learning and Teaching. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2003.

Liu, Ngar-Fun, and William Littlewood. “Why Do Many Students Appear Reluctant to Participate in Classroom Learning Discourse?”. System 25, no. 3 (1997): 371-84.

Merriam, Sharan B. “Adult Learning Theory for the Twenty-First Century.” New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 2008, no. 119 (2008): 93-98.

———. Non-Western Perspectives on Learning and Knowing. Malabar: Krieger, 2007.

Nguyen, van Thanh. “Luke’s Point of View of the Gentile Mission: The Test Case of Acts 11:1-18.” Journal of Biblical and Pneumatological Research 3 (2011): 85-98.

Partners, Global Learning. “Principle-Driven.” Global Learning Partners, https://www.globallearningpartners.com/about-us/our-approach/.

Phuong-Mai, Nguyen, Cees Terlouw, and Albert Pilot. “Cooperative Learning Vs Confucian Heritage Culture’s Collectivism: Confrontation to Reveal Some Cultural Conflicts and Mismatch.” Asia Europe Journal 3, no. 3 (2005): 403-19.

Plueddemann, James. “An Introduction to Cross-Cultural Teaching and Learning.” http://www.jafriedrich.de/pdf/Introduction%20to%20Cross-Cultural%20Teaching%20and%20Learning.pdf.

Signorini, Paola, Rolf Wiesemes, and Roger Murphy. “Developing Alternative Frameworks for Exploring Intercultural Learning: A Critique of Hofstede’s Cultural Difference Model.” Teaching in Higher Education 14, no. 3 (2009): 253-64.

Tight, Malcolm. Key Concepts in Adult Education and Training. London: Routledge, 2002.

Uccellani, Val, and Anouk Janssens-Bevernage. “6 Core Principles, Virtually!”: Global Learning Partners, 2013.

Vella, Jane. “Global Learning Partners.” http://www.globallearningpartners.com/index.php.

Vella, Jane Kathryn. Learning to Listen, Learning to Teach: The Power of Dialogue in Educating Adults. Rev. ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2002.

Whitehead, Jo. “Towards a Practical Theology of Whole-Person Learning.” Journal of Adult Theological Education 11, no. 1 (05// 2014): 61-73.

Woodward, Marsha. “Demystifying Discipleship.” Mission Frontiers, no. 3 (2013): 21-24.

[1] These two are, having a high Power Distance Index and a high Uncertainty Avoidance Index.

[2] The name is significant as it points to the crux of the model, a two-way learning between teacher and learners (and also between learners and fellow-learners). Jane Kathryn Vella, Learning to Listen, Learning to Teach: The Power of Dialogue in Educating Adults, Rev. ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2002). Earle Bowen and Dorothy Bowen, “Contextualizing Teaching Methods in Africa,” Evangelical Missions Quarterly 25, no. 3 (1989); ibid.Earle Bowen and Dorothy Bowen, “Contextualizing Teaching Methods in Africa,” Evangelical Missions Quarterly 25, no. 3 (1989); ibid.Earle Bowen and Dorothy Bowen, “Contextualizing Teaching Methods in Africa,” Evangelical Missions Quarterly 25, no. 3 (1989); ibid.In 2016, the masthead of Vella’s website read, “The means is dialogue, the end is learning, the purpose is peace.” Jane Vella, “Global Learning Partners,” http://www.globallearningpartners.com/index.php. She also referred to this in her interview, highlighting her passion to be an ambassador of God, bringing Jesus’ peace through mutual learning.

[3] Val Uccellani and Anouk Janssens-Bevernage, Oct 11, 2013, https://www.globallearningpartners.com/blog/6-core-principles-virtually/. Through the rest of this article, the principles are referred to by their number and a shortened form of the principle.

[4] See chapters three to fourteen. Vella, Learning to Listen, Learning to Teach: The Power of Dialogue in Educating Adults.

[5] References and descriptions to the National Cultural Dimensions in the following pages are taken from Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov, Cultures and Organizations.

[6] Through this paper, descriptions of the six Dimensions of National Culture are based on those found in Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov, Cultures and Organizations.

[7] Stephen Brookfield, “Understanding and Facilitating Moral Learning in Adults,” Journal of Moral Education Vol. 27, no. 3 (1998): 4.

[8] One student is invited by the teacher to share their thoughts on the topic being discussed or to answer the question. They can choose to speak or not to speak. If they choose not speak, they say, ‘pass’. Whether they speak or not, they then invite one other person in the room to share. This continues until all have been invited to share. Eric H. F. Law, The Wolf Shall Dwell with the Lamb: A Spirituality for Leadership in a Multicultural Community (St. Louis: Chalice Press, 1993).

[9] See chapter ten. Ibid., 89-97.

[10] Definition accessed from https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/hidden_curriculum

[11] Malcolm S. Knowles, Elwood F. Holton, and Richard A. Swanson, The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development, Eighth edition. ed. (London ; New York: Routledge, 2015), 288.

[12] Law, The Wolf Shall Dwell with the Lamb: A Spirituality for Leadership in a Multicultural Community, 93.

[13] Jane Vella, interview by Susan Chapman, July 5 and July 7, 2016.

[14] See the similar comment at footnote 24.

[15] Jane Vella, interview by Susan Chapman, July 5 and July 7, 2016.

[16] Jane Vella, interview by Susan Chapman, July 5 and July 7, 2016. “While these twelve principles and practices are familiar, my own particular interpretation of each one and the unique applications demonstrated in the stories are a function of my own personal experience and reflection.” Vella, Learning to Listen, Learning to Teach: The Power of Dialogue in Educating Adults, xviii.

[17] Ibid., xvii.

[18] This was observed and noted within the Chinese mainland context. It is a point to remember in regards to Dialogue Education in cross-cultural settings. Peter Moore, interview by Susan Chapman, July 6, 2016.

[19] Regarding the differences themselves: “These can be due to different social positions of teachers and students in the two societies, to differences in the relevance of the curriculum for the two societies, to differences in profiles of cognitive abilities between the populations of the two societies, or to differences in expected teacher/student and student/student interaction.” Geert Hofstede, “Cultural Differences in Teaching and Learning,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 10, no. 3 (1986).

[20] Judith E. Lingenfelter and Sherwood G. Lingenfelter, Teaching Cross-Culturally: An Incarnational Model for Learning and Teaching (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2003), 52.

This is submitted by Susan Chapman of OMF International. OMF International is a Missio Nexus member. Member organizations can provide content to the Missio Nexus website. See how by clicking here.

Responses